The Bogarts Are Frisco-Bound

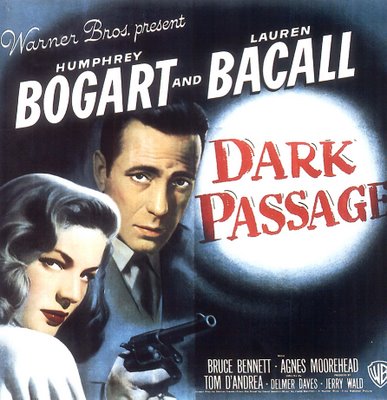

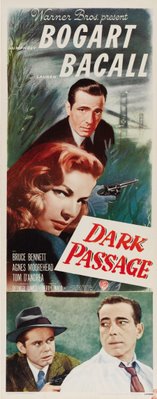

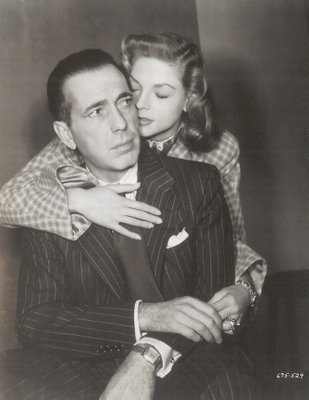

There’s something anti-Howard Hawks about the way Delmer Daves directs Dark Passage. No longer is Humphrey Bogart hit on by all the beautiful girls, nor does he get the last word (or punch) with this new line of antagonists. Were San Franciscans as hateful and petty as this in 1947? Bogart’s Vincent Parry constantly runs up against people who talk too much, speak out of turn, and ask too many nosey questions. Bus station attendants are surly and quarrelsome, the guy behind a lunch counter shoots off his mouth and puts Bogie on the spot with a suspicious cop. None of this is very accommodating to the Bogart/Bacall romance and action formula established by Hawks with To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep. Suddenly, the glamour couple who’d always quipped above the fray was confronted with the harsher realities of post-war noir, and Bacall in particular seems lost. Besieged with commonplace aggravations normally visited upon noir brethren like Steve Brodie, Dana Andrews, or Farley Granger, the Bogart’s former luck in prevailing over various Hawksian opponents seems to have run aground, and there’s only Dark Passage’s romantic fade to bail them out and restore our confidence. Until then, we’re surprised to see Bogart in born loser posture subject to frame-ups and blackmail. He’s actor enough to convey everyman despair, but his wife comes off ordinary and minimally competent now that Hawks’ protective aura has been removed. It’s this level of uncertainty that makes Dark Passage compelling for me. Bogart’s post-surgical walk up endless stairs stays in the memory, as does the face procedure itself (I can make you look like a bulldog, or a monkey). Character vignettes abound. People like Tom D’Andrea, Bruce Bennett, Douglas Kennedy, and Clifton Young have nice turns in the spotlight, and Bogart’s generous in throwing scenes their way. I’d not forgotten Young’s sneering villainy (he’s a would-be blackmailer driving the jalopy) since seeing Dark Passage the first time at fourteen. He actually reminded me then of eighth-graders at my school. Was that déjà vu that came of having seen him in Our Gang comedies wherein he played a character named "Bonedust"? I was astonished to learn that the kid who brought the Minstrel and Blackface Joke-Book to the classroom in School’s Out was the selfsame Clifton (then Bobby) Young who would later bedevil Bogart. I wouldn't have expected him to turn up in a Republic Trucolor western from the (approximate) same period either, but there he is menacing Roy Rogers in Bells Of Coronado. There were multiple appearances in Joe McDoakes comedies as well. Turns out Young came to a tragic end when a cigarette caught his hotel bed on fire in 1951. Amazing how puzzle pieces come together with the help of imdb.

