Just A Small AnnouncementOwing to what I’m told has been excessive posting and obsessive attention to Greenbriar Picture Shows (since when is every waking hour obsessive attention?), we are obliged to modify the killing pace that’s been maintained since day one, and cut back to two or so stories a week as opposed to showing up with something new every time the cock crows. That’s not to say that Greenbriar is closing its doors. By no means. There are several features in the pipeline now, and many more to come. It’s just those silly things like sleep and getting outdoors occasionally that interfere with the really important business of feeding this webpage. Most of my blogging peers, many of whom are listed on the Greenbriar links page, have the good sense to maintain balance along with a high standard of quality in what they contribute, and they’re examples worth following. As for the Monday Glamour Starters, they will continue, though not necessarily on Mondays, and not on a weekly schedule. On the topic of outstanding sites, there’s a new one that has been dazzling me on a near daily basis for several weeks now. Vitaphone Varieties is devoted to the early days of sound, with articles and research that are breathtaking in their detail and erudition. Jeff Cohen is the host, and he’s got info/images I’ve never seen anyplace else. Go there and get some serious film history!

Just A Small AnnouncementOwing to what I’m told has been excessive posting and obsessive attention to Greenbriar Picture Shows (since when is every waking hour obsessive attention?), we are obliged to modify the killing pace that’s been maintained since day one, and cut back to two or so stories a week as opposed to showing up with something new every time the cock crows. That’s not to say that Greenbriar is closing its doors. By no means. There are several features in the pipeline now, and many more to come. It’s just those silly things like sleep and getting outdoors occasionally that interfere with the really important business of feeding this webpage. Most of my blogging peers, many of whom are listed on the Greenbriar links page, have the good sense to maintain balance along with a high standard of quality in what they contribute, and they’re examples worth following. As for the Monday Glamour Starters, they will continue, though not necessarily on Mondays, and not on a weekly schedule. On the topic of outstanding sites, there’s a new one that has been dazzling me on a near daily basis for several weeks now. Vitaphone Varieties is devoted to the early days of sound, with articles and research that are breathtaking in their detail and erudition. Jeff Cohen is the host, and he’s got info/images I’ve never seen anyplace else. Go there and get some serious film history!

