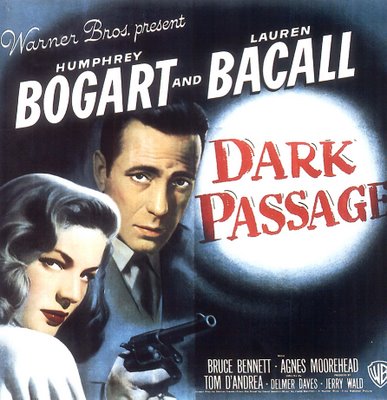

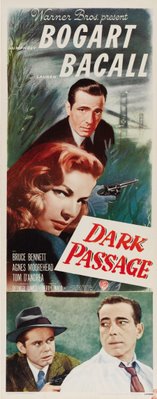

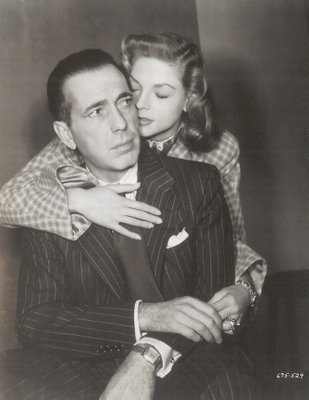

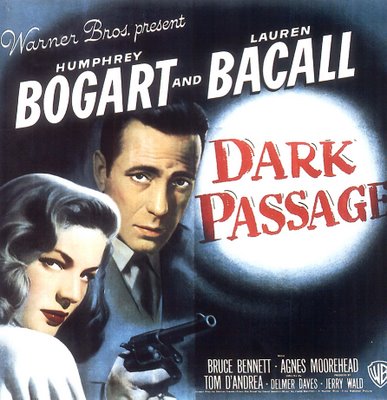

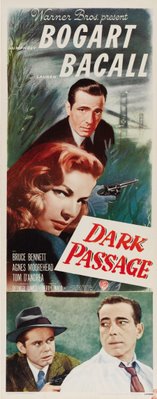

The Bogarts Are Frisco-BoundThere’s something anti-Howard Hawks about the way Delmer Daves directs Dark Passage. No longer is Humphrey Bogart hit on by all the beautiful girls, nor does he get the last word (or punch) with this new line of antagonists. Were San Franciscans as hateful and petty as this in 1947? Bogart’s Vincent Parry constantly runs up against people who talk too much, speak out of turn, and ask too many nosey questions. Bus station attendants are surly and quarrelsome, the guy behind a lunch counter shoots off his mouth and puts Bogie on the spot with a suspicious cop. None of this is very accommodating to the Bogart/Bacall romance and action formula established by Hawks with To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep. Suddenly, the glamour couple who’d always quipped above the fray was confronted with the harsher realities of post-war noir, and Bacall in particular seems lost. Besieged with commonplace aggravations normally visited upon noir brethren like Steve Brodie, Dana Andrews, or Farley Granger, the Bogart’s former luck in prevailing over various Hawksian opponents seems to have run aground, and there’s only Dark Passage’s romantic fade to bail them out and restore our confidence. Until then, we’re surprised to see Bogart in born loser posture subject to frame-ups and blackmail. He’s actor enough to convey everyman despair, but his wife comes off ordinary and minimally competent now that Hawks’ protective aura has been removed. It’s this level of uncertainty that makes Dark Passage compelling for me. Bogart’s post-surgical walk up endless stairs stays in the memory, as does the face procedure itself (I can make you look like a bulldog, or a monkey). Character vignettes abound. People like Tom D’Andrea, Bruce Bennett, Douglas Kennedy, and Clifton Young have nice turns in the spotlight, and Bogart’s generous in throwing scenes their way. I’d not forgotten Young’s sneering villainy (he’s a would-be blackmailer driving the jalopy) since seeing Dark Passage the first time at fourteen. He actually reminded me then of eighth-graders at my school. Was that déjà vu that came of having seen him in Our Gang comedies wherein he played a character named "Bonedust"? I was astonished to learn that the kid who brought the Minstrel and Blackface Joke-Book to the classroom in School’s Out was the selfsame Clifton (then Bobby) Young who would later bedevil Bogart. I wouldn't have expected him to turn up in a Republic Trucolor western from the (approximate) same period either, but there he is menacing Roy Rogers in Bells Of Coronado. There were multiple appearances in Joe McDoakes comedies as well. Turns out Young came to a tragic end when a cigarette caught his hotel bed on fire in 1951. Amazing how puzzle pieces come together with the help of imdb.

The Bogarts Are Frisco-BoundThere’s something anti-Howard Hawks about the way Delmer Daves directs Dark Passage. No longer is Humphrey Bogart hit on by all the beautiful girls, nor does he get the last word (or punch) with this new line of antagonists. Were San Franciscans as hateful and petty as this in 1947? Bogart’s Vincent Parry constantly runs up against people who talk too much, speak out of turn, and ask too many nosey questions. Bus station attendants are surly and quarrelsome, the guy behind a lunch counter shoots off his mouth and puts Bogie on the spot with a suspicious cop. None of this is very accommodating to the Bogart/Bacall romance and action formula established by Hawks with To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep. Suddenly, the glamour couple who’d always quipped above the fray was confronted with the harsher realities of post-war noir, and Bacall in particular seems lost. Besieged with commonplace aggravations normally visited upon noir brethren like Steve Brodie, Dana Andrews, or Farley Granger, the Bogart’s former luck in prevailing over various Hawksian opponents seems to have run aground, and there’s only Dark Passage’s romantic fade to bail them out and restore our confidence. Until then, we’re surprised to see Bogart in born loser posture subject to frame-ups and blackmail. He’s actor enough to convey everyman despair, but his wife comes off ordinary and minimally competent now that Hawks’ protective aura has been removed. It’s this level of uncertainty that makes Dark Passage compelling for me. Bogart’s post-surgical walk up endless stairs stays in the memory, as does the face procedure itself (I can make you look like a bulldog, or a monkey). Character vignettes abound. People like Tom D’Andrea, Bruce Bennett, Douglas Kennedy, and Clifton Young have nice turns in the spotlight, and Bogart’s generous in throwing scenes their way. I’d not forgotten Young’s sneering villainy (he’s a would-be blackmailer driving the jalopy) since seeing Dark Passage the first time at fourteen. He actually reminded me then of eighth-graders at my school. Was that déjà vu that came of having seen him in Our Gang comedies wherein he played a character named "Bonedust"? I was astonished to learn that the kid who brought the Minstrel and Blackface Joke-Book to the classroom in School’s Out was the selfsame Clifton (then Bobby) Young who would later bedevil Bogart. I wouldn't have expected him to turn up in a Republic Trucolor western from the (approximate) same period either, but there he is menacing Roy Rogers in Bells Of Coronado. There were multiple appearances in Joe McDoakes comedies as well. Turns out Young came to a tragic end when a cigarette caught his hotel bed on fire in 1951. Amazing how puzzle pieces come together with the help of imdb.

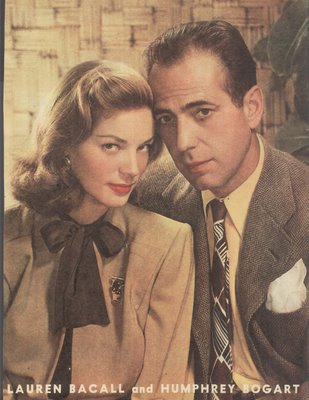

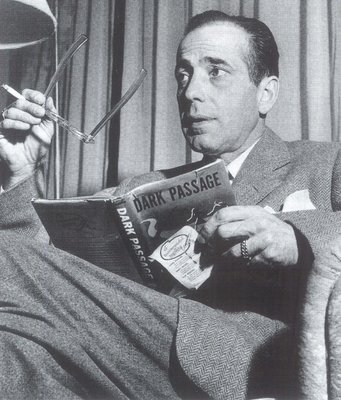

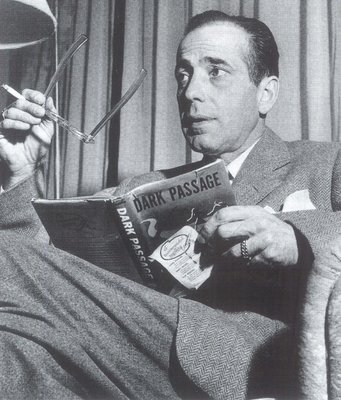

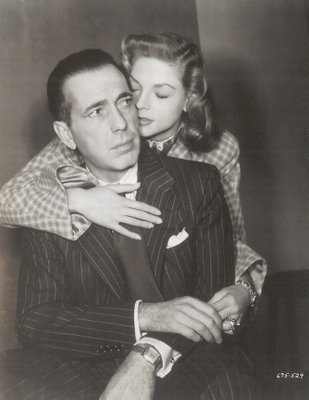

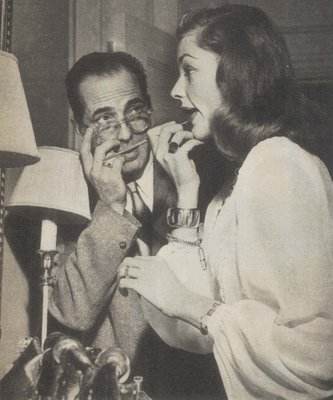

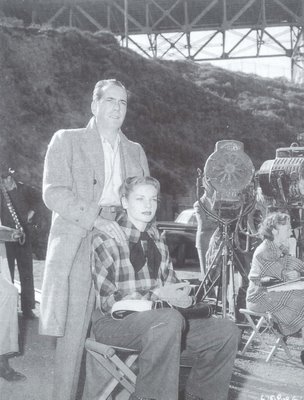

Bogart’s hair was starting to fall out when he made Dark Passage. He had to take hormone injections to alleviate it. Bad nutrition and those twin excesses of alcohol and tobacco were blamed, but the star gave up neither. Three of the pictures just previous, Conflict, The Big Sleep, and The Two Mrs. Carrolls, had been shot, then shelved, for as much as two years prior to their release, so to a lot of his fans, Bogart suddenly looked older in Dark Passage. Most of the picture was shot on location in San Francisco, and as the Bogart’s off-screen relationship was now legally sanctioned by marriage, they were joined in their hotel suite by press profilers anxious to observe, and photograph, their domestic habits. Bogart was riding higher at this point than ever before. Everything he did at Warners made money. Even one he deplored, Conflict, brought back a hatful of profit (two million, which equaled The Big Sleep!). The new contract (67 pages long) called for a single picture each year at $200,000 per, plus one outside he’d be permitted per annum. Monies earned in 1946 totaled $467,361. No wonder folks assumed Bogart left his family rich when he died in 1957, but according to later Bacall interviews, that wasn’t necessarily the case. Well, after all, would Betty have done Shock Treatment had she been in the chips? Overhead then was as now. In Hollywood, it could be ruinous. Bogart had actually wanted to do Dark Passage. The source novel by David Goodis was a downbeat thing about dead end lives, and the central conceit of hiding the star’s face for the entire first half was tricky business for customers expecting to look at the visage they’d paid to see. Was Bogart doubled during all those just off camera and shadow shots? I think not, and for two reasons. One are the arms. You see those a lot when he’s reaching for blankets, taking straws from Bacall, and whatnot. They're Bogie’s alright. This was one hirsute guy, and both hands and arms are distinctive. Plus, I don’t think he’d have left his wife to play against a stand-in. He would have wanted to protect her, and besides, Bacall needed all the help she could get at this stage in her career. She’d acknowledge later the at-home acting lessons he gave her. Remember the scene in The Big Sleep where she’s cutting his ropes? Never was Bogart so solicitous of her. Much of that dialogue is ad-libbed. You can tell he’s afraid she’ll hurt herself. Watch your fingers. Don’t cut toward your hand. That must have been an anxious scene for Bogart to get through.

