Region 2 Round-Up --- Part Two

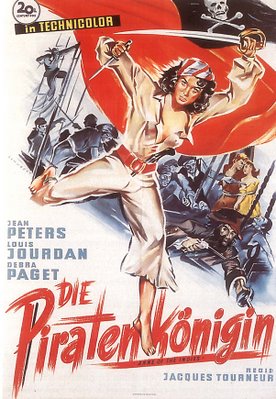

I knew Anne Of the Indies was in trouble when she had captives walking a plank (and falling to their deaths) during the opening reel of this most enjoyable 20th Fox pirate adventure directed by Jacques Tourneur. Jean Peters would either have to die at the end or be "brought to justice." Distaff pirates require a suspension of disbelief beyond even that customary with pictures of this type, and you could say Peters is no more credible than Maureen O’Hara, Hillary Brooke, Geena Davis, or other members of that rarefied sorority. Very much like The Black Swan, only better, Anne Of the Indies got on and off in less than 80 minutes (at least by the speeded up clock of Region 2 PAL conversion), and took its place near the top of my favorite Tourneurs list (along with his three Lewtons, Canyon Passage, Out Of The Past, Stars In My Crown, and Curse Of The Demon). Offbeat touches include a pirate’s wrestling match with a bear, affording us a glimpse of what that legendarily deleted scene from The Wolf Man might have looked like. Fetching Jean Peters seems at all times a high school girl playing at piracy, but who’d want her muscled-up and butchy, as modern-day agenda loyalists would no doubt enact this role? Louis Jourdon’s fragility suggests he might be dominated by such an opponent, though the choice he’s obliged to make between Jean Peters and Debra Paget would be an enviable, if ultimately frustrating, one. Peters makes good on the promise of duel scenes pictured in ads and posters (a European one shown here). I watched the sword action closely and detected little in the way of doubling. Maybe this actress embraced those obligatory fencing lessons contract players had to take whenever they signed on with big studios. She must surely have considered Anne Of the Indies one of her more rewarding parts, though I can’t recall having seen a published interview with Jean after she retired in 1955. Anybody know of one? Fox memos of the time recognized Anne Of The Indies’ appeal to worldwide audiences. Zanuck noted domestic rentals ($1.2 million) that fell short of the negative cost ($1.4), but cited outstanding foreign receipts ($1.5 million) that put the picture into a modest profit of $111,000. He warned of pictures too dependent upon US returns, such as I’d Climb The Highest Mountain, Wait Till The Sun Shines, Nellie, and other Americana subjects, having hard climbs toward breaking even without elements attractive to worldwide markets. Judging by deluxe presentation on the import DVD, Anne Of The Indies has maintained its stature among French viewers (Tourneur’s considerable auteurist rep helps). We seem to have forgotten all about this show stateside. Fox never released it in any home video format, and I can’t recall seeing Anne Of The Indies on AMC or the company’s Movie Channel (for that matter, I never even encountered a decent 16mm print in color). With everyone so enraptured by pirates of the Caribbean, I’m surprised Fox hasn’t at least released Anne as a bare-bones DVD. Ordering it HERE may indeed be our only recourse for some time to come.