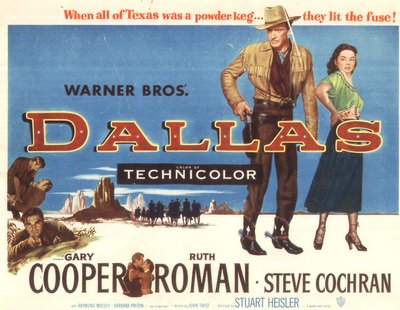

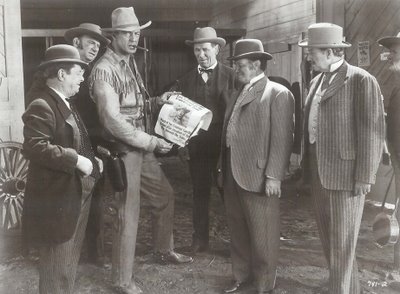

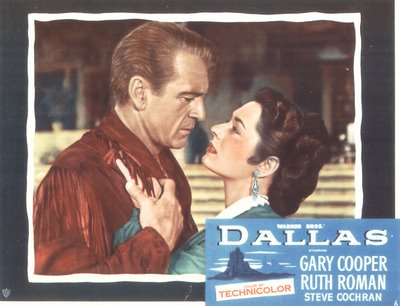

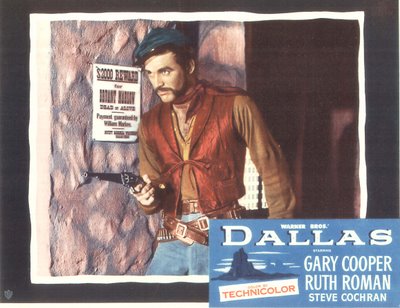

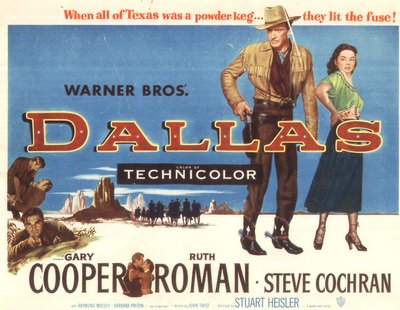

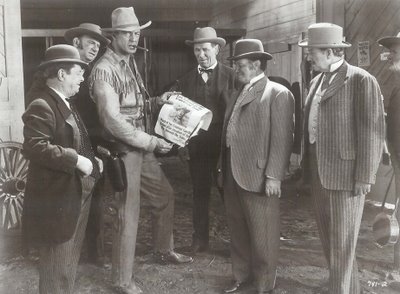

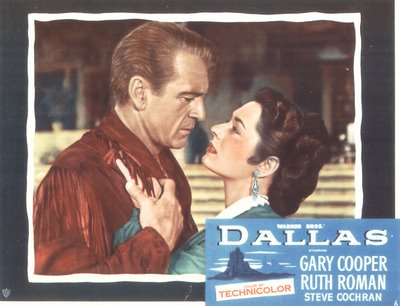

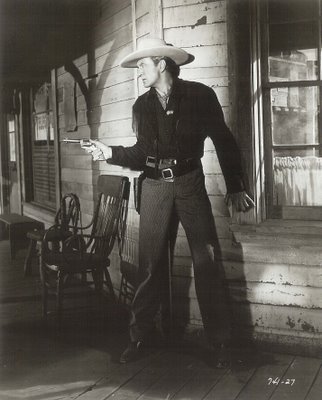

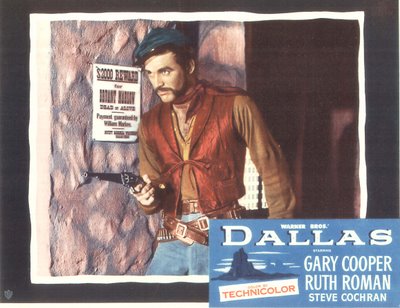

Of Dallas and Comfort WesternsIt must have come as quite a shock when Gary Cooper received the script for his fourth starring vehicle under the Warner's contract he'd signed in 1948. After three classy features (The Fountainhead, Task Force, and Bright Leaf) with first-rate directors (King Vidor, Delmer Daves, and Michael Curtiz), Dallas was a distinct comedown. It had been announced for Errol Flynn, but Cooper was assigned at the eleventh hour. The studio's choice of journeyman Stuart Heisler to direct was hardly a vote of confidence. If you look at Cooper's gag cameo in the previous year's It's A Great Feeling, you get a pretty good idea of how his new employers regarded the star. The appearance is brief --- Cooper is carelessy photographed (at a time when age was starting to betray him), and the exchange with Dennis Morgan trades on old yup and nope routines that had dogged him since the beginning of his career. Two decades of fine performances had taken Cooper way beyond that insulting cliche, yet here he was, engaging in self-parody that had to rankle. To some extent, Dallas is more of the same. There is Technicolor, though it doesn't flatter him (in 16mm, his hair looked almost orange at times, even on original dye-transfer prints), and the whole thing has a slapdash, backlot feel about it. So my recommendation? You must get this movie! It's practically a textbook on the declining careers of a pre-war generation of great leading men, that fallow period during the late forties when youngsters like Gregory Peck, Burt Lancaster, and Robert Mitchum were getting the really interesting parts, while veteran stars---Gable, Flynn, Cooper --- were having to get by in studio product with no allowance made for changing times, or the leading man's advancing age(s). Gary Cooper is fabulous in Dallas, giving his best to a bad job. He's winging dialogue, peppering dull scenes with quirky mannerisms; in short, making plenty out of nothing --- getting a lemon, and giving us lemonade. Watch for his introductory scene --- it's a classic --- and only Cooper could make it look so good; burning that wanted poster and lighting his cigar --- great. The leading lady is Ruth Roman --- I guess that's where Warners saved some money. After all, Coop didn't come cheap. For the record, Dallas had a negative cost of 1.390 million (significantly below the money spent on his previous WB's), and final worldwide rentals were 4.490 million, so Cooper in a western was still boxoffice. Too bad WB didn't think enough of him to put a little more effort into the piece. I still love it though, and what a kick to see Raymond Massey in a seedy land-grabber villain role (and Steve Cochran's his brother!). Bet Massey loved telling that one to his lunch companions at the Player's Club. Barbara Payton's there too. Read her sleazy auto-bio, watch this movie, and think about it. There's lots to like in Dallas --- a wonderful Max Steiner score --- Cooper masquerading as a "dude" --- and a sock finish when he finally corners Massey. High Noon was a year away, but you could argue this one’s more fun….

Of Dallas and Comfort WesternsIt must have come as quite a shock when Gary Cooper received the script for his fourth starring vehicle under the Warner's contract he'd signed in 1948. After three classy features (The Fountainhead, Task Force, and Bright Leaf) with first-rate directors (King Vidor, Delmer Daves, and Michael Curtiz), Dallas was a distinct comedown. It had been announced for Errol Flynn, but Cooper was assigned at the eleventh hour. The studio's choice of journeyman Stuart Heisler to direct was hardly a vote of confidence. If you look at Cooper's gag cameo in the previous year's It's A Great Feeling, you get a pretty good idea of how his new employers regarded the star. The appearance is brief --- Cooper is carelessy photographed (at a time when age was starting to betray him), and the exchange with Dennis Morgan trades on old yup and nope routines that had dogged him since the beginning of his career. Two decades of fine performances had taken Cooper way beyond that insulting cliche, yet here he was, engaging in self-parody that had to rankle. To some extent, Dallas is more of the same. There is Technicolor, though it doesn't flatter him (in 16mm, his hair looked almost orange at times, even on original dye-transfer prints), and the whole thing has a slapdash, backlot feel about it. So my recommendation? You must get this movie! It's practically a textbook on the declining careers of a pre-war generation of great leading men, that fallow period during the late forties when youngsters like Gregory Peck, Burt Lancaster, and Robert Mitchum were getting the really interesting parts, while veteran stars---Gable, Flynn, Cooper --- were having to get by in studio product with no allowance made for changing times, or the leading man's advancing age(s). Gary Cooper is fabulous in Dallas, giving his best to a bad job. He's winging dialogue, peppering dull scenes with quirky mannerisms; in short, making plenty out of nothing --- getting a lemon, and giving us lemonade. Watch for his introductory scene --- it's a classic --- and only Cooper could make it look so good; burning that wanted poster and lighting his cigar --- great. The leading lady is Ruth Roman --- I guess that's where Warners saved some money. After all, Coop didn't come cheap. For the record, Dallas had a negative cost of 1.390 million (significantly below the money spent on his previous WB's), and final worldwide rentals were 4.490 million, so Cooper in a western was still boxoffice. Too bad WB didn't think enough of him to put a little more effort into the piece. I still love it though, and what a kick to see Raymond Massey in a seedy land-grabber villain role (and Steve Cochran's his brother!). Bet Massey loved telling that one to his lunch companions at the Player's Club. Barbara Payton's there too. Read her sleazy auto-bio, watch this movie, and think about it. There's lots to like in Dallas --- a wonderful Max Steiner score --- Cooper masquerading as a "dude" --- and a sock finish when he finally corners Massey. High Noon was a year away, but you could argue this one’s more fun….

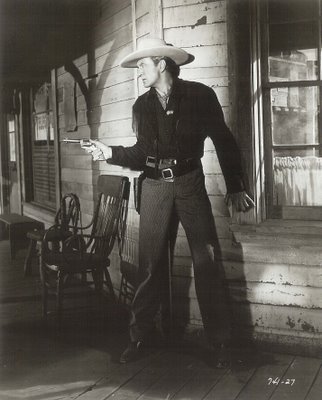

Cooper no doubt wondered when a Broken Arrow or The Gunfighter might arrive to rescue his western prospects, but for stars too high-priced, if not overly typed , these bolder projects seemed denied. Warners found it simpler, and more lucrative, to continue on autopilot with increasingly formula vehicles along the lines of Dallas (1.9 million profit), Distant Drums (2.2, one of WB’s biggest that year), and Springfield Rifle (1.3). What’s the sense of challenging the Cooper audience with thoughtful scripts when these were pulling such figures? Dallas is really little more than a variation on the Randolph Scott model, and those were being turned out two to three a year by directors no more inspired than Stuart Heisler. It works, as little care seems to have been applied, so unlike pretentious westerns of the Broken Arrow school, it’s loopier and more unpredictable. Dialogue comes out of left field. You don’t get a sense of anyone looking over writer’s shoulders. What’s at stake when you know the fans will be there in any case? Cooper’s less inhibited and more willing to fall back on old tricks. Dallas gives full vent to his way with breaking up lines, flexing trigger-fingers, and doing that showdown walk reserved for westerns he couldn’t otherwise take seriously. Confusion over whether Dallas was serious or send-up merely enhances the fun, for Cooper seems to have come in some days willing enough to play straight, while on others he’s back in Along Came Jones mode, less self-consciously this time and all the better for it. You can’t help feeling sorry for Raymond Massey, though. There’s one agonizing scene where they put him on horseback --- a real horse --- and the man looks terrified. Only two years previous, he’s wearing three-piece suits behind the owner’s desk at The New York Banner, and now this (but worse was yet to come, for within a few months, he’d be tangling with Randolph Scott in Sugarfoot!).