Bogart’s hair was starting to fall out when he made Dark Passage. He had to take hormone injections to alleviate it. Bad nutrition and those twin excesses of alcohol and tobacco were blamed, but the star gave up neither. Three of the pictures just previous, Conflict, The Big Sleep, and The Two Mrs. Carrolls, had been shot, then shelved, for as much as two years prior to their release, so to a lot of his fans, Bogart suddenly looked older in Dark Passage. Most of the picture was shot on location in San Francisco, and as the Bogart’s off-screen relationship was now legally sanctioned by marriage, they were joined in their hotel suite by press profilers anxious to observe, and photograph, their domestic habits. Bogart was riding higher at this point than ever before. Everything he did at Warners made money. Even one he deplored, Conflict, brought back a hatful of profit (two million, which equaled The Big Sleep!). The new contract (67 pages long) called for a single picture each year at $200,000 per, plus one outside he’d be permitted per annum. Monies earned in 1946 totaled $467,361. No wonder folks assumed Bogart left his family rich when he died in 1957, but according to later Bacall interviews, that wasn’t necessarily the case. Well, after all, would Betty have done Shock Treatment had she been in the chips? Overhead then was as now. In Hollywood, it could be ruinous. Bogart had actually wanted to do Dark Passage. The source novel by David Goodis was a downbeat thing about dead end lives, and the central conceit of hiding the star’s face for the entire first half was tricky business for customers expecting to look at the visage they’d paid to see. Was Bogart doubled during all those just off camera and shadow shots? I think not, and for two reasons. One are the arms. You see those a lot when he’s reaching for blankets, taking straws from Bacall, and whatnot. They're Bogie’s alright. This was one hirsute guy, and both hands and arms are distinctive. Plus, I don’t think he’d have left his wife to play against a stand-in. He would have wanted to protect her, and besides, Bacall needed all the help she could get at this stage in her career. She’d acknowledge later the at-home acting lessons he gave her. Remember the scene in The Big Sleep where she’s cutting his ropes? Never was Bogart so solicitous of her. Much of that dialogue is ad-libbed. You can tell he’s afraid she’ll hurt herself. Watch your fingers. Don’t cut toward your hand. That must have been an anxious scene for Bogart to get through.

A major Bogart career loss came with the death of producer Mark Hellinger. They’d planned to get together on those outside pictures the actor envisioned when he signed the new pact with Warners. Bogart admired writers, and Hellinger was a seasoned one. He’d worked on newspapers and knew the rhythm of the mean streets, coming to WB in the late thirties and earning Bogart’s respect by going to the mat with senior producer Hal Wallis, for whom he’d begun as an associate. Hellinger was also a world class drinker and raconteur, all of which further endeared him to the star. His talent lay in judging and packaging talent. Recently back from wartime service, Hellinger demonstrated an unerring eye for new kinds of crime stories that seemed all but revolutionary to post-war Hollywood. The Killers, Brute Force, and Naked City were essentially Warner thrillers taken to a new level of realism. Having produced several of the better Bogarts for Warners, They Drive By Night and High Sierra among them, he would now team with the actor for a series of independent productions. David O. Selznick came on board with partial financing. Bogart would also invest. Various banks agreed to furnish the balance. All these negotiations took place around the time of Dark Passage. Then Mark Hellinger collapsed with one of those heart attacks you get polishing off two quarts a day, and with him went the deals. I’ve often considered what direction Bogart’s future might have taken had the producer lived. We’d have likely had films of Naked City and Brute Force quality, rather than Tokyo Joe, Sirocco, and the rest we got. With Hellinger’s death, and Treasure Of The Sierra Madre and Key Largo behind him, Bogart went into a bad patch producing for himself with assist from substitute Warners veteran, Robert Lord, who had nowhere near Hellinger’s capability (only one of the Santanas, In A Lonely Place, was really outstanding). There were but two more associations with John Huston, and none with Howard Hawks. Bogart was largely adrift in the fifties without collaborators worthy of him. Single projects for major directors like Billy Wilder and William Wyler provided little on which to build the sort of creative foundation he’d developed with Huston and Hawks. A Bogart/Hellinger teaming might have led to a second wave of classics --- imagine the series of noirs these two might have produced. Fate deprived us of quite a banquet here.

A major Bogart career loss came with the death of producer Mark Hellinger. They’d planned to get together on those outside pictures the actor envisioned when he signed the new pact with Warners. Bogart admired writers, and Hellinger was a seasoned one. He’d worked on newspapers and knew the rhythm of the mean streets, coming to WB in the late thirties and earning Bogart’s respect by going to the mat with senior producer Hal Wallis, for whom he’d begun as an associate. Hellinger was also a world class drinker and raconteur, all of which further endeared him to the star. His talent lay in judging and packaging talent. Recently back from wartime service, Hellinger demonstrated an unerring eye for new kinds of crime stories that seemed all but revolutionary to post-war Hollywood. The Killers, Brute Force, and Naked City were essentially Warner thrillers taken to a new level of realism. Having produced several of the better Bogarts for Warners, They Drive By Night and High Sierra among them, he would now team with the actor for a series of independent productions. David O. Selznick came on board with partial financing. Bogart would also invest. Various banks agreed to furnish the balance. All these negotiations took place around the time of Dark Passage. Then Mark Hellinger collapsed with one of those heart attacks you get polishing off two quarts a day, and with him went the deals. I’ve often considered what direction Bogart’s future might have taken had the producer lived. We’d have likely had films of Naked City and Brute Force quality, rather than Tokyo Joe, Sirocco, and the rest we got. With Hellinger’s death, and Treasure Of The Sierra Madre and Key Largo behind him, Bogart went into a bad patch producing for himself with assist from substitute Warners veteran, Robert Lord, who had nowhere near Hellinger’s capability (only one of the Santanas, In A Lonely Place, was really outstanding). There were but two more associations with John Huston, and none with Howard Hawks. Bogart was largely adrift in the fifties without collaborators worthy of him. Single projects for major directors like Billy Wilder and William Wyler provided little on which to build the sort of creative foundation he’d developed with Huston and Hawks. A Bogart/Hellinger teaming might have led to a second wave of classics --- imagine the series of noirs these two might have produced. Fate deprived us of quite a banquet here.

You could say Dark Passage was the last of the vintage Bogart pictures. Treasure Of The Sierra Madre would point more toward character leads, and Key Largo was somehow loftier than lighter confections Huston had previously directed (Across the Pacific, which I prefer). No more convicts nor dwellings in moral twilight for Bogart. Chain Lightning would find him test-piloting in skies soon overpopulated with more conventional leading men, but what did Bogart have in common with William Holden, James Stewart, or John Wayne, and which branch of the service would be so remiss as to send a man of his years aloft? Of all his starring Warner vehicles, Chain Lightning may be the one least mentioned today. I’ve always liked The Enforcer, but he’s the establishment figure crusading against crime here, and would continue doing so in the following year’s (1952) Deadline USA. There was now no question as to which side of the law Bogart was on. To see him back in (escaped) prisoner attire was all the more surprising in late-in-the-day The Desperate Hours. These were my youthful introductions to Bogart, for they were sold among syndication packages otherwise salted with color titles to satisfy broadcaster’s demand for something other than stale pre-48 groups. Dark Passage came my way by virtue of a backwoods station from Asheville we could barely pick up that probably never heard of color TV. Remember the hell of watching movies on local channels? They’d mutilate features to cram them into ninety-minute time frames, then spend a third of that on commercials and "Dialing For Dollars" nonsense. It’s a wonder any of us developed an interest in this stuff, let alone maintained it through years of sustained abuse and neglect. I remember one UHF outpost out of Charlotte that simply switched off Treasure Of the Sierra Madre with ten minutes left to go, just so they could move on to an episode of Davey and Goliath. Basking as we are in this era of TCM and DVD privilege, we forget how austere conditions once were. Most of us could fill a column with horror stories of wretched reception, relentless interruption, and jabbering hosts. Hey, that sounds like a like a ripe subject for a future Greenbriar posting…

You could say Dark Passage was the last of the vintage Bogart pictures. Treasure Of The Sierra Madre would point more toward character leads, and Key Largo was somehow loftier than lighter confections Huston had previously directed (Across the Pacific, which I prefer). No more convicts nor dwellings in moral twilight for Bogart. Chain Lightning would find him test-piloting in skies soon overpopulated with more conventional leading men, but what did Bogart have in common with William Holden, James Stewart, or John Wayne, and which branch of the service would be so remiss as to send a man of his years aloft? Of all his starring Warner vehicles, Chain Lightning may be the one least mentioned today. I’ve always liked The Enforcer, but he’s the establishment figure crusading against crime here, and would continue doing so in the following year’s (1952) Deadline USA. There was now no question as to which side of the law Bogart was on. To see him back in (escaped) prisoner attire was all the more surprising in late-in-the-day The Desperate Hours. These were my youthful introductions to Bogart, for they were sold among syndication packages otherwise salted with color titles to satisfy broadcaster’s demand for something other than stale pre-48 groups. Dark Passage came my way by virtue of a backwoods station from Asheville we could barely pick up that probably never heard of color TV. Remember the hell of watching movies on local channels? They’d mutilate features to cram them into ninety-minute time frames, then spend a third of that on commercials and "Dialing For Dollars" nonsense. It’s a wonder any of us developed an interest in this stuff, let alone maintained it through years of sustained abuse and neglect. I remember one UHF outpost out of Charlotte that simply switched off Treasure Of the Sierra Madre with ten minutes left to go, just so they could move on to an episode of Davey and Goliath. Basking as we are in this era of TCM and DVD privilege, we forget how austere conditions once were. Most of us could fill a column with horror stories of wretched reception, relentless interruption, and jabbering hosts. Hey, that sounds like a like a ripe subject for a future Greenbriar posting…