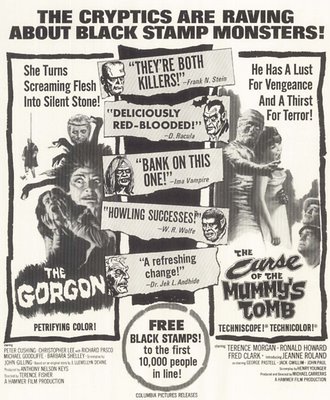

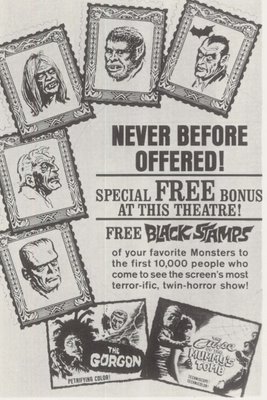

Horror/sci-fi combos were that much tougher to sell by the mid-sixties when Columbia released another two Hammer chillers stateside. Memories of block-round lines for Curse Of Frankenstein in 1957 and Horror Of Dracula in 1958 still inspired confidence that perhaps lightning could strike just once more, but these selfsame monsters were now running loose all over television, and the novelty of watching them spill a little more blood in theatres had long since past. Worse still, fans were beginning to access color horror movies on their TV’s, even some of the early (and better) Hammers. Increasingly silly campaigns were adjudged the answer, as shown here with "Black Stamp" giveaways to accompany the combo of Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb and The Gorgon (she had a face only a Mummy could love --- was MAD magazine now composing ad copy?). The stamps reminded me of something included with those nauseating sheets of bubble gum that would snap in two when you opened the pack and proved near impossible to chew (lest you were willing to sacrifice what was left of your baby teeth doing so). The fact stamps were available to the first 10,000 people in line reflected foolhardy optimism on Columbia’s part unlikely to be fulfilled at any venue running these two. Our beloved Liberty played the combo (first Saturday after school let out in June 1965), but nixed on Black Stamps, possibly in avoidance of giving them away clear through to 1972 as means of stock dosposal. How refreshing then, to find Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb and The Gorgon departing well from antic salesmanship Columbia inflicted upon them, both being literate and effective chillers. I eagerly await The Gorgon’s arrival on DVD (and hope it’ll be like the stunner broadcast on Monsters HD last year), but in a meantime, we have Curse Of the Mummy’s Tomb just out on Region 2 from the UK. Some aver Hammer reached beyond grasp here, but I admire this ambitious storyline of brother pharaohs' sustained rivalry through centuries. Why not direct as though you were David Lean and this was Lawrence Of Arabia? --- and indeed, Michael Carreras does. Characters are unpredictable, none are sympathetic, and all benefit from seasoned British thesps portraying them. I could wish this mummy weren't encased in a loose-fitting union suit (with all but a buttoned flap on its rear), but Hammer enjoyed not the luxuries of Jack Pierce make-up nor eight-hours necessary to apply it. We were impressed in 1965 by a generous helping of limb-lobbing, but why this emphasis upon hands being severed? Something to do with that ancient curse, as I realized during more recent screenings, but chances are you’ll opt for protective mittens, or at the least very long sleeves, after viewing Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb. By way of declining revenue, even Black Stamps weren’t enough to prevent tide going out on Hammer horrors. This Mummy drew but $218,000 in domestic rentals, significantly less than Columbia’s homegrown shockers. Straight Jacket had pulled $1.7 million. A sci-fi with more promotion backing it, First Men In The Moon, scored $887,000. Even a same-year Hammer they handled, Die! Die! My Darling, took nearly twice the Mummy’s haul with $400,000.

Merrill’s Marauders was an even then (1962) old-fashioned war movie lacking the sharper edge one expects from renegade director Samuel Fuller. Could Jack Warner have dictated they stick closer to the Objective, Burma model (even to the extent of reusing much of its score)? Credited co-writer and Warner son-in-law Milton Sperling might have subverted Fuller’s customarily hard-bitten approach to combat subjects. This was, after all, a bigger budget show, and off-putting realism of a Steel Helmet or Fixed Bayonet sort might prove too unsettling for mainstream audiences Warner was courting. Still, this is a more than satisfying update on Burma, and what a welcome sight that wide screen was after years of having it available (if at all) in cropped versions. Sad that Jeff Chandler didn’t get beyond this final performance, dead at only 42 after what I’ve read was a botched operation. Contract players Ty Hardin, Will Hutchins, and Peter Brown were coming to the end of Warner tenures here. This may be their best big-screen work. Hardin is particularly good as second-in-command. Hutchins told us at an autograph show of being flown to the Philippines location one-way, and when scenes were completed, being cut loose without return passage home. Will was on his own. Such was life in WB stables. Merrill’s Marauders represents a last stand for traditional war movies before elephantine excesses (The Longest Day, Battle Of The Bulge) and espionage exotics (Operation Crossbow, The Guns Of Navarone) took hold. If you watched it beside 1956's Attack, you’d think Robert Aldrich's picture came six years later rather than earlier. Were it not for color and scope, Merrill’s Marauders would fit nicely with Air Force, Destination Tokyo, and of course, Objective, Burma, for it would seem to have been made within months of these. Milton Sperling’s United States Pictures banner had flown over a number of Warner recyclings. Distant Drums (1953) was another remake of Objective, Burma he’d produced, this one set in the Everglades. Ownership of Merrill’s Marauders did at least remain with Warners. Most of the other United States negatives passed through various hands and are presently owned by Richard Feiner and Company. Based on the lackluster quality of those released so far on DVD (The Enforcer, Pursued, The Court-Martial Of Billy Mitchell, etc.), I’d say all the elements could use some upgrading.

