John Wayne Learns His Trade

John Wayne Learns His TradeA Ken Maynard Blog-A-Thon is not a likely thing in our Web futures, yet his were the mighty shoulders upon which John Wayne stood when he did a series of six program westerns at Warner Bros. for the 1932-33 season. These are practically unknown today. I only saw them for the first time when TCM began unearthing its treasures. Now the half dozen are on two triple-feature DVD’s from Warner, each title clocking in at around an hour. Wayne himself said that each one was lousier than the last. That may be a harsh judgment, for the lousiness factor is not a cumulative one. There is enough of it spread among the six to disqualify them all from exalted position among Wayne credits, but curiosity value alone places them high on the list for me. Ongoing musical chairs between Maynard's silent stock footage and Wayne's subsequent exploits is a game anyone can enjoy playing. Ken Maynard was a legendary trick rider and rodeo performer who’d been with Ringling Brothers and the Kit Carson Travelling Show through the twenties. He took breaks from these to do independent silent westerns. Ken’s stunt riding was like something out of Greek mythology. His near-total inability to act mattered not a lick. Neither did the epic-scale drinking, for his young constitution could stand abuse, and a few stiff belts only made him braver in the saddle. First-National grabbed Ken for a series in 1926, and legend has it these are among the finest and most actionful of all budget westerns. Front-row kids whooped it up through all eighteen and still remembered them years after the negatives were rotted and junked. Only one survives complete (The Red Raiders). I’d like to think those fans and films are reunited somewhere in a nitrate-based afterlife, for few are left among us who remember Maynard’s silent shows first-hand.

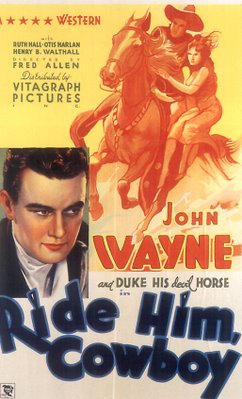

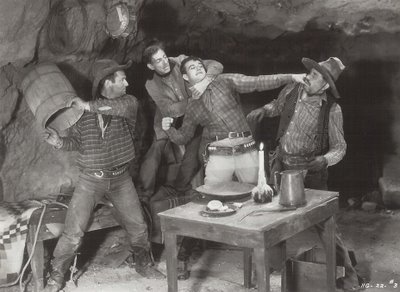

When Warner Bros. took over First-National, they discontinued the westerns. Talkies were initially regarded as incompatible with location work. The idea of merging old footage from the Maynards with new John Wayne programmers was both sound and economical. Ken’s Senor Daredevil had cost $75,000. Wayne’s Ride Him, Cowboy, augmented by the silent action highlights, was completed with a negative cost of $28,000. John Wayne was by all (conflicting) accounts a bargain as well. I’ve read four different figures as to what he was paid, so take your pick --- $125 a week --- $850, or $875, or $1500 per film --- the truth probably lands somewhere in the middle. He was under contract to Warners, having thudded badly with the disappointment of The Big Trail two years previous. Since that woebegone attempt at star making, he’d cast a line into various studio waters, but few seemed willing to risk him in leads. The still shown here is typical of how Warners used Wayne in modern-dress roles. The Life Of Jimmy Dolan was shot concurrently with the westerns, but as with Baby Face, College Coach, and several other 1932 releases, Wayne’s participation was limited to bits and walk-ons. Westerns were for hicks and adolescent boys, a necessary evil to quench the appetites of rural audiences. This would be the arena for John Wayne’s first starring series. His mount was also billed above the title. Duke was alternatively promoted as a Wonder Horse, or a Devil Horse, depending upon his respective disposition. He was also wise as Solomon, displaying remarkable cognitive and reasoning abilities quite beyond the capacity of ordinary steeds. Hey, Duke… Round up the cattle and herd ‘em into the mouth of that canyon! --- and hanged if he doesn’t do just that. On another occasion, Duke seizes the initiative and rings a warning bell in a village under outlaw attack, despite not being privy to uses and purposes of the otherwise unpresupposing instrument. Duke is a common thread through the series. So is Wayne’s mouth organ, or in less suggestive parlance, harmonica, which he plays often and with seeming dexterity.

When Warner Bros. took over First-National, they discontinued the westerns. Talkies were initially regarded as incompatible with location work. The idea of merging old footage from the Maynards with new John Wayne programmers was both sound and economical. Ken’s Senor Daredevil had cost $75,000. Wayne’s Ride Him, Cowboy, augmented by the silent action highlights, was completed with a negative cost of $28,000. John Wayne was by all (conflicting) accounts a bargain as well. I’ve read four different figures as to what he was paid, so take your pick --- $125 a week --- $850, or $875, or $1500 per film --- the truth probably lands somewhere in the middle. He was under contract to Warners, having thudded badly with the disappointment of The Big Trail two years previous. Since that woebegone attempt at star making, he’d cast a line into various studio waters, but few seemed willing to risk him in leads. The still shown here is typical of how Warners used Wayne in modern-dress roles. The Life Of Jimmy Dolan was shot concurrently with the westerns, but as with Baby Face, College Coach, and several other 1932 releases, Wayne’s participation was limited to bits and walk-ons. Westerns were for hicks and adolescent boys, a necessary evil to quench the appetites of rural audiences. This would be the arena for John Wayne’s first starring series. His mount was also billed above the title. Duke was alternatively promoted as a Wonder Horse, or a Devil Horse, depending upon his respective disposition. He was also wise as Solomon, displaying remarkable cognitive and reasoning abilities quite beyond the capacity of ordinary steeds. Hey, Duke… Round up the cattle and herd ‘em into the mouth of that canyon! --- and hanged if he doesn’t do just that. On another occasion, Duke seizes the initiative and rings a warning bell in a village under outlaw attack, despite not being privy to uses and purposes of the otherwise unpresupposing instrument. Duke is a common thread through the series. So is Wayne’s mouth organ, or in less suggestive parlance, harmonica, which he plays often and with seeming dexterity.