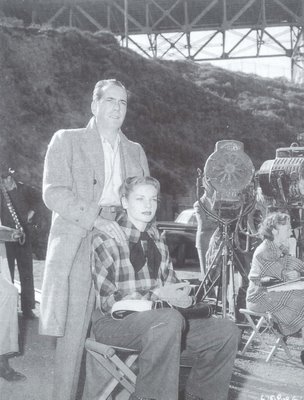

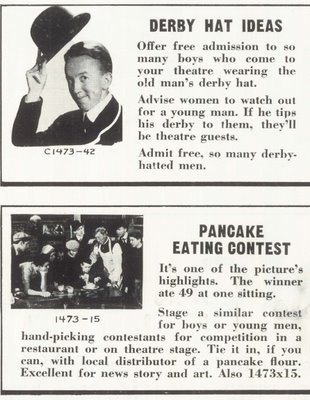

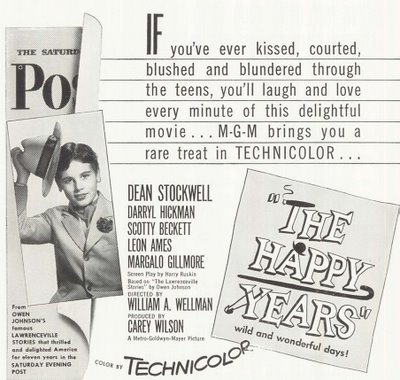

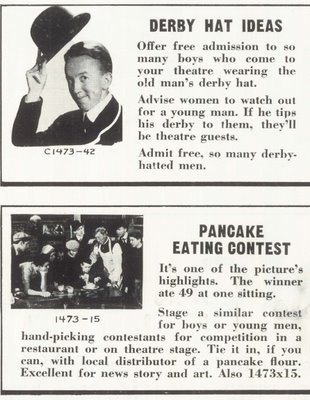

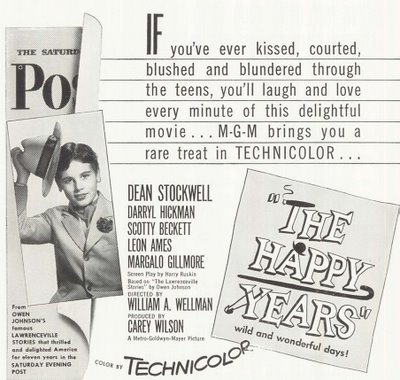

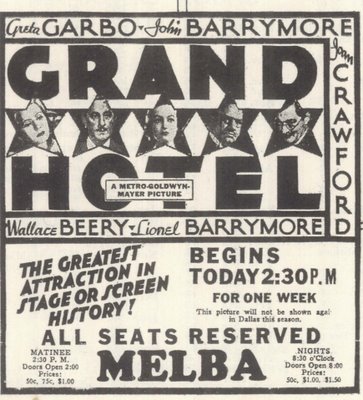

Those Happy Years Watching The Happy YearsSometimes a good picture can be jinxed by a campaign that refuses to jell --- then there are those shows left at the starting post as sales personnel devote themselves to more promising releases. Everything fell apart for The Happy Years from the moment it was trade-shown on May 24, 1950. MGM had unveiled Annie Get Your Gun to exhibitors the day before, and excitement had been building for another big one, Father Of The Bride. These were the leviathans that would roll over The Happy Years, and fifty-seven years later, it’s still on the canvas. We can only guess as to what went wrong, but trade scribes hinted at the problem. Ads covered with type and cluttered posters, said The Manager’s Round Table section of The Motion Picture Herald --- very little illustration, so you have to read to get the point. One-sheets were uninspired, as shown here, and limited to headshots of an unpresupposing cast. What exactly was Metro selling? No one seemed to get a handle on how to exploit The Happy Years. It was based on "beloved" stories that had run in The Saturday Evening Post over the last eleven years, but was Post reader familiarity enough to get back $1.3 million spent on this Technicolor period piece? Costumers were hard enough to merchandise with stars on board (witness The Tall Target), so how do you excite patrons over a boy’s prep school setting at the turn of the century? In the end, I suspect they just gave up. The Happy Years headed double bills with another MGM forfeit, Mystery Street (loss --- $277,000). This is a grand picture and deserved better results, said one showman concluding his dispirited run of The Happy Years. Worthy shows had been dumped before and would be again, but it was particularly sad seeing this one swept under the carpet. As Annie Get Your Gun and Father Of The Bride racked up enormous grosses, The Happy Years withered in the heat of a summer playoff and finished with an egregious $680,000 in domestic rentals, plus an appalling $179,000 foreign (again, that curse of Americana). A million-dollar loss was recorded in Metro ledgers, and there would be no re-issues, other than a few bookings among the MGM Children’s Matinee series of the early seventies where it was re-titled The Adventures Of Young Dink Stover. Those who cared might have seen The Happy Years previously on television, as it had gone into syndication for Fall 1964 with 39 other post-48 Metros. The (very) few prints in circulation among collectors were either heisted from Films, Inc. or some TV station. I’ve not yet met anyone who didn’t like this picture. Occasionally there are sightings on TCM, but otherwise The Happy Years is orphaned. There’s never been a video release. I’ve watched interviews with Dean Stockwell in hopes it would be mentioned, but he’d rather talk about the glories of having done Blue Velvet.

Those Happy Years Watching The Happy YearsSometimes a good picture can be jinxed by a campaign that refuses to jell --- then there are those shows left at the starting post as sales personnel devote themselves to more promising releases. Everything fell apart for The Happy Years from the moment it was trade-shown on May 24, 1950. MGM had unveiled Annie Get Your Gun to exhibitors the day before, and excitement had been building for another big one, Father Of The Bride. These were the leviathans that would roll over The Happy Years, and fifty-seven years later, it’s still on the canvas. We can only guess as to what went wrong, but trade scribes hinted at the problem. Ads covered with type and cluttered posters, said The Manager’s Round Table section of The Motion Picture Herald --- very little illustration, so you have to read to get the point. One-sheets were uninspired, as shown here, and limited to headshots of an unpresupposing cast. What exactly was Metro selling? No one seemed to get a handle on how to exploit The Happy Years. It was based on "beloved" stories that had run in The Saturday Evening Post over the last eleven years, but was Post reader familiarity enough to get back $1.3 million spent on this Technicolor period piece? Costumers were hard enough to merchandise with stars on board (witness The Tall Target), so how do you excite patrons over a boy’s prep school setting at the turn of the century? In the end, I suspect they just gave up. The Happy Years headed double bills with another MGM forfeit, Mystery Street (loss --- $277,000). This is a grand picture and deserved better results, said one showman concluding his dispirited run of The Happy Years. Worthy shows had been dumped before and would be again, but it was particularly sad seeing this one swept under the carpet. As Annie Get Your Gun and Father Of The Bride racked up enormous grosses, The Happy Years withered in the heat of a summer playoff and finished with an egregious $680,000 in domestic rentals, plus an appalling $179,000 foreign (again, that curse of Americana). A million-dollar loss was recorded in Metro ledgers, and there would be no re-issues, other than a few bookings among the MGM Children’s Matinee series of the early seventies where it was re-titled The Adventures Of Young Dink Stover. Those who cared might have seen The Happy Years previously on television, as it had gone into syndication for Fall 1964 with 39 other post-48 Metros. The (very) few prints in circulation among collectors were either heisted from Films, Inc. or some TV station. I’ve not yet met anyone who didn’t like this picture. Occasionally there are sightings on TCM, but otherwise The Happy Years is orphaned. There’s never been a video release. I’ve watched interviews with Dean Stockwell in hopes it would be mentioned, but he’d rather talk about the glories of having done Blue Velvet.

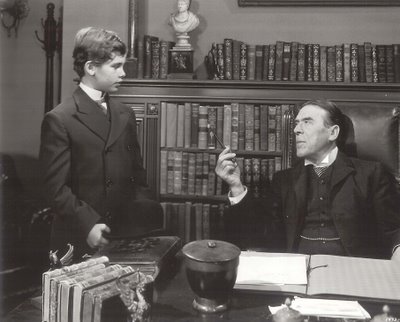

My father went to a boy’s school very much like Lawrenceville, the setting of The Happy Years. He particularly enjoyed the picture when we saw it on the old SFM Holiday Network presentation around 1981, but is there anyone left who would understand, even remotely, the student’s life he identified with? This was truly a movie for men who’d come of age near the turn of the (past) century. No one born since could comprehend, nor dramatize, that world so well. Producer Carey Wilson, born 1889, was enamoured of the project, having been a faithful reader of the Lawrenceville stories. Chances are he attended a place very much like it. Director William Wellman had been an outstanding athlete in high school, though it’s been suggested he never finished. He was born in 1896. These men brought an old-world sensibility to The Happy Years. Both were fascinated by the culture of a boy’s academy. I’ve not experienced a place such as Lawrenceville, but their details seem authentic. I’d like to think my father’s sojourn at the McCallie School in Chattanooga, Tennessee was similar. He boarded there in the late teens. The night we watched The Happy Years, he surprised me when he turned and said at the end, "Now that was really good," a reaction no picture had gotten from him in my memory. Maybe his own experience in that universe of The Happy Years gave him insights into its larger truths. It took men of a certain age to appreciate the crucial distinction between gerunds and gerundives.