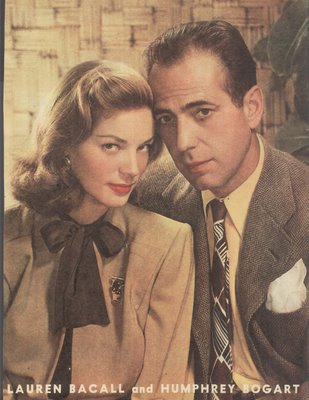

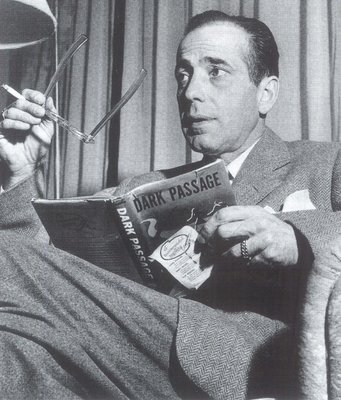

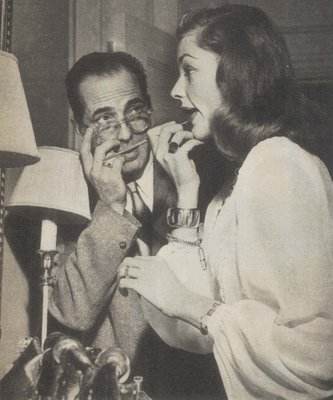

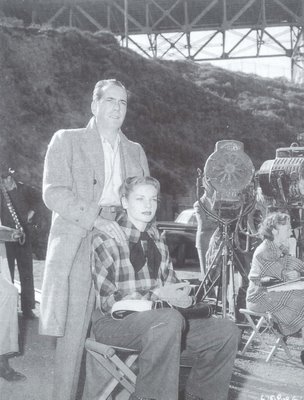

Bogart’s hair was starting to fall out when he made Dark Passage. He had to take hormone injections to alleviate it. Bad nutrition and those twin excesses of alcohol and tobacco were blamed, but the star gave up neither. Three of the pictures just previous, Conflict, The Big Sleep, and The Two Mrs. Carrolls, had been shot, then shelved, for as much as two years prior to their release, so to a lot of his fans, Bogart suddenly looked older in Dark Passage. Most of the picture was shot on location in San Francisco, and as the Bogart’s off-screen relationship was now legally sanctioned by marriage, they were joined in their hotel suite by press profilers anxious to observe, and photograph, their domestic habits. Bogart was riding higher at this point than ever before. Everything he did at Warners made money. Even one he deplored, Conflict, brought back a hatful of profit (two million, which equaled The Big Sleep!). The new contract (67 pages long) called for a single picture each year at $200,000 per, plus one outside he’d be permitted per annum. Monies earned in 1946 totaled $467,361. No wonder folks assumed Bogart left his family rich when he died in 1957, but according to later Bacall interviews, that wasn’t necessarily the case. Well, after all, would Betty have done Shock Treatment had she been in the chips? Overhead then was as now. In Hollywood, it could be ruinous. Bogart had actually wanted to do Dark Passage. The source novel by David Goodis was a downbeat thing about dead end lives, and the central conceit of hiding the star’s face for the entire first half was tricky business for customers expecting to look at the visage they’d paid to see. Was Bogart doubled during all those just off camera and shadow shots? I think not, and for two reasons. One are the arms. You see those a lot when he’s reaching for blankets, taking straws from Bacall, and whatnot. They're Bogie’s alright. This was one hirsute guy, and both hands and arms are distinctive. Plus, I don’t think he’d have left his wife to play against a stand-in. He would have wanted to protect her, and besides, Bacall needed all the help she could get at this stage in her career. She’d acknowledge later the at-home acting lessons he gave her. Remember the scene in The Big Sleep where she’s cutting his ropes? Never was Bogart so solicitous of her. Much of that dialogue is ad-libbed. You can tell he’s afraid she’ll hurt herself. Watch your fingers. Don’t cut toward your hand. That must have been an anxious scene for Bogart to get through.

