The Grand Hotel That Might Have Been

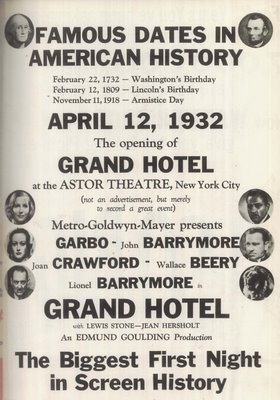

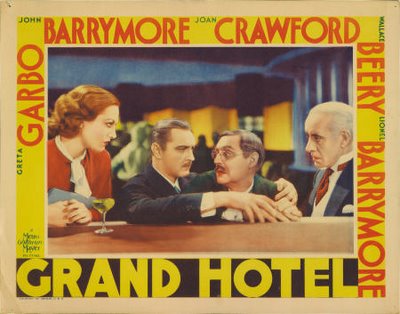

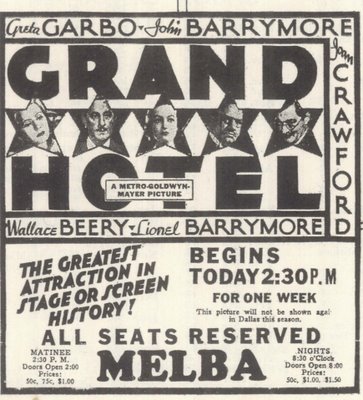

The Grand Hotel That Might Have BeenCasting what-ifs are a real waste of time in most cases, but one I would indulge concerns the legendary all-star Grand Hotel and the movie that might have been had MGM gone with their initial choices. Good as the finished product is, I can’t help wishing they’d stuck with the line-up as announced (if tentatively) in early trade mentions. There was a lot of interest in this property growing out of the play it was based on, and by December 1931, columnists were speculating on who might fill roles familiar from the stage version. The Hollywood Reporter posted a tentative line-up that month. Clark Gable, Buster Keaton, Jimmy Durante, and George E. Stone suggested something along comedic lines. Was Grand Hotel played more for laughs in its legit presentation? As late as December 28, Gable was "unofficially" tabbed for the project, even as shooting was to start in less than a week. Then there was John Gilbert, who’d eventually be replaced by John Barrymore. How close were these players to roles that would surely have changed the course of their careers, and in the case of Gilbert and Keaton, might possibly save them? What would it have been like to covet a part in a sure-fire major hit --- come so close to the realization of your desire --- then have it snatched away only days before production? If nothing else, the saga of Grand Hotel demonstrates just how capricious casting decisions could be, and how easily one missed (or gained) opportunity could hasten (or impede) a star’s momentum. A single Grand Hotel was worth a dozen ordinary vehicles. No studio (even Metro) was good for more than one or two such specials in any given year. You could coast a long time on a picture big as this …