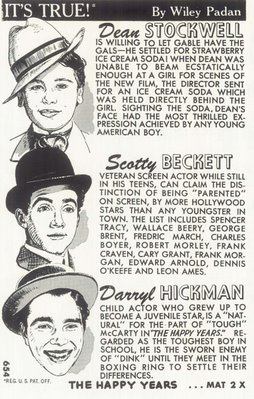

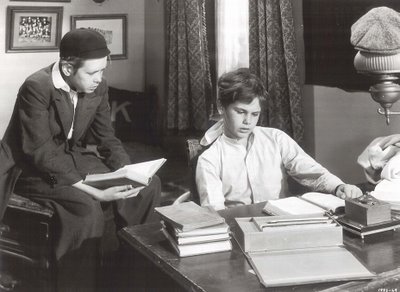

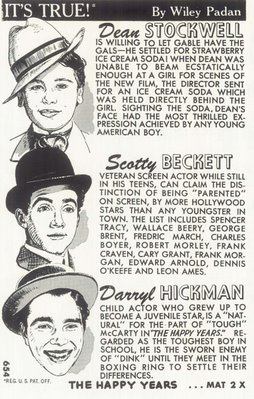

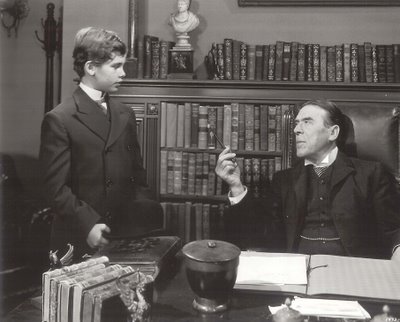

Youthful roles for Dean Stockwell, Darryl Hickman, and Scotty Beckett were nearly exhausted when they did The Happy Years. No longer boys in a cute sense, they were deep into adolescence and complications attendant thereto. Scotty had been arrested the year before for driving drunk. By the time The Happy Years went into production, he was twenty years old and married. The easy charm he projects in the movie was something he had plenty of in real life. It got him (barely) out of tough scrapes over a tumultuous adulthood until his luck ran out with a probable suicide (his third attempt) in 1968. Dean Stockwell was younger --- thirteen at the time The Happy Years was shot. This was his peak period, but late in the post-war day for child players to enter the game. He had the distinction of appearing in two classics released within weeks of each other --- Stars In My Crown and The Happy Years, but kid pictures of the kind MGM routinely turned out during the thirties and forties were disappearing fast, and Stockwell would only have a couple left before withdrawing several years to wait out puberty. Darryl Hickman was gangly and well past boy parts at eighteen, but he’d been in movies since If I Were King in 1938. He was on that Robert Osborne child star panel some months back and gave a good account of himself. I found it hard to believe someone so youthful in appearance and attitude could be seventy-five as of 2006. He has a book coming out in April, and it’s received advance praise. Also, there’s a website. Brother Dwayne’s in The Happy Years as well, though I’ve had no success spotting him. Neophyte Robert Wagner is recognizable, however.

Youthful roles for Dean Stockwell, Darryl Hickman, and Scotty Beckett were nearly exhausted when they did The Happy Years. No longer boys in a cute sense, they were deep into adolescence and complications attendant thereto. Scotty had been arrested the year before for driving drunk. By the time The Happy Years went into production, he was twenty years old and married. The easy charm he projects in the movie was something he had plenty of in real life. It got him (barely) out of tough scrapes over a tumultuous adulthood until his luck ran out with a probable suicide (his third attempt) in 1968. Dean Stockwell was younger --- thirteen at the time The Happy Years was shot. This was his peak period, but late in the post-war day for child players to enter the game. He had the distinction of appearing in two classics released within weeks of each other --- Stars In My Crown and The Happy Years, but kid pictures of the kind MGM routinely turned out during the thirties and forties were disappearing fast, and Stockwell would only have a couple left before withdrawing several years to wait out puberty. Darryl Hickman was gangly and well past boy parts at eighteen, but he’d been in movies since If I Were King in 1938. He was on that Robert Osborne child star panel some months back and gave a good account of himself. I found it hard to believe someone so youthful in appearance and attitude could be seventy-five as of 2006. He has a book coming out in April, and it’s received advance praise. Also, there’s a website. Brother Dwayne’s in The Happy Years as well, though I’ve had no success spotting him. Neophyte Robert Wagner is recognizable, however.

Variety suggested trims. The Happy Years was both leisurely and overlong. It’s admittedly relaxed as to pacing, but wasn’t life itself similarly laid back in those waning days of the gay nineties? I’d not vote to remove a moment of those 110 minutes, but much of that reflects my sentiment where this show is concerned. Was life so idyllic in that final decade of the nineteenth century? MGM certainly implied it was. Patriarch of choice Leon Ames is on hand as usual, and the comforting reassurance of that familiar Meet Me In St. Louis house (even against a beach set matte painting) made The Happy Years seem of a piece with the earlier musical hit. Red Skelton’s Excuse My Dust of the following year would utilize the same standing sets. Much of the furniture seen in The Happy Years would be used again here. The celebration of times long past would prevail at Fox with Cheaper By The Dozen, and Warner’s Booth Tarkington stories would accommodate Doris Day’s formula On Moonlight Bay and By The Light Of The Silvery Moon. These confections revolved around approximately the same period of American history. There must have been a fifties consensus that life in the nineties was simpler (if not preferable). Will we look back on any decade of the twentieth century with as much nostalgia? For a while, it seemed as though the sixties would reclaim us. American Graffiti ushered in a seventies longing for drive-ins and hopped-up cars, but that era seems now like ancient history (as do the seventies themselves). It’s hard to imagine anyone wanting to revisit our recently past eighties and nineties, but who knows? --- there must be someone with nostalgic recollections of those benighted decades. Why would movies ever embrace the nineteenth century again? Might as well revisit lives of the pharaohs , and that’s all the more reason to treasure The Happy Years, because we’re never going to get pictures the likes of this again. The people who could mount them are gone and they didn’t leave instructions behind.

Variety suggested trims. The Happy Years was both leisurely and overlong. It’s admittedly relaxed as to pacing, but wasn’t life itself similarly laid back in those waning days of the gay nineties? I’d not vote to remove a moment of those 110 minutes, but much of that reflects my sentiment where this show is concerned. Was life so idyllic in that final decade of the nineteenth century? MGM certainly implied it was. Patriarch of choice Leon Ames is on hand as usual, and the comforting reassurance of that familiar Meet Me In St. Louis house (even against a beach set matte painting) made The Happy Years seem of a piece with the earlier musical hit. Red Skelton’s Excuse My Dust of the following year would utilize the same standing sets. Much of the furniture seen in The Happy Years would be used again here. The celebration of times long past would prevail at Fox with Cheaper By The Dozen, and Warner’s Booth Tarkington stories would accommodate Doris Day’s formula On Moonlight Bay and By The Light Of The Silvery Moon. These confections revolved around approximately the same period of American history. There must have been a fifties consensus that life in the nineties was simpler (if not preferable). Will we look back on any decade of the twentieth century with as much nostalgia? For a while, it seemed as though the sixties would reclaim us. American Graffiti ushered in a seventies longing for drive-ins and hopped-up cars, but that era seems now like ancient history (as do the seventies themselves). It’s hard to imagine anyone wanting to revisit our recently past eighties and nineties, but who knows? --- there must be someone with nostalgic recollections of those benighted decades. Why would movies ever embrace the nineteenth century again? Might as well revisit lives of the pharaohs , and that’s all the more reason to treasure The Happy Years, because we’re never going to get pictures the likes of this again. The people who could mount them are gone and they didn’t leave instructions behind.

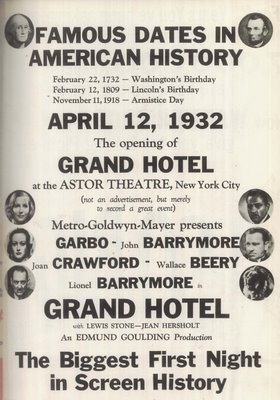

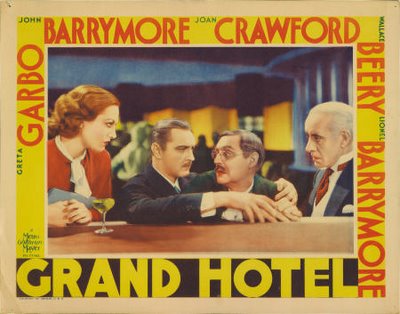

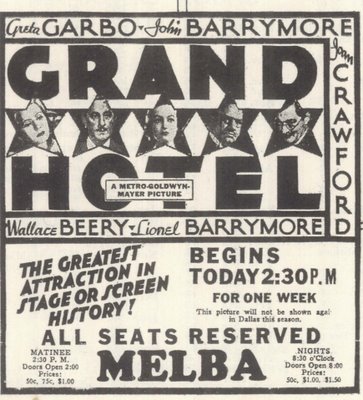

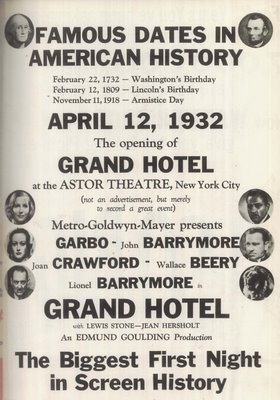

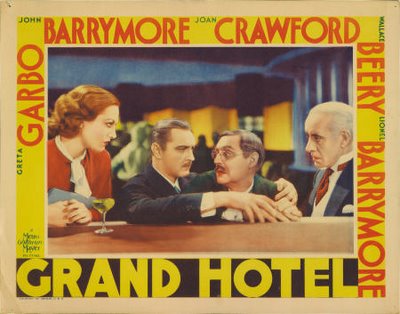

The Grand Hotel That Might Have BeenCasting what-ifs are a real waste of time in most cases, but one I would indulge concerns the legendary all-star Grand Hotel and the movie that might have been had MGM gone with their initial choices. Good as the finished product is, I can’t help wishing they’d stuck with the line-up as announced (if tentatively) in early trade mentions. There was a lot of interest in this property growing out of the play it was based on, and by December 1931, columnists were speculating on who might fill roles familiar from the stage version. The Hollywood Reporter posted a tentative line-up that month. Clark Gable, Buster Keaton, Jimmy Durante, and George E. Stone suggested something along comedic lines. Was Grand Hotel played more for laughs in its legit presentation? As late as December 28, Gable was "unofficially" tabbed for the project, even as shooting was to start in less than a week. Then there was John Gilbert, who’d eventually be replaced by John Barrymore. How close were these players to roles that would surely have changed the course of their careers, and in the case of Gilbert and Keaton, might possibly save them? What would it have been like to covet a part in a sure-fire major hit --- come so close to the realization of your desire --- then have it snatched away only days before production? If nothing else, the saga of Grand Hotel demonstrates just how capricious casting decisions could be, and how easily one missed (or gained) opportunity could hasten (or impede) a star’s momentum. A single Grand Hotel was worth a dozen ordinary vehicles. No studio (even Metro) was good for more than one or two such specials in any given year. You could coast a long time on a picture big as this …