Cooper no doubt wondered when a Broken Arrow or The Gunfighter might arrive to rescue his western prospects, but for stars too high-priced, if not overly typed , these bolder projects seemed denied. Warners found it simpler, and more lucrative, to continue on autopilot with increasingly formula vehicles along the lines of Dallas (1.9 million profit), Distant Drums (2.2, one of WB’s biggest that year), and Springfield Rifle (1.3). What’s the sense of challenging the Cooper audience with thoughtful scripts when these were pulling such figures? Dallas is really little more than a variation on the Randolph Scott model, and those were being turned out two to three a year by directors no more inspired than Stuart Heisler. It works, as little care seems to have been applied, so unlike pretentious westerns of the Broken Arrow school, it’s loopier and more unpredictable. Dialogue comes out of left field. You don’t get a sense of anyone looking over writer’s shoulders. What’s at stake when you know the fans will be there in any case? Cooper’s less inhibited and more willing to fall back on old tricks. Dallas gives full vent to his way with breaking up lines, flexing trigger-fingers, and doing that showdown walk reserved for westerns he couldn’t otherwise take seriously. Confusion over whether Dallas was serious or send-up merely enhances the fun, for Cooper seems to have come in some days willing enough to play straight, while on others he’s back in Along Came Jones mode, less self-consciously this time and all the better for it. You can’t help feeling sorry for Raymond Massey, though. There’s one agonizing scene where they put him on horseback --- a real horse --- and the man looks terrified. Only two years previous, he’s wearing three-piece suits behind the owner’s desk at The New York Banner, and now this (but worse was yet to come, for within a few months, he’d be tangling with Randolph Scott in Sugarfoot!).

High Noon (an outside picture) might have turned the tide at anyone else’s home studio, but Warners saw no reason to elevate Cooper toward more challenging work --- thus there was Blowing Wild, which had him hauling nitro and shunning Barbara Stanwyck. Opening sequences are near identical to Treasure Of the Sierra Madre, as though some of that quality might rub off. I’m only sorry Warners no longer owns this negative, for it would make a great addition to The Gary Cooper Collection --- Volume Two. Dallas is happily available however, and don’t let anyone kid you it’s among the lesser offerings. Any western that pairs Steve Cochran and Barbara Payton as desperado lovebirds has to be getting something right, even if unknowingly. I understand the two frequently repaired to remote corners of the backlot for R&R. This I would expect from Cochran/Payton, but where was Coop? Surely he exercised a leading man’s prior claim, and my understanding of B.P. suggests she’d have been more than willing, as even model of rectitude Gregory Peck succumbed to her charms when they made Only The Valiant a year later. There’s a major biography of Barbara Payton forthcoming, and the author’s website includes a sample chapter. Based on that, it should be definitive. In the end, I’d imagine Dallas to be the sort of commonplace western Dean Martin used to watch on his television instead of going out with Frank and the boys. No academic will write monographs about this one. It’s the ideal respite from intellectual and emotional demands made by The Searchers and The Wild Bunch, as one’s own advancing age makes these seem somehow more oppressive. I used to wonder why middle-aged men sitting in front of the tube made no distinction between a John Ford and an Audie Murphy. Now at least it seems a little clearer. I’d never have interrogated my father with regards the aesthetic gulf between Red River and an episode of Wagon Train. Dallas and Audie and the lesser Scotts entertain without imposing, and that’s well enough for those men who prefer enjoying their westerns without being turned inside out.

High Noon (an outside picture) might have turned the tide at anyone else’s home studio, but Warners saw no reason to elevate Cooper toward more challenging work --- thus there was Blowing Wild, which had him hauling nitro and shunning Barbara Stanwyck. Opening sequences are near identical to Treasure Of the Sierra Madre, as though some of that quality might rub off. I’m only sorry Warners no longer owns this negative, for it would make a great addition to The Gary Cooper Collection --- Volume Two. Dallas is happily available however, and don’t let anyone kid you it’s among the lesser offerings. Any western that pairs Steve Cochran and Barbara Payton as desperado lovebirds has to be getting something right, even if unknowingly. I understand the two frequently repaired to remote corners of the backlot for R&R. This I would expect from Cochran/Payton, but where was Coop? Surely he exercised a leading man’s prior claim, and my understanding of B.P. suggests she’d have been more than willing, as even model of rectitude Gregory Peck succumbed to her charms when they made Only The Valiant a year later. There’s a major biography of Barbara Payton forthcoming, and the author’s website includes a sample chapter. Based on that, it should be definitive. In the end, I’d imagine Dallas to be the sort of commonplace western Dean Martin used to watch on his television instead of going out with Frank and the boys. No academic will write monographs about this one. It’s the ideal respite from intellectual and emotional demands made by The Searchers and The Wild Bunch, as one’s own advancing age makes these seem somehow more oppressive. I used to wonder why middle-aged men sitting in front of the tube made no distinction between a John Ford and an Audie Murphy. Now at least it seems a little clearer. I’d never have interrogated my father with regards the aesthetic gulf between Red River and an episode of Wagon Train. Dallas and Audie and the lesser Scotts entertain without imposing, and that’s well enough for those men who prefer enjoying their westerns without being turned inside out.

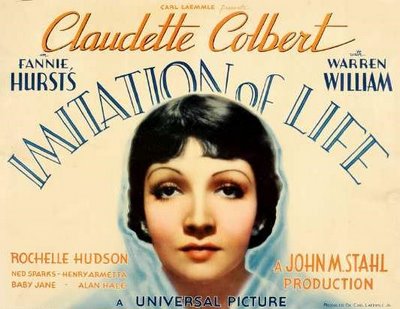

Monday Glamour Starter --- Claudette Colbert

Monday Glamour Starter --- Claudette Colbert

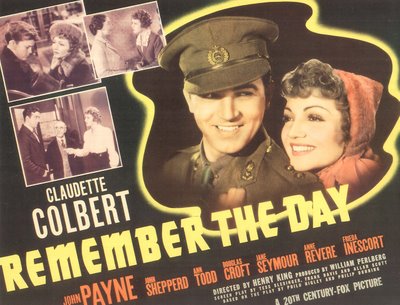

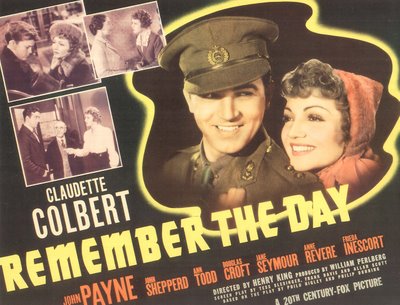

I was in the Washington, D.C. airport about twenty years ago when an announcement came over the loud speakers --- Would Miss Claudette Colbert please come to the information desk? I stopped cold in my tracks, much as John Sheppard/Shepperd Strudwick did in Remember The Day (Miss Trinell!). Was I hearing things? No, they repeated it. Miss Claudette Colbert, please come to the information counter. Having my own plane to catch, what could I do? To this day, there’s no doubt in my mind it was she they were calling. I mean, how many Claudette Colberts could there be? Had that announcement come forty years earlier, there would have been a mass exodus toward that counter. I have to assume the attendant had no idea whom she was addressing. But here’s the remarkable thing --- Claudette Colbert was working at the time --- back on the boards with Rex Harrison after she’d passed eighty. It’s not as though she needed the money, for there was plenty of that, plus an estate in Barbados. If they’d passed out ribbons for Smartest Actress in the Golden Age biz, Claudette would have surely collected, for she never put a foot wrong. Success was mostly followed by greater success, and she enjoyed 92 years of it. Why can’t they all end up like this?