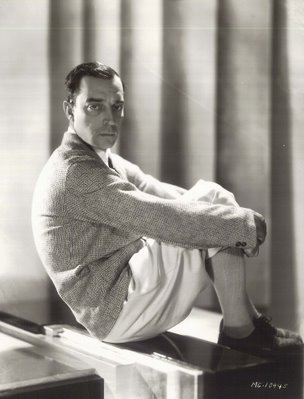

John Gilbert had cruised on the fabulous success of The Big Parade and other silent favorites, until sound closed the book on his stardom. The lucrative contract he’d signed with Loew’s chairman Nicholas Schenck guaranteed three years of top money and starring berths at MGM, but Schenck never dreamed Jack’s audience would abandon him so cruelly and suddenly. Animus on Louis Mayer’s part foreclosed serious efforts to rehabilitate a faltering image, and by 1930, Gilbert was declared washed up. One great picture might have saved him. There was nothing wrong with his appearance, as the overuse of alcohol had not yet made those inroads, but how could performances in things like West Of Broadway and A Gentleman’s Fate seem anything other than dispirited? There were only eight months to go on Gilbert’s contract in December 1931, and time was running out on a comeback, if not the actor’s health. He’d suffered with insomnia, bleeding stomach ulcers, and alcoholism that had progressed to a point where one drink made him deathly sick. It was understood early on that Grand Hotel would star John Gilbert, but that was when Metro first invested in the play, and before his last four pictures tanked. Though it too lost money, The Phantom Of Paris (shown here) was actually a major improvement upon previous films, and reviews had not been so generous since Gilbert’s silent heyday. Phantom plays well yet, as demonstrated on frequent TCM broadcasts, and he’s relaxed and assured at all times. If there was a crisis of confidence, Gilbert had overcome it with this performance. Jack thought he had a friend in Irving Thalberg, and indeed, they enjoyed a congenial social relationship, having known each other since the early twenties, but Thalberg was first and always a company man, and playing bridge with him on Sunday was no guarantee he’d cast you on Monday. Jack would now beg for the opportunity to do Grand Hotel. He kidded of ideal casting as a dissolute baron and faded lover, but few laughed with him. Greta Garbo seems to have wanted Gilbert, but when the prospect of Barrymore was dangled before her, all bets were off and Jack was out. I’d read that disappointment over Grand Hotel ended the star’s friendship with Thalberg, but evidence suggests otherwise, for by June of 1932, Gilbert was starring in a story he’d written entitled Downstairs, perhaps consolation for missing Grand Hotel, and far and away his finest work in talkies. The truly crushing blow came with Red Dust, which had been definitely set for Gilbert until Clark Gable’s ascent dictated otherwise. As this one didn’t go into production until August 1932, it did, in any case, miss the expiration date of Gilbert’s contract (July 31). If there was a rupture in the Gilbert/Thalberg relationship, this is probably where it occurred, and yet they were photographed together as late as November of that same year, as shown here (that’s Gilbert and new wife Virginia Bruce in a foursome with Norma Shearer and Thalberg).

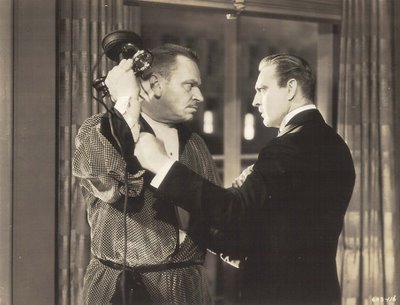

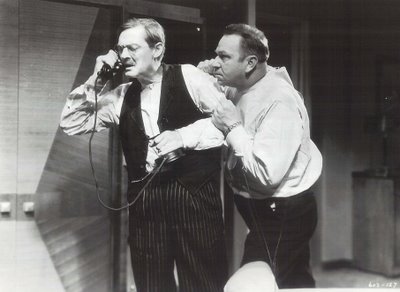

Clark Gable was actually considered for the Wallace Beery part, less surprising when you consider the brutish roles he’d essayed over the past year when the caveman image was taking shape. A Free Soul suggests Gable would have been ideal in Beery's part. No doubt he’d have made explicit what was merely implied by the relationship between Beery and Joan Crawford in Grand Hotel as we know it. The tension between he and Gilbert over Crawford (or perhaps even Garbo!) would have created sparks altogether missing from the more or less placid conflict played out by Barrymore and Beery. Columnist Elizabeth Yeaman posted the news on December 28, 1931 that Gable was "unofficially" set for the film, while Jimmy Starr would announce (within ten days) China Seas as the actor’s next starring role (though it would be three years before that one came to fruition). By January 13, Gable was definitely booked for Strange Interlude with Norma Shearer, which was filmed that Spring. Grand Hotel would have been a great role for the rough-edged, early Gable. Imagine that hotel room confrontation between he and Gilbert. The talkie’s newest romantic idol bashing in the head of a discarded silent lover --- and with a telephone receiver. Talk about a merger of art with life! Too bad we missed out on it. The demand for Gable was so great that to use him in an all-star feature might have been considered wasteful, and yet he’d be on hand a year later for Night Flight, with its similarly loaded marquee. His screen character would begin to soften after Red Dust (released October 1932), and the hard exterior would receive further massaging in musicals (Dancing Lady), reformation stories (Hold Your Man), and finally, romance comedy (It Happened One Night). Code artisans and studio image-makers chiseled away at Gable the Love Menace and found a lovable scamp underneath; safely (and reliably) marketable over the long haul, but with much of the edge gone forever. Audiences would forget thuggish, almost simian qualities of a pre-code beginner. When Robert Youngson included a particularly nasty clip from Night Nurse in his 1955 Warners compilation short, When The Talkies Were Young, viewers were startled to see their beloved (and by now firmly establishment) icon dressed up in storm trooper-ish chauffeur’s uniform and roughing up Barbara Stanwyck. The elapse of so many years, and a virtual disappearance of the films themselves, erased memories of Gable the primitive. Had he been given Grand Hotel, probably the most noted of all early-30’s MGM features, they might better have remembered this star in his formative period.