The Grand Hotel That Might Have BeenCasting what-ifs are a real waste of time in most cases, but one I would indulge concerns the legendary all-star Grand Hotel and the movie that might have been had MGM gone with their initial choices. Good as the finished product is, I can’t help wishing they’d stuck with the line-up as announced (if tentatively) in early trade mentions. There was a lot of interest in this property growing out of the play it was based on, and by December 1931, columnists were speculating on who might fill roles familiar from the stage version. The Hollywood Reporter posted a tentative line-up that month. Clark Gable, Buster Keaton, Jimmy Durante, and George E. Stone suggested something along comedic lines. Was Grand Hotel played more for laughs in its legit presentation? As late as December 28, Gable was "unofficially" tabbed for the project, even as shooting was to start in less than a week. Then there was John Gilbert, who’d eventually be replaced by John Barrymore. How close were these players to roles that would surely have changed the course of their careers, and in the case of Gilbert and Keaton, might possibly save them? What would it have been like to covet a part in a sure-fire major hit --- come so close to the realization of your desire --- then have it snatched away only days before production? If nothing else, the saga of Grand Hotel demonstrates just how capricious casting decisions could be, and how easily one missed (or gained) opportunity could hasten (or impede) a star’s momentum. A single Grand Hotel was worth a dozen ordinary vehicles. No studio (even Metro) was good for more than one or two such specials in any given year. You could coast a long time on a picture big as this …

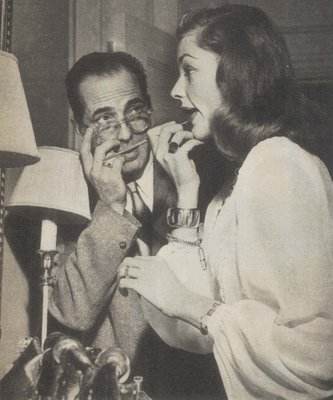

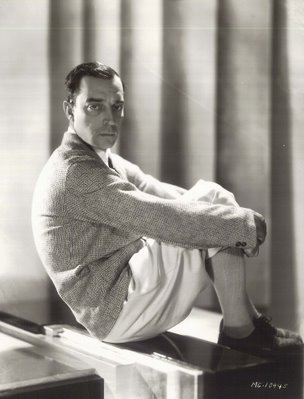

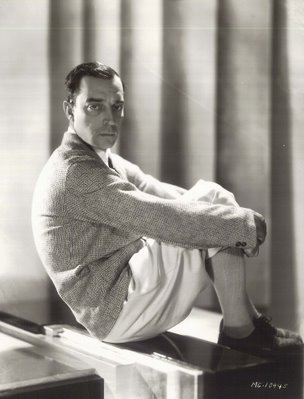

John Gilbert had cruised on the fabulous success of The Big Parade and other silent favorites, until sound closed the book on his stardom. The lucrative contract he’d signed with Loew’s chairman Nicholas Schenck guaranteed three years of top money and starring berths at MGM, but Schenck never dreamed Jack’s audience would abandon him so cruelly and suddenly. Animus on Louis Mayer’s part foreclosed serious efforts to rehabilitate a faltering image, and by 1930, Gilbert was declared washed up. One great picture might have saved him. There was nothing wrong with his appearance, as the overuse of alcohol had not yet made those inroads, but how could performances in things like West Of Broadway and A Gentleman’s Fate seem anything other than dispirited? There were only eight months to go on Gilbert’s contract in December 1931, and time was running out on a comeback, if not the actor’s health. He’d suffered with insomnia, bleeding stomach ulcers, and alcoholism that had progressed to a point where one drink made him deathly sick. It was understood early on that Grand Hotel would star John Gilbert, but that was when Metro first invested in the play, and before his last four pictures tanked. Though it too lost money, The Phantom Of Paris (shown here) was actually a major improvement upon previous films, and reviews had not been so generous since Gilbert’s silent heyday. Phantom plays well yet, as demonstrated on frequent TCM broadcasts, and he’s relaxed and assured at all times. If there was a crisis of confidence, Gilbert had overcome it with this performance. Jack thought he had a friend in Irving Thalberg, and indeed, they enjoyed a congenial social relationship, having known each other since the early twenties, but Thalberg was first and always a company man, and playing bridge with him on Sunday was no guarantee he’d cast you on Monday. Jack would now beg for the opportunity to do Grand Hotel. He kidded of ideal casting as a dissolute baron and faded lover, but few laughed with him. Greta Garbo seems to have wanted Gilbert, but when the prospect of Barrymore was dangled before her, all bets were off and Jack was out. I’d read that disappointment over Grand Hotel ended the star’s friendship with Thalberg, but evidence suggests otherwise, for by June of 1932, Gilbert was starring in a story he’d written entitled Downstairs, perhaps consolation for missing Grand Hotel, and far and away his finest work in talkies. The truly crushing blow came with Red Dust, which had been definitely set for Gilbert until Clark Gable’s ascent dictated otherwise. As this one didn’t go into production until August 1932, it did, in any case, miss the expiration date of Gilbert’s contract (July 31). If there was a rupture in the Gilbert/Thalberg relationship, this is probably where it occurred, and yet they were photographed together as late as November of that same year, as shown here (that’s Gilbert and new wife Virginia Bruce in a foursome with Norma Shearer and Thalberg).

John Gilbert had cruised on the fabulous success of The Big Parade and other silent favorites, until sound closed the book on his stardom. The lucrative contract he’d signed with Loew’s chairman Nicholas Schenck guaranteed three years of top money and starring berths at MGM, but Schenck never dreamed Jack’s audience would abandon him so cruelly and suddenly. Animus on Louis Mayer’s part foreclosed serious efforts to rehabilitate a faltering image, and by 1930, Gilbert was declared washed up. One great picture might have saved him. There was nothing wrong with his appearance, as the overuse of alcohol had not yet made those inroads, but how could performances in things like West Of Broadway and A Gentleman’s Fate seem anything other than dispirited? There were only eight months to go on Gilbert’s contract in December 1931, and time was running out on a comeback, if not the actor’s health. He’d suffered with insomnia, bleeding stomach ulcers, and alcoholism that had progressed to a point where one drink made him deathly sick. It was understood early on that Grand Hotel would star John Gilbert, but that was when Metro first invested in the play, and before his last four pictures tanked. Though it too lost money, The Phantom Of Paris (shown here) was actually a major improvement upon previous films, and reviews had not been so generous since Gilbert’s silent heyday. Phantom plays well yet, as demonstrated on frequent TCM broadcasts, and he’s relaxed and assured at all times. If there was a crisis of confidence, Gilbert had overcome it with this performance. Jack thought he had a friend in Irving Thalberg, and indeed, they enjoyed a congenial social relationship, having known each other since the early twenties, but Thalberg was first and always a company man, and playing bridge with him on Sunday was no guarantee he’d cast you on Monday. Jack would now beg for the opportunity to do Grand Hotel. He kidded of ideal casting as a dissolute baron and faded lover, but few laughed with him. Greta Garbo seems to have wanted Gilbert, but when the prospect of Barrymore was dangled before her, all bets were off and Jack was out. I’d read that disappointment over Grand Hotel ended the star’s friendship with Thalberg, but evidence suggests otherwise, for by June of 1932, Gilbert was starring in a story he’d written entitled Downstairs, perhaps consolation for missing Grand Hotel, and far and away his finest work in talkies. The truly crushing blow came with Red Dust, which had been definitely set for Gilbert until Clark Gable’s ascent dictated otherwise. As this one didn’t go into production until August 1932, it did, in any case, miss the expiration date of Gilbert’s contract (July 31). If there was a rupture in the Gilbert/Thalberg relationship, this is probably where it occurred, and yet they were photographed together as late as November of that same year, as shown here (that’s Gilbert and new wife Virginia Bruce in a foursome with Norma Shearer and Thalberg).

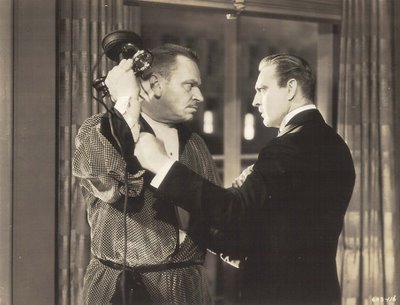

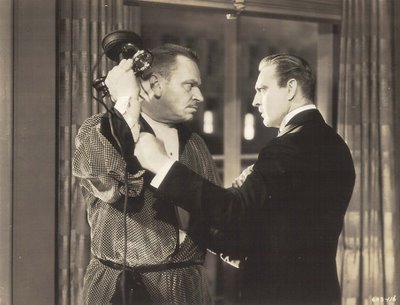

Clark Gable was actually considered for the Wallace Beery part, less surprising when you consider the brutish roles he’d essayed over the past year when the caveman image was taking shape. A Free Soul suggests Gable would have been ideal in Beery's part. No doubt he’d have made explicit what was merely implied by the relationship between Beery and Joan Crawford in Grand Hotel as we know it. The tension between he and Gilbert over Crawford (or perhaps even Garbo!) would have created sparks altogether missing from the more or less placid conflict played out by Barrymore and Beery. Columnist Elizabeth Yeaman posted the news on December 28, 1931 that Gable was "unofficially" set for the film, while Jimmy Starr would announce (within ten days) China Seas as the actor’s next starring role (though it would be three years before that one came to fruition). By January 13, Gable was definitely booked for Strange Interlude with Norma Shearer, which was filmed that Spring. Grand Hotel would have been a great role for the rough-edged, early Gable. Imagine that hotel room confrontation between he and Gilbert. The talkie’s newest romantic idol bashing in the head of a discarded silent lover --- and with a telephone receiver. Talk about a merger of art with life! Too bad we missed out on it. The demand for Gable was so great that to use him in an all-star feature might have been considered wasteful, and yet he’d be on hand a year later for Night Flight, with its similarly loaded marquee. His screen character would begin to soften after Red Dust (released October 1932), and the hard exterior would receive further massaging in musicals (Dancing Lady), reformation stories (Hold Your Man), and finally, romance comedy (It Happened One Night). Code artisans and studio image-makers chiseled away at Gable the Love Menace and found a lovable scamp underneath; safely (and reliably) marketable over the long haul, but with much of the edge gone forever. Audiences would forget thuggish, almost simian qualities of a pre-code beginner. When Robert Youngson included a particularly nasty clip from Night Nurse in his 1955 Warners compilation short, When The Talkies Were Young, viewers were startled to see their beloved (and by now firmly establishment) icon dressed up in storm trooper-ish chauffeur’s uniform and roughing up Barbara Stanwyck. The elapse of so many years, and a virtual disappearance of the films themselves, erased memories of Gable the primitive. Had he been given Grand Hotel, probably the most noted of all early-30’s MGM features, they might better have remembered this star in his formative period.