I was in the Washington, D.C. airport about twenty years ago when an announcement came over the loud speakers --- Would Miss Claudette Colbert please come to the information desk? I stopped cold in my tracks, much as John Sheppard/Shepperd Strudwick did in Remember The Day (Miss Trinell!). Was I hearing things? No, they repeated it. Miss Claudette Colbert, please come to the information counter. Having my own plane to catch, what could I do? To this day, there’s no doubt in my mind it was she they were calling. I mean, how many Claudette Colberts could there be? Had that announcement come forty years earlier, there would have been a mass exodus toward that counter. I have to assume the attendant had no idea whom she was addressing. But here’s the remarkable thing --- Claudette Colbert was working at the time --- back on the boards with Rex Harrison after she’d passed eighty. It’s not as though she needed the money, for there was plenty of that, plus an estate in Barbados. If they’d passed out ribbons for Smartest Actress in the Golden Age biz, Claudette would have surely collected, for she never put a foot wrong. Success was mostly followed by greater success, and she enjoyed 92 years of it. Why can’t they all end up like this?

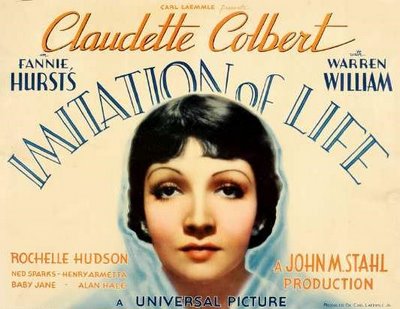

Did those mid-eighties audiences realize they were watching a sixty-year veteran of the stage? Colbert started on Broadway. She was one of its leading lights when talkies came calling. There was hesitation, owing to a bad experience with a single silent feature under Frank Capra’s direction (For the Love Of Mike). Legit having been largely wiped out by depression, she, like a lot of New Yorkers, took the Hollywood offer and tried again. For Colbert, it began with films at Astoria. She’d been raised in Gotham, though born in France. Her domineering mother maintained a strict household, addressing the children only in native tongue, which prepared Claudette to lend assist when Paramount needed French-language versions of The Big Pond and Slightly Scarlet. Early roles were along conventional paths --- her roles were interchangeable with Sylvia Sidney, Miriam Hopkins, Carole Lombard, Nancy Carroll (whom she resembled) --- how do you distinguish yourself in a bakery window filled with near identical sweets? For each step forward (The Smiling Lieutenant), there were three back (Secrets Of A Secretary). Getting noticed on assembly lines was never easy, yet this was an actress with authority none of the rest approached. Go listen to Colbert read lines in that excellent pre-code Torch Singer (if you can find it). Nobody handles dialogue so well. Apparently, it came easy. She knew she’d score from early on, and didn’t mind saying so. It wasn’t conceit … just a fact of (her) life. Acting is instinctive … either you have it or you don’t. Well, she had it in spades, and bore down from the get-go on employers who imagined they could dictate terms. Not only did Colbert get into serious money fast ($5000 a week by 1934), she took charge as well of make-up application and costume selection (and why not? --- she’d trained in commercial art at school and originally sought a career in fashion design). Hell On Wheels was how they described her, but so what when you’re right?

Did those mid-eighties audiences realize they were watching a sixty-year veteran of the stage? Colbert started on Broadway. She was one of its leading lights when talkies came calling. There was hesitation, owing to a bad experience with a single silent feature under Frank Capra’s direction (For the Love Of Mike). Legit having been largely wiped out by depression, she, like a lot of New Yorkers, took the Hollywood offer and tried again. For Colbert, it began with films at Astoria. She’d been raised in Gotham, though born in France. Her domineering mother maintained a strict household, addressing the children only in native tongue, which prepared Claudette to lend assist when Paramount needed French-language versions of The Big Pond and Slightly Scarlet. Early roles were along conventional paths --- her roles were interchangeable with Sylvia Sidney, Miriam Hopkins, Carole Lombard, Nancy Carroll (whom she resembled) --- how do you distinguish yourself in a bakery window filled with near identical sweets? For each step forward (The Smiling Lieutenant), there were three back (Secrets Of A Secretary). Getting noticed on assembly lines was never easy, yet this was an actress with authority none of the rest approached. Go listen to Colbert read lines in that excellent pre-code Torch Singer (if you can find it). Nobody handles dialogue so well. Apparently, it came easy. She knew she’d score from early on, and didn’t mind saying so. It wasn’t conceit … just a fact of (her) life. Acting is instinctive … either you have it or you don’t. Well, she had it in spades, and bore down from the get-go on employers who imagined they could dictate terms. Not only did Colbert get into serious money fast ($5000 a week by 1934), she took charge as well of make-up application and costume selection (and why not? --- she’d trained in commercial art at school and originally sought a career in fashion design). Hell On Wheels was how they described her, but so what when you’re right?