A major Bogart career loss came with the death of producer Mark Hellinger. They’d planned to get together on those outside pictures the actor envisioned when he signed the new pact with Warners. Bogart admired writers, and Hellinger was a seasoned one. He’d worked on newspapers and knew the rhythm of the mean streets, coming to WB in the late thirties and earning Bogart’s respect by going to the mat with senior producer Hal Wallis, for whom he’d begun as an associate. Hellinger was also a world class drinker and raconteur, all of which further endeared him to the star. His talent lay in judging and packaging talent. Recently back from wartime service, Hellinger demonstrated an unerring eye for new kinds of crime stories that seemed all but revolutionary to post-war Hollywood. The Killers, Brute Force, and Naked City were essentially Warner thrillers taken to a new level of realism. Having produced several of the better Bogarts for Warners, They Drive By Night and High Sierra among them, he would now team with the actor for a series of independent productions. David O. Selznick came on board with partial financing. Bogart would also invest. Various banks agreed to furnish the balance. All these negotiations took place around the time of Dark Passage. Then Mark Hellinger collapsed with one of those heart attacks you get polishing off two quarts a day, and with him went the deals. I’ve often considered what direction Bogart’s future might have taken had the producer lived. We’d have likely had films of Naked City and Brute Force quality, rather than Tokyo Joe, Sirocco, and the rest we got. With Hellinger’s death, and Treasure Of The Sierra Madre and Key Largo behind him, Bogart went into a bad patch producing for himself with assist from substitute Warners veteran, Robert Lord, who had nowhere near Hellinger’s capability (only one of the Santanas, In A Lonely Place, was really outstanding). There were but two more associations with John Huston, and none with Howard Hawks. Bogart was largely adrift in the fifties without collaborators worthy of him. Single projects for major directors like Billy Wilder and William Wyler provided little on which to build the sort of creative foundation he’d developed with Huston and Hawks. A Bogart/Hellinger teaming might have led to a second wave of classics --- imagine the series of noirs these two might have produced. Fate deprived us of quite a banquet here.

You could say Dark Passage was the last of the vintage Bogart pictures. Treasure Of The Sierra Madre would point more toward character leads, and Key Largo was somehow loftier than lighter confections Huston had previously directed (Across the Pacific, which I prefer). No more convicts nor dwellings in moral twilight for Bogart. Chain Lightning would find him test-piloting in skies soon overpopulated with more conventional leading men, but what did Bogart have in common with William Holden, James Stewart, or John Wayne, and which branch of the service would be so remiss as to send a man of his years aloft? Of all his starring Warner vehicles, Chain Lightning may be the one least mentioned today. I’ve always liked The Enforcer, but he’s the establishment figure crusading against crime here, and would continue doing so in the following year’s (1952) Deadline USA. There was now no question as to which side of the law Bogart was on. To see him back in (escaped) prisoner attire was all the more surprising in late-in-the-day The Desperate Hours. These were my youthful introductions to Bogart, for they were sold among syndication packages otherwise salted with color titles to satisfy broadcaster’s demand for something other than stale pre-48 groups. Dark Passage came my way by virtue of a backwoods station from Asheville we could barely pick up that probably never heard of color TV. Remember the hell of watching movies on local channels? They’d mutilate features to cram them into ninety-minute time frames, then spend a third of that on commercials and "Dialing For Dollars" nonsense. It’s a wonder any of us developed an interest in this stuff, let alone maintained it through years of sustained abuse and neglect. I remember one UHF outpost out of Charlotte that simply switched off Treasure Of the Sierra Madre with ten minutes left to go, just so they could move on to an episode of Davey and Goliath. Basking as we are in this era of TCM and DVD privilege, we forget how austere conditions once were. Most of us could fill a column with horror stories of wretched reception, relentless interruption, and jabbering hosts. Hey, that sounds like a like a ripe subject for a future Greenbriar posting…