Would Buster Keaton have been spared the fate of Educational and Columbia two-reelers had he played Otto Kringelin (Lionel Barrymore’s eventual part) in Grand Hotel? To the end of his life, the comedian maintained he’d have done an efficient job of it, and if you look at Buster’s 1954 dramatic debut in The Awakening, an episode of Douglas Fairbanks Jr’s anthology series, there’s no doubt he was equal to the task of serious emoting. Grand Hotel director Edmund Goulding fired the idea in Keaton when he sent for him in late 1931. I make it a rule to become very serious about the fourth reel or so. That is to make absolutely sure that the audience will really care about what happens to me in the rest of the picture, said the comedian in his 1960 memoir, My Wonderful World Of Slapstick. Sounds like inspired off-casting for a star long dissatisfied with lousy assignments he’d been getting. The only good thing about Sidewalks Of New York and Parlor, Bedroom, and Bath were the profits they were earning. I was sure I could handle such a serious part --- but was the departure so radical? Lionel Barrymore's Kringelin evokes Buster at times (I would have played the part differently. I do not say better, mind you, just differently, said Keaton). Kringelin is the only major character in Grand Hotel that allows for comedy, and Buster could easily have woven some of that into the drama (his timid professor in Speak Easily, shown here, suggests Kringelin, in looks if not manner). Goulding’s strong direction and the challenge of work with major talent would no doubt have restored assurance Keaton had lost after those forced marches through poor vehicles. It would appear he lost the role when just cast John Barrymore insisted on brother Lionel as Kringelin. Disappointment over this may have been a major factor in exacerbating Buster’s drinking problem, for now there was only the prospect of a revised contract (for but a single year and with terms unfavorable to him) along with an increasingly prominent co-star (Jimmy Durante), whose star was rising even as Keaton’s fell. While Grand Hotel triumphed in general release, Buster was fast headed toward career crisis, and no one was surprised when the studio ax fell on February 2, 1933. Whatever future he might have had as a character actor (make that serio-comic star), similar indeed to what Lionel Barrymore enjoyed up to his death in 1954, was now lost to Keaton.

Keaton's absorption with Grand Hotel would continue. An idea for a "travesty" was presented to a polite, but indifferent Thalberg (Aside from Norma Shearer, his wife, I think I was his favorite MGM star, said Buster in later years, but wasn’t this merely an echo of John Gilbert’s hopeful supposition?). Keaton’s lampoon would utilize the standing hotel set and a cast of comedians sending up histrionics from the lately released blockbuster, but his framework for this farce suggested Buster himself had become another Metro pod person. He’d finally play Kringelin, but this time with life-threatening hiccups. Laurel and Hardy would be competing collar-button manufacturers. Polly Moran (in the Crawford role) was penciled in as the object of Hardy’s would-be seduction. As if to confirm whatever doubts one might have about his creative judgement, Keaton proposed Jimmy Durante for the John Barrymore role, with Marie Dressler as a strident Garbo substitute. The idea went nowhere, though the comedian would add a postscript decades later when preparing My Wonderful World Of Slapstick. It seems Thalberg did call back, but only after Buster had been sacked from MGM. Grand Mills Hotel was a go if Keaton was willing. Everything might have been different if I had gone back, but was the invitation actually extended? There’s reason to believe it wasn’t, but perhaps Buster needed something to cling to, even if it was the misguided notion that it was he who rejected Metro this time, and that his million-dollar concept was one they bungled.