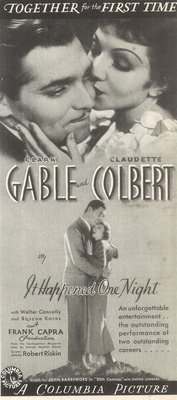

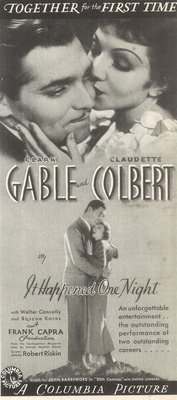

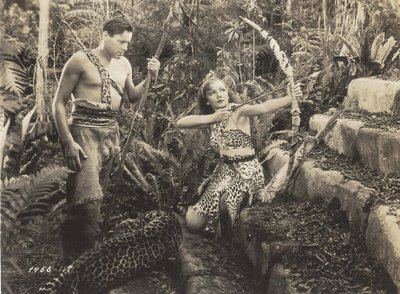

Absurd costume parts were not her strength, but they didn’t intimidate her. Playing Sign Of The Cross and Cleopatra modern seemed as good a way as any to deflect embarrassment. You could take her straight or imagine she’s sending the whole thing up. Either way was satisfying. The one that conferred immortality was It Happened One Night. I’ll depart from standard orthodoxy where this show is concerned, and chances are you know what I’m referring to: Nobody wanted to do it … Gable in the doghouse and being punished by Metro … Colbert slumming on Poverty Row, etc. All this made for good columns after smash ticket sales plus clean sweep of Academy Awards, and published histories have carried the legend forward in lock-step since, but I’ve never bought into IHON's too pat rags-to-riches tale. For starters, Capra was a recognized major talent before It Happened One Night. He’d done Flight, Dirigible, The Miracle Woman, Platinum Blonde, American Madness, Lady For A Day --- all well received and critically well-regarded. How could any project under his direction be regarded a step down? I think a lot of this was Capra’s own myth-making helped in no small way by thirty or so years passed between the film’s release and his autobiography, together with willingness on the part of latter-day interviewers to accept FC's colorful revisions without question. One thing’s sure --- Claudette Colbert was difficult on the set, but that would have been case in any event, owing to increased clout and willingness to exercise a star’s prerogative. It Happened One Night might have proved a mixed blessing, for both she and Gable were fated to revisit this formula in any number of less inspired retreads as a decade wore on --- madcap heiresses and cocksure reporters becoming increasingly unwelcome as producers sought to make it all happen just one more night.

Absurd costume parts were not her strength, but they didn’t intimidate her. Playing Sign Of The Cross and Cleopatra modern seemed as good a way as any to deflect embarrassment. You could take her straight or imagine she’s sending the whole thing up. Either way was satisfying. The one that conferred immortality was It Happened One Night. I’ll depart from standard orthodoxy where this show is concerned, and chances are you know what I’m referring to: Nobody wanted to do it … Gable in the doghouse and being punished by Metro … Colbert slumming on Poverty Row, etc. All this made for good columns after smash ticket sales plus clean sweep of Academy Awards, and published histories have carried the legend forward in lock-step since, but I’ve never bought into IHON's too pat rags-to-riches tale. For starters, Capra was a recognized major talent before It Happened One Night. He’d done Flight, Dirigible, The Miracle Woman, Platinum Blonde, American Madness, Lady For A Day --- all well received and critically well-regarded. How could any project under his direction be regarded a step down? I think a lot of this was Capra’s own myth-making helped in no small way by thirty or so years passed between the film’s release and his autobiography, together with willingness on the part of latter-day interviewers to accept FC's colorful revisions without question. One thing’s sure --- Claudette Colbert was difficult on the set, but that would have been case in any event, owing to increased clout and willingness to exercise a star’s prerogative. It Happened One Night might have proved a mixed blessing, for both she and Gable were fated to revisit this formula in any number of less inspired retreads as a decade wore on --- madcap heiresses and cocksure reporters becoming increasingly unwelcome as producers sought to make it all happen just one more night.

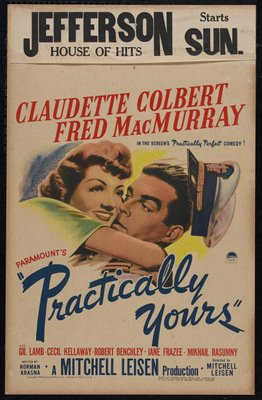

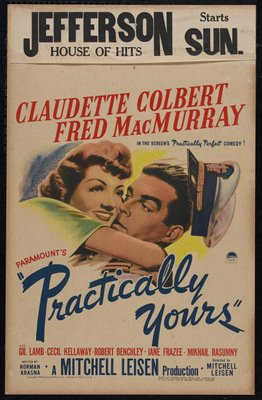

Another tall story may be this business about Colbert’s refusal to be photographed from the right side. No doubt there’s some truth in it, but sets rebuilt? I mean, torn down and rebuilt? Did anyone have that much juice during the studio era? Probably another of those long-bearded press agent fabs that somehow transitioned into primary resource for writers all too willing to believe what they read in Hedda Hopper’s old dailies. Colbert was carefully photographed. She saw to that. They say this actress understood a camera better than Dietrich. Again, she likely knew best, for having remained seemingly ageless if nothing else. Her own explanation cited an avoidance of standard vices, and you can add the sun to this list. She stayed away from that and never wrinkled. Others did not and ended up looking like Randy Scott’s old saddlebag. Mother parts she embraced early on, unafflicted with (apx.) same-age Norma Shearer’s vanity in that respect (N.S. having turned down both Now, Voyager and Mrs. Miniver because she was "too young" for such roles). Since You Went Away was most triumphant of these, but there was other outstanding work during those apex years of the late thirties/early forties. She aged onscreen as Remember The Day’s lifelong schoolmarm. If there’s a better performance than hers in this, I’ve not seen it. Fox Movie Channel schedules R.T.D. often. Watch it next time. You’ll break down in tears. Fantastic movie. Then there’s Drums Along the Mohawk, grim, but a John Ford masterpiece. There’s a DVD of that. The Palm Beach Story is one of the better Preston Sturges comedies. Wish she’d done more of them. All those Paramount laffers with Fred MacMurray appear to be buried deep as Ramses’ tomb, but hope springs eternal that present owner Universal will unearth them. No Time For Love is among the funnier of these, but none are without interest. By 1945, Colbert would be out of Paramount and free-lancing. Her price? --- $150,000 per picture. Her motivation to work? --- probably not considerable, since she’d married well (a second time, to a prominent doctor). Her social life combined Hollywood’s elite with the richest among L.A.’s medical community. Colbert was becoming a social lioness if not a continuing boxoffice lure. The late forties saw the initial decline. Sometimes she got lucky in a fluke like The Egg and I, but that one hit because it introduced the Kettles (as in Ma and Pa), who’d go on to popularity eclipsing even Colbert’s. By now, she was noticed as much for parts she lost as ones she took. State Of The Union was a final clash with Capra. Such were Colbert’s demands that he finally replaced her with Katherine Hepburn. All About Eve was written with her in mind, but a back injury performing stunts (!) in Three Came Home paved the way for Bette Davis to move in and give perhaps her finest performance. The loss would rankle Colbert for the rest of her life, as there were no more offers so promising as this. Television was a port of call throughout the fifties. She even touted Maxwell House coffee on the small screen, but not from hunger. Work remained, as it had always been, something to keep her busy, though she’d acknowledge regret for not having been more aggressive in seeking better projects. DeMille offered The Ten Commandments, but was turned down (to do Ford Star Jubilee instead?). After playing Troy Donahue’s mother in Parrish, she hung it up on features (well, how do you top that?). Pleas for memoirs were ignored. What’s so interesting about my life?, she’d ask, and based on the common-sense way she’d lived it, maybe not much, at least in the way of scandal and sensation. Producers still wanted her. Much of the fan mail came from young people. Ross Hunter noticed and tried to induce her to join the Airport ensemble, but no dice. The surprise eighties reemergence found her back on the stage where she’d begun, skills undiminished, and a wider audience got a last look in a 1987 TV movie, The Two Mrs. Grenvilles. She died in 1996.Photo CaptionsClaudette Colbert with Maurice Chevalier in The Smiling LieutenantParamount Exhibitor Manual PortraitClaudette as CleopatraImitation Of Life Title CardIt Happened One Night AdWith Herbert Marshall in Four Frightened PeopleWith Henry Fonda in Drums Along The MohawkTitle Card from Remember The DayWith Joel McCrea and Rudy Vallee in The Palm Beach StoryWindow Card from Practically YoursParamount Publicity PortaritWith Jennifer Jones and Shirley Temple in Since You Went Away