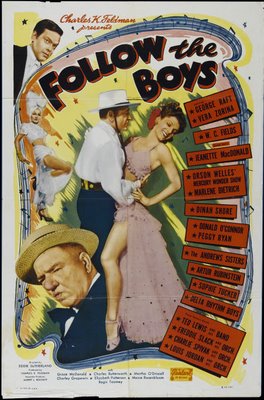

Process screens are rife in Follow The Boys, Universal’s 1944 contribution to the wartime wave of all-star musical revues. We see Donald O’Connor and Peggy Ryan running out to greet what looks to be thousands of GI’s at an outdoor camp stage, only to find themselves cut away to a studio mock-up of the location for their number. What a disappointment Universal didn’t capture that act as it played to the recruits, though it is nice to finally have something of this team on DVD at last. Were it not for Marlene Dietrich’s limited participation, it’s unlikely Follow The Boys would have turned up at all. As it is, we get this as one of eighteen Dietrich features contained in a monster box set recently released in the UK (other selections include rarities Desire, Angel, and the Von Sternberg fave, Shanghai Express). One disturbance here is the running time, a mere 106 minutes. The original ran 122, and though I saw it before at that length, I couldn’t detect anything missing this time. Universal topliners passed on Follow The Boys, thus no Abbott and Costello or Deanna Durbin. We do glimpse Nigel Bruce among a crowd, but no Rathbone (understandable as he was contracted to MGM, and did his Universal Holmes series on loan-outs). Stars like Gloria Jean, Maria Montez, and Evelyn Ankers are shown in pans across rows of silent onlookers at a pep meeting conducted by leading man George Raft. The Lon Chaney shown here (seated behind Sophie Tucker) says not one word and has but this single shot to represent him in the whole of the film. Do also note Orson Welles seated with similarly mute Noah Beery, Jr., with Turhan Bey behind. Welles is a more vocal participant, and gets in his magician act with Dietrich in support. Interesting to see Orson comparatively thin and robust, a dashing figure in top hat and tails, his sleight-of-hand neutralized somewhat by clunky special effects revealing studio artifice behind his "magic." Highlights like this are interspersed with lackluster vaudeville. There’s even an extended dog act presided over by Charles Butterworth. The Andrews Sisters might be anticipated in any Universal show from this period, but again, their act is compromised by an uneasy blend of actual performance and soundstage recreation --- same for Jeannette MacDonald, though she has a nice number in a hospital tent which at least suggests the emotional bond shared by these performers and the servicemen they entertained. Near to the end W.C. Fields saunters into a post canteen to do his pool table routine for what would be the last time. It took Bill just two days to film, despite a schedule allowing for ten. Still, his pacing is slowed. Favored stooge Bill Wolfe walks through unmolested, as if The Great Man had simply forgotten he was there, while subdued laughter from the intercut "audience" is kept to a minimum, possibly on the theory that theatre-goers’ mirth would fill the void. One look at Fields' haggard appearance and you know why he couldn’t get insured for another feature. Still, his routine is what keeps Follow The Boys on radar for hardcore fans today, and if ever we get it released on Region 1, it’ll probably be as part of W.C. Fields --- Volume Three.