Clark Gable was actually considered for the Wallace Beery part, less surprising when you consider the brutish roles he’d essayed over the past year when the caveman image was taking shape. A Free Soul suggests Gable would have been ideal in Beery's part. No doubt he’d have made explicit what was merely implied by the relationship between Beery and Joan Crawford in Grand Hotel as we know it. The tension between he and Gilbert over Crawford (or perhaps even Garbo!) would have created sparks altogether missing from the more or less placid conflict played out by Barrymore and Beery. Columnist Elizabeth Yeaman posted the news on December 28, 1931 that Gable was "unofficially" set for the film, while Jimmy Starr would announce (within ten days) China Seas as the actor’s next starring role (though it would be three years before that one came to fruition). By January 13, Gable was definitely booked for Strange Interlude with Norma Shearer, which was filmed that Spring. Grand Hotel would have been a great role for the rough-edged, early Gable. Imagine that hotel room confrontation between he and Gilbert. The talkie’s newest romantic idol bashing in the head of a discarded silent lover --- and with a telephone receiver. Talk about a merger of art with life! Too bad we missed out on it. The demand for Gable was so great that to use him in an all-star feature might have been considered wasteful, and yet he’d be on hand a year later for Night Flight, with its similarly loaded marquee. His screen character would begin to soften after Red Dust (released October 1932), and the hard exterior would receive further massaging in musicals (Dancing Lady), reformation stories (Hold Your Man), and finally, romance comedy (It Happened One Night). Code artisans and studio image-makers chiseled away at Gable the Love Menace and found a lovable scamp underneath; safely (and reliably) marketable over the long haul, but with much of the edge gone forever. Audiences would forget thuggish, almost simian qualities of a pre-code beginner. When Robert Youngson included a particularly nasty clip from Night Nurse in his 1955 Warners compilation short, When The Talkies Were Young, viewers were startled to see their beloved (and by now firmly establishment) icon dressed up in storm trooper-ish chauffeur’s uniform and roughing up Barbara Stanwyck. The elapse of so many years, and a virtual disappearance of the films themselves, erased memories of Gable the primitive. Had he been given Grand Hotel, probably the most noted of all early-30’s MGM features, they might better have remembered this star in his formative period.

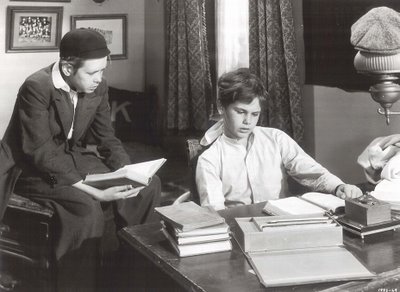

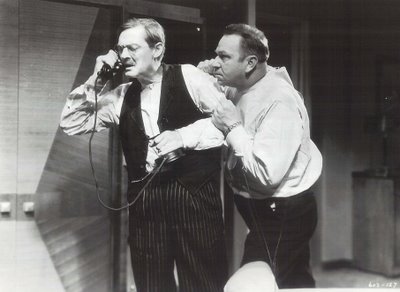

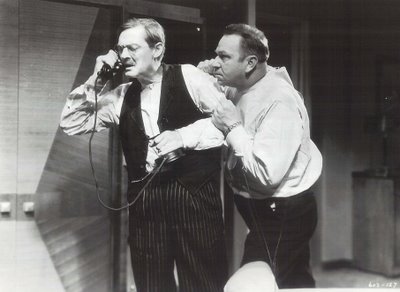

Would Buster Keaton have been spared the fate of Educational and Columbia two-reelers had he played Otto Kringelin (Lionel Barrymore’s eventual part) in Grand Hotel? To the end of his life, the comedian maintained he’d have done an efficient job of it, and if you look at Buster’s 1954 dramatic debut in The Awakening, an episode of Douglas Fairbanks Jr’s anthology series, there’s no doubt he was equal to the task of serious emoting. Grand Hotel director Edmund Goulding fired the idea in Keaton when he sent for him in late 1931. I make it a rule to become very serious about the fourth reel or so. That is to make absolutely sure that the audience will really care about what happens to me in the rest of the picture, said the comedian in his 1960 memoir, My Wonderful World Of Slapstick. Sounds like inspired off-casting for a star long dissatisfied with lousy assignments he’d been getting. The only good thing about Sidewalks Of New York and Parlor, Bedroom, and Bath were the profits they were earning. I was sure I could handle such a serious part --- but was the departure so radical? Lionel Barrymore's Kringelin evokes Buster at times (I would have played the part differently. I do not say better, mind you, just differently, said Keaton). Kringelin is the only major character in Grand Hotel that allows for comedy, and Buster could easily have woven some of that into the drama (his timid professor in Speak Easily, shown here, suggests Kringelin, in looks if not manner). Goulding’s strong direction and the challenge of work with major talent would no doubt have restored assurance Keaton had lost after those forced marches through poor vehicles. It would appear he lost the role when just cast John Barrymore insisted on brother Lionel as Kringelin. Disappointment over this may have been a major factor in exacerbating Buster’s drinking problem, for now there was only the prospect of a revised contract (for but a single year and with terms unfavorable to him) along with an increasingly prominent co-star (Jimmy Durante), whose star was rising even as Keaton’s fell. While Grand Hotel triumphed in general release, Buster was fast headed toward career crisis, and no one was surprised when the studio ax fell on February 2, 1933. Whatever future he might have had as a character actor (make that serio-comic star), similar indeed to what Lionel Barrymore enjoyed up to his death in 1954, was now lost to Keaton.

Would Buster Keaton have been spared the fate of Educational and Columbia two-reelers had he played Otto Kringelin (Lionel Barrymore’s eventual part) in Grand Hotel? To the end of his life, the comedian maintained he’d have done an efficient job of it, and if you look at Buster’s 1954 dramatic debut in The Awakening, an episode of Douglas Fairbanks Jr’s anthology series, there’s no doubt he was equal to the task of serious emoting. Grand Hotel director Edmund Goulding fired the idea in Keaton when he sent for him in late 1931. I make it a rule to become very serious about the fourth reel or so. That is to make absolutely sure that the audience will really care about what happens to me in the rest of the picture, said the comedian in his 1960 memoir, My Wonderful World Of Slapstick. Sounds like inspired off-casting for a star long dissatisfied with lousy assignments he’d been getting. The only good thing about Sidewalks Of New York and Parlor, Bedroom, and Bath were the profits they were earning. I was sure I could handle such a serious part --- but was the departure so radical? Lionel Barrymore's Kringelin evokes Buster at times (I would have played the part differently. I do not say better, mind you, just differently, said Keaton). Kringelin is the only major character in Grand Hotel that allows for comedy, and Buster could easily have woven some of that into the drama (his timid professor in Speak Easily, shown here, suggests Kringelin, in looks if not manner). Goulding’s strong direction and the challenge of work with major talent would no doubt have restored assurance Keaton had lost after those forced marches through poor vehicles. It would appear he lost the role when just cast John Barrymore insisted on brother Lionel as Kringelin. Disappointment over this may have been a major factor in exacerbating Buster’s drinking problem, for now there was only the prospect of a revised contract (for but a single year and with terms unfavorable to him) along with an increasingly prominent co-star (Jimmy Durante), whose star was rising even as Keaton’s fell. While Grand Hotel triumphed in general release, Buster was fast headed toward career crisis, and no one was surprised when the studio ax fell on February 2, 1933. Whatever future he might have had as a character actor (make that serio-comic star), similar indeed to what Lionel Barrymore enjoyed up to his death in 1954, was now lost to Keaton.

Keaton's absorption with Grand Hotel would continue. An idea for a "travesty" was presented to a polite, but indifferent Thalberg (Aside from Norma Shearer, his wife, I think I was his favorite MGM star, said Buster in later years, but wasn’t this merely an echo of John Gilbert’s hopeful supposition?). Keaton’s lampoon would utilize the standing hotel set and a cast of comedians sending up histrionics from the lately released blockbuster, but his framework for this farce suggested Buster himself had become another Metro pod person. He’d finally play Kringelin, but this time with life-threatening hiccups. Laurel and Hardy would be competing collar-button manufacturers. Polly Moran (in the Crawford role) was penciled in as the object of Hardy’s would-be seduction. As if to confirm whatever doubts one might have about his creative judgement, Keaton proposed Jimmy Durante for the John Barrymore role, with Marie Dressler as a strident Garbo substitute. The idea went nowhere, though the comedian would add a postscript decades later when preparing My Wonderful World Of Slapstick. It seems Thalberg did call back, but only after Buster had been sacked from MGM. Grand Mills Hotel was a go if Keaton was willing. Everything might have been different if I had gone back, but was the invitation actually extended? There’s reason to believe it wasn’t, but perhaps Buster needed something to cling to, even if it was the misguided notion that it was he who rejected Metro this time, and that his million-dollar concept was one they bungled.

Keaton's absorption with Grand Hotel would continue. An idea for a "travesty" was presented to a polite, but indifferent Thalberg (Aside from Norma Shearer, his wife, I think I was his favorite MGM star, said Buster in later years, but wasn’t this merely an echo of John Gilbert’s hopeful supposition?). Keaton’s lampoon would utilize the standing hotel set and a cast of comedians sending up histrionics from the lately released blockbuster, but his framework for this farce suggested Buster himself had become another Metro pod person. He’d finally play Kringelin, but this time with life-threatening hiccups. Laurel and Hardy would be competing collar-button manufacturers. Polly Moran (in the Crawford role) was penciled in as the object of Hardy’s would-be seduction. As if to confirm whatever doubts one might have about his creative judgement, Keaton proposed Jimmy Durante for the John Barrymore role, with Marie Dressler as a strident Garbo substitute. The idea went nowhere, though the comedian would add a postscript decades later when preparing My Wonderful World Of Slapstick. It seems Thalberg did call back, but only after Buster had been sacked from MGM. Grand Mills Hotel was a go if Keaton was willing. Everything might have been different if I had gone back, but was the invitation actually extended? There’s reason to believe it wasn’t, but perhaps Buster needed something to cling to, even if it was the misguided notion that it was he who rejected Metro this time, and that his million-dollar concept was one they bungled.