Another tall story may be this business about Colbert’s refusal to be photographed from the right side. No doubt there’s some truth in it, but sets rebuilt? I mean, torn down and rebuilt? Did anyone have that much juice during the studio era? Probably another of those long-bearded press agent fabs that somehow transitioned into primary resource for writers all too willing to believe what they read in Hedda Hopper’s old dailies. Colbert was carefully photographed. She saw to that. They say this actress understood a camera better than Dietrich. Again, she likely knew best, for having remained seemingly ageless if nothing else. Her own explanation cited an avoidance of standard vices, and you can add the sun to this list. She stayed away from that and never wrinkled. Others did not and ended up looking like Randy Scott’s old saddlebag. Mother parts she embraced early on, unafflicted with (apx.) same-age Norma Shearer’s vanity in that respect (N.S. having turned down both Now, Voyager and Mrs. Miniver because she was "too young" for such roles). Since You Went Away was most triumphant of these, but there was other outstanding work during those apex years of the late thirties/early forties. She aged onscreen as Remember The Day’s lifelong schoolmarm. If there’s a better performance than hers in this, I’ve not seen it. Fox Movie Channel schedules R.T.D. often. Watch it next time. You’ll break down in tears. Fantastic movie. Then there’s Drums Along the Mohawk, grim, but a John Ford masterpiece. There’s a DVD of that. The Palm Beach Story is one of the better Preston Sturges comedies. Wish she’d done more of them. All those Paramount laffers with Fred MacMurray appear to be buried deep as Ramses’ tomb, but hope springs eternal that present owner Universal will unearth them. No Time For Love is among the funnier of these, but none are without interest. By 1945, Colbert would be out of Paramount and free-lancing. Her price? --- $150,000 per picture. Her motivation to work? --- probably not considerable, since she’d married well (a second time, to a prominent doctor). Her social life combined Hollywood’s elite with the richest among L.A.’s medical community. Colbert was becoming a social lioness if not a continuing boxoffice lure. The late forties saw the initial decline. Sometimes she got lucky in a fluke like The Egg and I, but that one hit because it introduced the Kettles (as in Ma and Pa), who’d go on to popularity eclipsing even Colbert’s. By now, she was noticed as much for parts she lost as ones she took. State Of The Union was a final clash with Capra. Such were Colbert’s demands that he finally replaced her with Katherine Hepburn. All About Eve was written with her in mind, but a back injury performing stunts (!) in Three Came Home paved the way for Bette Davis to move in and give perhaps her finest performance. The loss would rankle Colbert for the rest of her life, as there were no more offers so promising as this. Television was a port of call throughout the fifties. She even touted Maxwell House coffee on the small screen, but not from hunger. Work remained, as it had always been, something to keep her busy, though she’d acknowledge regret for not having been more aggressive in seeking better projects. DeMille offered The Ten Commandments, but was turned down (to do Ford Star Jubilee instead?). After playing Troy Donahue’s mother in Parrish, she hung it up on features (well, how do you top that?). Pleas for memoirs were ignored. What’s so interesting about my life?, she’d ask, and based on the common-sense way she’d lived it, maybe not much, at least in the way of scandal and sensation. Producers still wanted her. Much of the fan mail came from young people. Ross Hunter noticed and tried to induce her to join the Airport ensemble, but no dice. The surprise eighties reemergence found her back on the stage where she’d begun, skills undiminished, and a wider audience got a last look in a 1987 TV movie, The Two Mrs. Grenvilles. She died in 1996.Photo CaptionsClaudette Colbert with Maurice Chevalier in The Smiling LieutenantParamount Exhibitor Manual PortraitClaudette as CleopatraImitation Of Life Title CardIt Happened One Night AdWith Herbert Marshall in Four Frightened PeopleWith Henry Fonda in Drums Along The MohawkTitle Card from Remember The DayWith Joel McCrea and Rudy Vallee in The Palm Beach StoryWindow Card from Practically YoursParamount Publicity PortaritWith Jennifer Jones and Shirley Temple in Since You Went Away

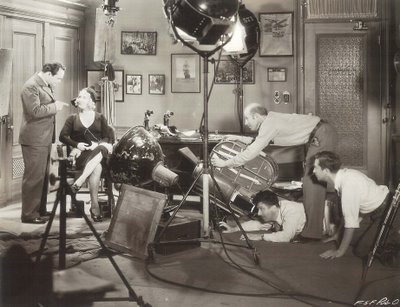

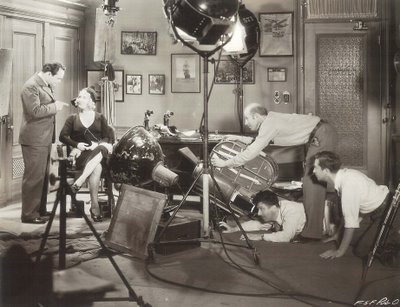

Warner Workdays and Frances Dee's Birthday They say crews at Warner Bros., sometimes worked around the clock in the early thirties. Pictures that would take months to shoot today were wrapped up in weeks back then. Five Star Final is the show in progress here. Director Mervyn LeRoy is lining up an imaginative angle on star Edward G. Robinson. Chances are they’ve been at it for the last eighteen hours. Every interview I’ve read with Warner players talked about those grueling hours. Unions were not yet an effective industry force; thus stages kept humming right through the nights and many weekends as well.

They say crews at Warner Bros., sometimes worked around the clock in the early thirties. Pictures that would take months to shoot today were wrapped up in weeks back then. Five Star Final is the show in progress here. Director Mervyn LeRoy is lining up an imaginative angle on star Edward G. Robinson. Chances are they’ve been at it for the last eighteen hours. Every interview I’ve read with Warner players talked about those grueling hours. Unions were not yet an effective industry force; thus stages kept humming right through the nights and many weekends as well.

On the topic of birthdays, this is year 97 since Frances Dee was born, and here she’s immersed in a fishpond located in front of Paramount’s administration building around 1932. Dee was a frequent guest at Cinecons until just a few years before her death in 2004. Her performance in Blood Money is one amazing Pre-Code exhibition. Too bad it's out of circulation today, but then, so are other good ones featuring Frances Dee --- King Of The Jungle, Murders In The Zoo, An American Tragedy. What a pre-code box Universal could gather if they were so inclined. Their recent Preston Sturges Collection is a step in the right direction. So is the forthcoming release of The Heiress and Arabian Nights. Could 2007 be the year Universal commits to classics on DVD?