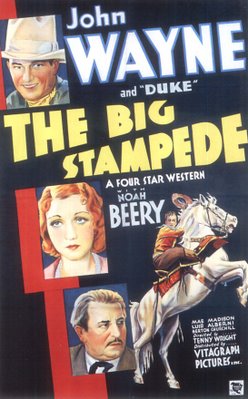

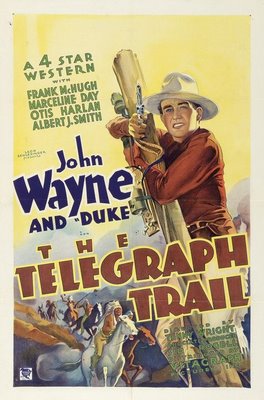

Ride Him, Cowboy was the first. Wayne and Duke share the honors with grainy, undercranked footage of Maynard and his own miracle horse, Tarzan (so named by Edgar Rice Burroughs himself). Whenever Wayne appears to do something truly spectacular, you can rest assured it’s Ken. Maynard insisted that stunts be performed close-up, so the audience would know it was really him. I don’t know how this man kept from getting his fool neck broken. Freeze-frames allow you to spot him in a number of chases and rescues. Wayne dons similar costumes to aid in the deception, but Ken’s easily recognizable when he takes over. They should have paid him that $150, or $850, or whatever. Some fine character actors lend support in these westerns --- Henry B. Walthall’s in two, Noah Beery’s a villain in The Big Stampede, Frank McHugh lends his irritating laugh to Telegraph Trail. Wayne’s labored comedy relief (s) tag along as surely and doggedly as did Porky in Drip-Along Daffy, only he was funny. Love interest is conveyed by way of actresses I’m unacquainted with, but Marceline Day’s in Telegraph Trail, and you may remember her in fetching swim attire as Buster Keaton’s date in The Cameraman.

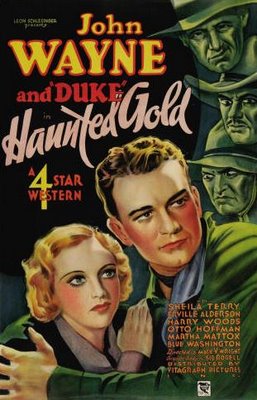

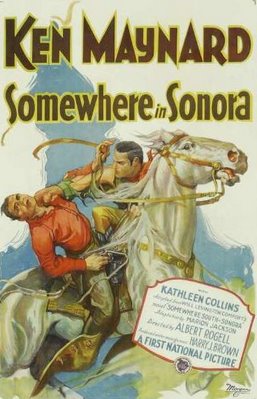

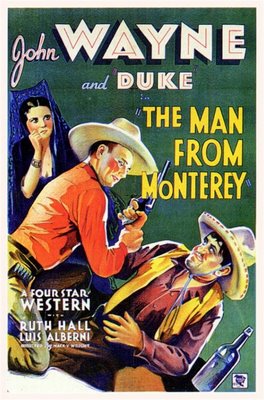

Most of these Waynes were remakes of the Ken Maynards in addition to purloining their stunts (note the posters shown here for both the Maynard and Wayne versions of Somewhere In Sonora). That footage got quite a workout, for it was recycled not only in these, but in a late thirties Dick Foran group as well. John Wayne’s still working through kinks one encounters with any young actor getting his start and training on the job. He’s guileless, fluffs lines occasionally, and gives with a hearty laugh when occasions call for it (and sometimes when they don’t). There are vigorous riding inserts he handles well. Interesting that Wayne shunned horses off-screen, considering the time he spent sitting on their backs. I wonder if he ever regretted being locked into all those westerns. Socializing with John Ford throughout the decade must have been increasingly frustrating, as he was shut out of the man’s pictures for most of that time. I’m sure Wayne was genuinely surprised at being cast in Stagecoach, as by 1939, he’d probably given up on ever working with the director. He was dismissive in later years of these three-day westerns, as he referred to them. Schedules so grueling would have left a bitter taste for anyone charged with maintaining them, but Wayne’s past had a way of revisiting him. Warner Bros. reissued all six of the 1932-33 group in 1940, after Stagecoach catapulted the actor to "A" status, and one of them, Haunted Gold, was actually back in theatres for some 1962 bookings. Cheap westerns were that way because the profit margin was thin as a razor’s edge, though Wayne’s Warner group performed well in comparison with Poverty Row quickies and their State’s Rights distribution. Ride Him, Cowboy, remade from a Maynard silent of only six years before, took $93,970 in domestic rentals, and $60,000 foreign. Against those negative costs of $28,000, it ended $67,478 to the good. The average profit for the series was $60,912. Wayne left after that first season, however. Maybe Warners wasn’t interested in a second frame, or could be the money was better with Nat Levine and his serials (Wayne did three of them). Quality on these new DVD's is outstanding, by the way. You seldom see "B" westerns looking this good. I hope the triple-feature concept is something Warners will continue exploring, as it seems a congenial format for series titles they own. Nancy Drew, Perry Mason, Dick Foran, Tim Holt and George O’Brien RKO westerns, The Falcon, The Saint, Andy Hardy, Torchy Blaine, Dr. Kildare, Maisie --- am I overlooking any?