Region 2 Round-Up --- Part Two

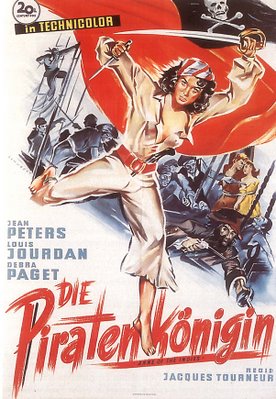

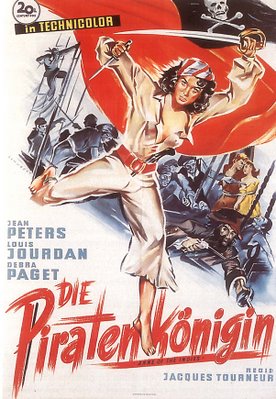

Region 2 Round-Up --- Part Two I knew Anne Of the Indies was in trouble when she had captives walking a plank (and falling to their deaths) during the opening reel of this most enjoyable 20th Fox pirate adventure directed by Jacques Tourneur. Jean Peters would either have to die at the end or be "brought to justice." Distaff pirates require a suspension of disbelief beyond even that customary with pictures of this type, and you could say Peters is no more credible than Maureen O’Hara, Hillary Brooke, Geena Davis, or other members of that rarefied sorority. Very much like The Black Swan, only better, Anne Of the Indies got on and off in less than 80 minutes (at least by the speeded up clock of Region 2 PAL conversion), and took its place near the top of my favorite Tourneurs list (along with his three Lewtons, Canyon Passage, Out Of The Past, Stars In My Crown, and Curse Of The Demon). Offbeat touches include a pirate’s wrestling match with a bear, affording us a glimpse of what that legendarily deleted scene from The Wolf Man might have looked like. Fetching Jean Peters seems at all times a high school girl playing at piracy, but who’d want her muscled-up and butchy, as modern-day agenda loyalists would no doubt enact this role? Louis Jourdon’s fragility suggests he might be dominated by such an opponent, though the choice he’s obliged to make between Jean Peters and Debra Paget would be an enviable, if ultimately frustrating, one. Peters makes good on the promise of duel scenes pictured in ads and posters (a European one shown here). I watched the sword action closely and detected little in the way of doubling. Maybe this actress embraced those obligatory fencing lessons contract players had to take whenever they signed on with big studios. She must surely have considered Anne Of the Indies one of her more rewarding parts, though I can’t recall having seen a published interview with Jean after she retired in 1955. Anybody know of one? Fox memos of the time recognized Anne Of The Indies’ appeal to worldwide audiences. Zanuck noted domestic rentals ($1.2 million) that fell short of the negative cost ($1.4), but cited outstanding foreign receipts ($1.5 million) that put the picture into a modest profit of $111,000. He warned of pictures too dependent upon US returns, such as I’d Climb The Highest Mountain, Wait Till The Sun Shines, Nellie, and other Americana subjects, having hard climbs toward breaking even without elements attractive to worldwide markets. Judging by deluxe presentation on the import DVD, Anne Of The Indies has maintained its stature among French viewers (Tourneur’s considerable auteurist rep helps). We seem to have forgotten all about this show stateside. Fox never released it in any home video format, and I can’t recall seeing Anne Of The Indies on AMC or the company’s Movie Channel (for that matter, I never even encountered a decent 16mm print in color). With everyone so enraptured by pirates of the Caribbean, I’m surprised Fox hasn’t at least released Anne as a bare-bones DVD. Ordering it HERE may indeed be our only recourse for some time to come.

I knew Anne Of the Indies was in trouble when she had captives walking a plank (and falling to their deaths) during the opening reel of this most enjoyable 20th Fox pirate adventure directed by Jacques Tourneur. Jean Peters would either have to die at the end or be "brought to justice." Distaff pirates require a suspension of disbelief beyond even that customary with pictures of this type, and you could say Peters is no more credible than Maureen O’Hara, Hillary Brooke, Geena Davis, or other members of that rarefied sorority. Very much like The Black Swan, only better, Anne Of the Indies got on and off in less than 80 minutes (at least by the speeded up clock of Region 2 PAL conversion), and took its place near the top of my favorite Tourneurs list (along with his three Lewtons, Canyon Passage, Out Of The Past, Stars In My Crown, and Curse Of The Demon). Offbeat touches include a pirate’s wrestling match with a bear, affording us a glimpse of what that legendarily deleted scene from The Wolf Man might have looked like. Fetching Jean Peters seems at all times a high school girl playing at piracy, but who’d want her muscled-up and butchy, as modern-day agenda loyalists would no doubt enact this role? Louis Jourdon’s fragility suggests he might be dominated by such an opponent, though the choice he’s obliged to make between Jean Peters and Debra Paget would be an enviable, if ultimately frustrating, one. Peters makes good on the promise of duel scenes pictured in ads and posters (a European one shown here). I watched the sword action closely and detected little in the way of doubling. Maybe this actress embraced those obligatory fencing lessons contract players had to take whenever they signed on with big studios. She must surely have considered Anne Of the Indies one of her more rewarding parts, though I can’t recall having seen a published interview with Jean after she retired in 1955. Anybody know of one? Fox memos of the time recognized Anne Of The Indies’ appeal to worldwide audiences. Zanuck noted domestic rentals ($1.2 million) that fell short of the negative cost ($1.4), but cited outstanding foreign receipts ($1.5 million) that put the picture into a modest profit of $111,000. He warned of pictures too dependent upon US returns, such as I’d Climb The Highest Mountain, Wait Till The Sun Shines, Nellie, and other Americana subjects, having hard climbs toward breaking even without elements attractive to worldwide markets. Judging by deluxe presentation on the import DVD, Anne Of The Indies has maintained its stature among French viewers (Tourneur’s considerable auteurist rep helps). We seem to have forgotten all about this show stateside. Fox never released it in any home video format, and I can’t recall seeing Anne Of The Indies on AMC or the company’s Movie Channel (for that matter, I never even encountered a decent 16mm print in color). With everyone so enraptured by pirates of the Caribbean, I’m surprised Fox hasn’t at least released Anne as a bare-bones DVD. Ordering it HERE may indeed be our only recourse for some time to come.

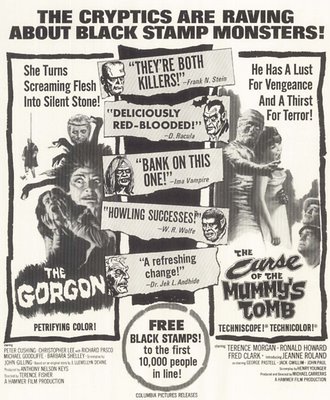

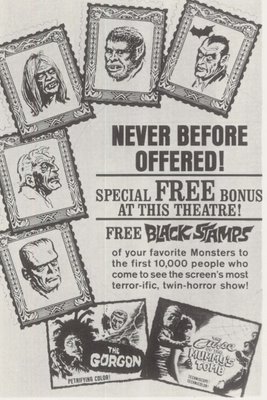

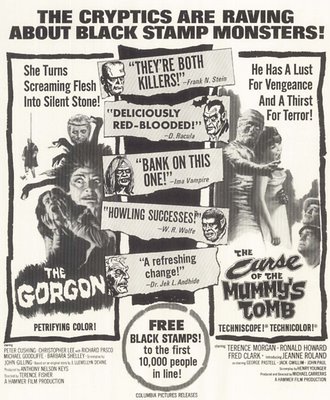

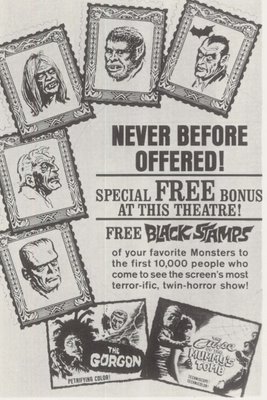

Horror/sci-fi combos were that much tougher to sell by the mid-sixties when Columbia released another two Hammer chillers stateside. Memories of block-round lines for Curse Of Frankenstein in 1957 and Horror Of Dracula in 1958 still inspired confidence that perhaps lightning could strike just once more, but these selfsame monsters were now running loose all over television, and the novelty of watching them spill a little more blood in theatres had long since past. Worse still, fans were beginning to access color horror movies on their TV’s, even some of the early (and better) Hammers. Increasingly silly campaigns were adjudged the answer, as shown here with "Black Stamp" giveaways to accompany the combo of Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb and The Gorgon (she had a face only a Mummy could love --- was MAD magazine now composing ad copy?). The stamps reminded me of something included with those nauseating sheets of bubble gum that would snap in two when you opened the pack and proved near impossible to chew (lest you were willing to sacrifice what was left of your baby teeth doing so). The fact stamps were available to the first 10,000 people in line reflected foolhardy optimism on Columbia’s part unlikely to be fulfilled at any venue running these two. Our beloved Liberty played the combo (first Saturday after school let out in June 1965), but nixed on Black Stamps, possibly in avoidance of giving them away clear through to 1972 as means of stock dosposal. How refreshing then, to find Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb and The Gorgon departing well from antic salesmanship Columbia inflicted upon them, both being literate and effective chillers. I eagerly await The Gorgon’s arrival on DVD (and hope it’ll be like the stunner broadcast on Monsters HD last year), but in a meantime, we have Curse Of the Mummy’s Tomb just out on Region 2 from the UK. Some aver Hammer reached beyond grasp here, but I admire this ambitious storyline of brother pharaohs' sustained rivalry through centuries. Why not direct as though you were David Lean and this was Lawrence Of Arabia? --- and indeed, Michael Carreras does. Characters are unpredictable, none are sympathetic, and all benefit from seasoned British thesps portraying them. I could wish this mummy weren't encased in a loose-fitting union suit (with all but a buttoned flap on its rear), but Hammer enjoyed not the luxuries of Jack Pierce make-up nor eight-hours necessary to apply it. We were impressed in 1965 by a generous helping of limb-lobbing, but why this emphasis upon hands being severed? Something to do with that ancient curse, as I realized during more recent screenings, but chances are you’ll opt for protective mittens, or at the least very long sleeves, after viewing Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb. By way of declining revenue, even Black Stamps weren’t enough to prevent tide going out on Hammer horrors. This Mummy drew but $218,000 in domestic rentals, significantly less than Columbia’s homegrown shockers. Straight Jacket had pulled $1.7 million. A sci-fi with more promotion backing it, First Men In The Moon, scored $887,000. Even a same-year Hammer they handled, Die! Die! My Darling, took nearly twice the Mummy’s haul with $400,000.