Jack Benny's Making His ListSome of us are getting Christmas shopping underway this weekend, so it seemed as good a time as any to pass along one of Jack Benny’s ideas for gift giving. How could Jack have known back in the forties (?) how controversial that carton of Luckies would become in any number of households within a few decades? I just read about one town where they’ve outlawed smoking in homes. Wonder how Benny would have reacted to a headline like that! He’s certainly laid in a supply, and among the list of recipients, I do recognize George Burns, Gracie Allen, and --- is that Merle Oberon’s name? His neat little miniature violin model would be a Christmas gift I’d welcome. Anyone care to guess the date of this ad? I’m going to say late forties/early fifties…

Jack Benny's Making His ListSome of us are getting Christmas shopping underway this weekend, so it seemed as good a time as any to pass along one of Jack Benny’s ideas for gift giving. How could Jack have known back in the forties (?) how controversial that carton of Luckies would become in any number of households within a few decades? I just read about one town where they’ve outlawed smoking in homes. Wonder how Benny would have reacted to a headline like that! He’s certainly laid in a supply, and among the list of recipients, I do recognize George Burns, Gracie Allen, and --- is that Merle Oberon’s name? His neat little miniature violin model would be a Christmas gift I’d welcome. Anyone care to guess the date of this ad? I’m going to say late forties/early fifties…

Boris Karloff --- Part Two

Boris Karloff --- Part Two Slide whistles in the main title theme of a Boris Karloff vehicle would seem neither welcome nor appropriate, but that’s just the opening bell for 66 minutes of derivative slap-stick-ery inspired by the success of Broadway’s Arsenic and Old Lace. The Boogie Man Will Get You was in theatres by October 1942, long before Warners could release its screen adaptation of the Karloff stage smash, allowing this pallid facsimile to give provincial audiences a taste of what they’d been reading about in Life and The Saturday Evening Post. Arsenic was black comedy of a sort new to movies, and Boogie Man treaded a ridge between harmless plagiarism and outright, actionable theft. This time Karloff’s misunderstood scientist was played for laughs, only here the yoks are few, so often the case when we’re force-fed zany antics by players straining too hard for the effect. Bodies are piling up in Karloff’s basement, but I had a feeling none of them were really dead, for if they were, he’d soon enough be facing the same electric chair that claimed him in previous Columbia outings. Sure enough, the "corpses" march unceremoniously through his lab just before the fade, arriving as if on cue to checkmate possible Code intervention. Karloff had a deft hand for comedy, and his parlays with Peter Lorre anticipate future teamings on Route 66 and AIP’s The Comedy Of Terrors, itself a similarly labored exercise in dark humor. The great thing about Arsenic and Old Lace (pictured below is a still from the Broadway production) was the prestige it conferred upon Karloff at a time when his career really needed a jolt. A "B" level comedy/horror for Columbia was tangible expression of the actor’s new status, but the truer reward by far was conferred by Universal two years later when they combined Technicolor with a big-budget musical thriller starring Boris Karloff …

Slide whistles in the main title theme of a Boris Karloff vehicle would seem neither welcome nor appropriate, but that’s just the opening bell for 66 minutes of derivative slap-stick-ery inspired by the success of Broadway’s Arsenic and Old Lace. The Boogie Man Will Get You was in theatres by October 1942, long before Warners could release its screen adaptation of the Karloff stage smash, allowing this pallid facsimile to give provincial audiences a taste of what they’d been reading about in Life and The Saturday Evening Post. Arsenic was black comedy of a sort new to movies, and Boogie Man treaded a ridge between harmless plagiarism and outright, actionable theft. This time Karloff’s misunderstood scientist was played for laughs, only here the yoks are few, so often the case when we’re force-fed zany antics by players straining too hard for the effect. Bodies are piling up in Karloff’s basement, but I had a feeling none of them were really dead, for if they were, he’d soon enough be facing the same electric chair that claimed him in previous Columbia outings. Sure enough, the "corpses" march unceremoniously through his lab just before the fade, arriving as if on cue to checkmate possible Code intervention. Karloff had a deft hand for comedy, and his parlays with Peter Lorre anticipate future teamings on Route 66 and AIP’s The Comedy Of Terrors, itself a similarly labored exercise in dark humor. The great thing about Arsenic and Old Lace (pictured below is a still from the Broadway production) was the prestige it conferred upon Karloff at a time when his career really needed a jolt. A "B" level comedy/horror for Columbia was tangible expression of the actor’s new status, but the truer reward by far was conferred by Universal two years later when they combined Technicolor with a big-budget musical thriller starring Boris Karloff …

The Climax is Universal-ly reviled by fans of Karloff, but when was any horror headliner otherwise entrusted with Technicolor amidst "A" trappings? The previous year’s Phantom Of the Opera was thought too lofty for the likes of Chaney, Jr., despite his familial links with the role and contract availability. Were it not for Arsenic and Old Lace, I doubt very much if Karloff would have gotten The Climax, even if Universal did play games with his billing (first position in the credits, but second to Susanna Foster in the trailer). I like this show because Karloff is at all times elegant and commanding. He’s also striking in Technicolor, enjoying plush accommodations denied him at Columbia and in lesser Universals. Horror fandom seldom overlaps with an appreciation for Susanna Foster, so I can understand the antipathy viewers feel toward The Climax. Universal would easily score bookings for a lavish follow-up to Phantom Of The Opera in theatres that wouldn’t dream of playing The Boogie Man Will Get You. Cheap horror movies were not for first-run houses. The Climax was sold as something quite different (and that's actress June Vincent with Karloff during an on-set break). Universal’s trailer emphasizes Karloff’s Arsenic antecedents. Romantic lead Turhan Bey, himself a veteran of previous horrors, is now celebrated as a romantic new star, acclaimed for his role in "Dragon Seed." The idea was to disassociate these players from low-budget monster movies, as premiere audiences of the day had no more interest in these than modern day Karloff fans have for Susanna Foster or Turhan Bey. With its emphasis on music, The Climax can’t help but disappoint horror mavens, but is it really any worse than the 1943 Phantom Of the Opera in that respect?