Horror/sci-fi combos were that much tougher to sell by the mid-sixties when Columbia released another two Hammer chillers stateside. Memories of block-round lines for Curse Of Frankenstein in 1957 and Horror Of Dracula in 1958 still inspired confidence that perhaps lightning could strike just once more, but these selfsame monsters were now running loose all over television, and the novelty of watching them spill a little more blood in theatres had long since past. Worse still, fans were beginning to access color horror movies on their TV’s, even some of the early (and better) Hammers. Increasingly silly campaigns were adjudged the answer, as shown here with "Black Stamp" giveaways to accompany the combo of Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb and The Gorgon (she had a face only a Mummy could love --- was MAD magazine now composing ad copy?). The stamps reminded me of something included with those nauseating sheets of bubble gum that would snap in two when you opened the pack and proved near impossible to chew (lest you were willing to sacrifice what was left of your baby teeth doing so). The fact stamps were available to the first 10,000 people in line reflected foolhardy optimism on Columbia’s part unlikely to be fulfilled at any venue running these two. Our beloved Liberty played the combo (first Saturday after school let out in June 1965), but nixed on Black Stamps, possibly in avoidance of giving them away clear through to 1972 as means of stock dosposal. How refreshing then, to find Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb and The Gorgon departing well from antic salesmanship Columbia inflicted upon them, both being literate and effective chillers. I eagerly await The Gorgon’s arrival on DVD (and hope it’ll be like the stunner broadcast on Monsters HD last year), but in a meantime, we have Curse Of the Mummy’s Tomb just out on Region 2 from the UK. Some aver Hammer reached beyond grasp here, but I admire this ambitious storyline of brother pharaohs' sustained rivalry through centuries. Why not direct as though you were David Lean and this was Lawrence Of Arabia? --- and indeed, Michael Carreras does. Characters are unpredictable, none are sympathetic, and all benefit from seasoned British thesps portraying them. I could wish this mummy weren't encased in a loose-fitting union suit (with all but a buttoned flap on its rear), but Hammer enjoyed not the luxuries of Jack Pierce make-up nor eight-hours necessary to apply it. We were impressed in 1965 by a generous helping of limb-lobbing, but why this emphasis upon hands being severed? Something to do with that ancient curse, as I realized during more recent screenings, but chances are you’ll opt for protective mittens, or at the least very long sleeves, after viewing Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb. By way of declining revenue, even Black Stamps weren’t enough to prevent tide going out on Hammer horrors. This Mummy drew but $218,000 in domestic rentals, significantly less than Columbia’s homegrown shockers. Straight Jacket had pulled $1.7 million. A sci-fi with more promotion backing it, First Men In The Moon, scored $887,000. Even a same-year Hammer they handled, Die! Die! My Darling, took nearly twice the Mummy’s haul with $400,000.

Merrill’s Marauders was an even then (1962) old-fashioned war movie lacking the sharper edge one expects from renegade director Samuel Fuller. Could Jack Warner have dictated they stick closer to the Objective, Burma model (even to the extent of reusing much of its score)? Credited co-writer and Warner son-in-law Milton Sperling might have subverted Fuller’s customarily hard-bitten approach to combat subjects. This was, after all, a bigger budget show, and off-putting realism of a Steel Helmet or Fixed Bayonet sort might prove too unsettling for mainstream audiences Warner was courting. Still, this is a more than satisfying update on Burma, and what a welcome sight that wide screen was after years of having it available (if at all) in cropped versions. Sad that Jeff Chandler didn’t get beyond this final performance, dead at only 42 after what I’ve read was a botched operation. Contract players Ty Hardin, Will Hutchins, and Peter Brown were coming to the end of Warner tenures here. This may be their best big-screen work. Hardin is particularly good as second-in-command. Hutchins told us at an autograph show of being flown to the Philippines location one-way, and when scenes were completed, being cut loose without return passage home. Will was on his own. Such was life in WB stables. Merrill’s Marauders represents a last stand for traditional war movies before elephantine excesses (The Longest Day, Battle Of The Bulge) and espionage exotics (Operation Crossbow, The Guns Of Navarone) took hold. If you watched it beside 1956's Attack, you’d think Robert Aldrich's picture came six years later rather than earlier. Were it not for color and scope, Merrill’s Marauders would fit nicely with Air Force, Destination Tokyo, and of course, Objective, Burma, for it would seem to have been made within months of these. Milton Sperling’s United States Pictures banner had flown over a number of Warner recyclings. Distant Drums (1953) was another remake of Objective, Burma he’d produced, this one set in the Everglades. Ownership of Merrill’s Marauders did at least remain with Warners. Most of the other United States negatives passed through various hands and are presently owned by Richard Feiner and Company. Based on the lackluster quality of those released so far on DVD (The Enforcer, Pursued, The Court-Martial Of Billy Mitchell, etc.), I’d say all the elements could use some upgrading.

Merrill’s Marauders was an even then (1962) old-fashioned war movie lacking the sharper edge one expects from renegade director Samuel Fuller. Could Jack Warner have dictated they stick closer to the Objective, Burma model (even to the extent of reusing much of its score)? Credited co-writer and Warner son-in-law Milton Sperling might have subverted Fuller’s customarily hard-bitten approach to combat subjects. This was, after all, a bigger budget show, and off-putting realism of a Steel Helmet or Fixed Bayonet sort might prove too unsettling for mainstream audiences Warner was courting. Still, this is a more than satisfying update on Burma, and what a welcome sight that wide screen was after years of having it available (if at all) in cropped versions. Sad that Jeff Chandler didn’t get beyond this final performance, dead at only 42 after what I’ve read was a botched operation. Contract players Ty Hardin, Will Hutchins, and Peter Brown were coming to the end of Warner tenures here. This may be their best big-screen work. Hardin is particularly good as second-in-command. Hutchins told us at an autograph show of being flown to the Philippines location one-way, and when scenes were completed, being cut loose without return passage home. Will was on his own. Such was life in WB stables. Merrill’s Marauders represents a last stand for traditional war movies before elephantine excesses (The Longest Day, Battle Of The Bulge) and espionage exotics (Operation Crossbow, The Guns Of Navarone) took hold. If you watched it beside 1956's Attack, you’d think Robert Aldrich's picture came six years later rather than earlier. Were it not for color and scope, Merrill’s Marauders would fit nicely with Air Force, Destination Tokyo, and of course, Objective, Burma, for it would seem to have been made within months of these. Milton Sperling’s United States Pictures banner had flown over a number of Warner recyclings. Distant Drums (1953) was another remake of Objective, Burma he’d produced, this one set in the Everglades. Ownership of Merrill’s Marauders did at least remain with Warners. Most of the other United States negatives passed through various hands and are presently owned by Richard Feiner and Company. Based on the lackluster quality of those released so far on DVD (The Enforcer, Pursued, The Court-Martial Of Billy Mitchell, etc.), I’d say all the elements could use some upgrading.

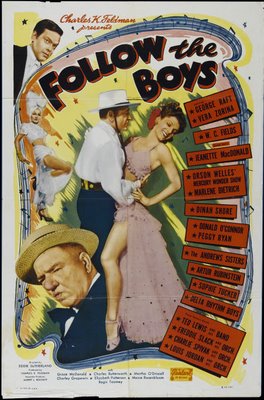

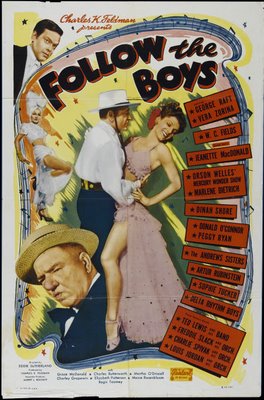

Process screens are rife in Follow The Boys, Universal’s 1944 contribution to the wartime wave of all-star musical revues. We see Donald O’Connor and Peggy Ryan running out to greet what looks to be thousands of GI’s at an outdoor camp stage, only to find themselves cut away to a studio mock-up of the location for their number. What a disappointment Universal didn’t capture that act as it played to the recruits, though it is nice to finally have something of this team on DVD at last. Were it not for Marlene Dietrich’s limited participation, it’s unlikely Follow The Boys would have turned up at all. As it is, we get this as one of eighteen Dietrich features contained in a monster box set recently released in the UK (other selections include rarities Desire, Angel, and the Von Sternberg fave, Shanghai Express). One disturbance here is the running time, a mere 106 minutes. The original ran 122, and though I saw it before at that length, I couldn’t detect anything missing this time. Universal topliners passed on Follow The Boys, thus no Abbott and Costello or Deanna Durbin. We do glimpse Nigel Bruce among a crowd, but no Rathbone (understandable as he was contracted to MGM, and did his Universal Holmes series on loan-outs). Stars like Gloria Jean, Maria Montez, and Evelyn Ankers are shown in pans across rows of silent onlookers at a pep meeting conducted by leading man George Raft. The Lon Chaney shown here (seated behind Sophie Tucker) says not one word and has but this single shot to represent him in the whole of the film. Do also note Orson Welles seated with similarly mute Noah Beery, Jr., with Turhan Bey behind. Welles is a more vocal participant, and gets in his magician act with Dietrich in support. Interesting to see Orson comparatively thin and robust, a dashing figure in top hat and tails, his sleight-of-hand neutralized somewhat by clunky special effects revealing studio artifice behind his "magic." Highlights like this are interspersed with lackluster vaudeville. There’s even an extended dog act presided over by Charles Butterworth. The Andrews Sisters might be anticipated in any Universal show from this period, but again, their act is compromised by an uneasy blend of actual performance and soundstage recreation --- same for Jeannette MacDonald, though she has a nice number in a hospital tent which at least suggests the emotional bond shared by these performers and the servicemen they entertained. Near to the end W.C. Fields saunters into a post canteen to do his pool table routine for what would be the last time. It took Bill just two days to film, despite a schedule allowing for ten. Still, his pacing is slowed. Favored stooge Bill Wolfe walks through unmolested, as if The Great Man had simply forgotten he was there, while subdued laughter from the intercut "audience" is kept to a minimum, possibly on the theory that theatre-goers’ mirth would fill the void. One look at Fields' haggard appearance and you know why he couldn’t get insured for another feature. Still, his routine is what keeps Follow The Boys on radar for hardcore fans today, and if ever we get it released on Region 1, it’ll probably be as part of W.C. Fields --- Volume Three.