I don’t like seeing Karloff belittled and pushed around, least of all by the cut-rate likes of Stephen McNally, whose sole worthwhile accomplishment at the time of The Black Castle had been stealing Jim Stewart’s rifle in Winchester ’73 and engaging in some reasonably colorful villainy therein. Why diminish Karloff in these fifties costumed gothics? Was he regarded as too old to carry the lead? I wanted to see him play McNally’s part in The Black Castle. Imagine Boris with a patch over his eye, consigning victims to those same alligator pits McNally presides over so listlessly. And what twisted form of logic confers top billing and the leading role to past-his-prime Richard Greene? Watching The Black Castle was a bitter experience for this Karloff admirer. I’d glimpse him briefly fifteen minutes in, then he’d disappear for several reels. The role could have been played by Paul Cavanagh, Alan Napier (and both do lend minor support in The Strange Door), or any number of competent thesps. It’s obvious they only hired Karloff for his name, much as was the case with Bela Lugosi and Night Monster. There’s more effort toward selling Richard Greene as a swashbuckling romantic, Flynn-ed out in sword fights and tavern brawls. The Black Castle is no more a horror film than The Prince Who Was A Thief, The Golden Blade, or a dozen other Universal-International pageants, and I could as easily imagine Jeff Chandler or Rock Hudson playing this at about the same level of competence as Greene. As for Karloff, he was actually better served as Dr. Jekyll and (being doubled as) Mr. Hyde opposite Abbott and Costello.

Karloff doesn’t enter The Strange Door. He’s dragged in, thrown on the floor, and kicked by a top-billed Charles Laughton. Much of the film is taken up with the frustrated romance of two utterly vapid young players, Richard Stapley (once a Hal Wallis contract hopeful) and Sally Forrest (whose own billing was increased to equal prominence with Laughton and Karloff in a special pressbook supplement). Those tavern dust-ups so beloved of unimaginative Universal writers are given play in the opening reel of The Strange Door, and despite atmospheric graveyards and castle sets to come, we know horror themes will run a distant second to generic action-adventure content. Everyone seems committed to withholding Karloff’s presence. His is the mysterious eye peeking through walls for most of these 81 minutes, an impassive and largely offscreen observer of Charles Laughton’s flamboyant over-playing. The Strange Door was a step down for Laughton as well, though his motives were pure in that he wanted to finance his ongoing acting workshops and used fees from films like this (and Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd) to do it. If uninhibited Laughton is your meat, here is a banquet of same. Would that Karloff have had such a rich histrionic opportunity! As it is, he’s the loyal, self-sacrificing family servant (always the weakest role in any cast), whose voluntary forfeitures on behalf of undeserving masters seem pointless and unmotivated. No man (or actor) at 64 should have to endure two gunshots, night swims across a moat (after being shot), and a literal backstabbing from one whose part he should have played. Karloff might have managed all this twenty years before, but seeing him attempt it now, in the service of such a poor vehicle, makes you wish he could have collected the fee for less strenuous work --- live television perhaps, or another of his radio quiz programs (above at a broadcast with western great William S. Hart and Rudy Vallee). Considering the sorry state of horror films in the early fifties (and their further erosion as sci-fi took over), we can be thankful Karloff had the refuge of stage work (plus radio and TV) to sustain him. The Universal DVD box includes The Strange Door, The Black Castle, The Climax, Tower Of London, and Night Key. These represent lows and a few highs in his career, but all are well worth seeing, as are the Columbias, and the prices for both sets are irresistible.

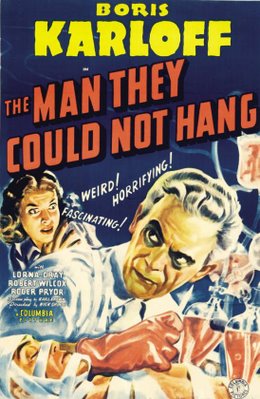

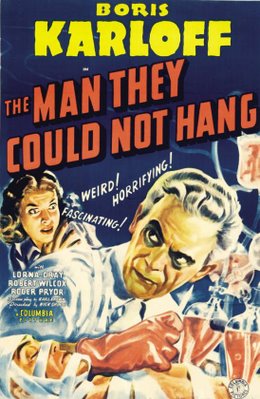

Karloff Columbia NumbersHere's a listing of domestic rentals for six films Boris Karloff did at Columbia. Considering the modest figures shown here, you can imagine why it was necessary to hold down the budgets for these shows. Karloff's vehicles were not unlike serials and "B" westerns in that respect ...The Black Room --- $187,000The Man They Could Not Hang --- $183,000The Man With Nine Lives --- $156,000Before I Hang --- $117,000The Devil Commands --- $120,000The Boogie Man Will Get You --- $160,000

119 Thanksgivings Ago, Boris Was Born! --- Part One

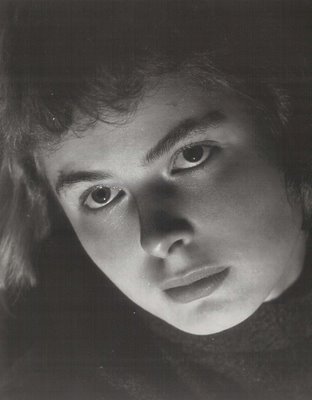

119 Thanksgivings Ago, Boris Was Born! --- Part One I don’t know if it’s by accident or design, but 2006 seems to have been the year of Boris Karloff on DVD. His name and image has been well marketed since 1993 when daughter Sarah took over licensing of same, and that’s been a good thing for the Karloff legacy, as he still commands enough fan following to be the star attraction in two box sets from major distributors. Pretty amazing for a man born 119 years ago today. Would kids notice Karloff on a Best Buy display rack? I’m in no position to say, being clearly prejudiced in favor of an icon I grew up with, but how much awareness do younger viewers have of these Universal horror films? Perhaps more than we think. Fans of middle-aged duration imagine them to have disappeared along with all those local Shock Theatres, but did they? The recent obituaries for VHS reminded me that home video’s been with us nearly thirty years, and the key Karloff titles have been available for most of these. Satellite television has delivered the Frankensteins and Mummys ongoing for nearly as long, but how wide an audience has AMC and TCM reached during these last decades? I keep wondering if there will be anyone behind my age group to carry the banner for these old horror films. Universal and Columbia must surely be counting on major boomer support for the Karloff obscurities they’ve recently released on DVD. Having plowed more fertile ground by repeated dips into the famous monsters of their respective filmlands, studios have exhumed all the Frankensteins, Draculas, and Invisible Men on hand. Now what’s left are runts from the litter we’ve awaited with even greater anticipation. Has anyone seen Night Key since the seventies? Not me. Columbias like Before I Hang and The Boogie Man Will Get You have gathered dust since the old Shock! package scattered in 1971. The only way you’d see these was on a collector’s 16mm screen or some bootlegged video off a monster-con dealer table. To have them so pristinely available is to realize a dream of years duration, for there’s no group of features so evocative of long ago late-nights as these.

I don’t know if it’s by accident or design, but 2006 seems to have been the year of Boris Karloff on DVD. His name and image has been well marketed since 1993 when daughter Sarah took over licensing of same, and that’s been a good thing for the Karloff legacy, as he still commands enough fan following to be the star attraction in two box sets from major distributors. Pretty amazing for a man born 119 years ago today. Would kids notice Karloff on a Best Buy display rack? I’m in no position to say, being clearly prejudiced in favor of an icon I grew up with, but how much awareness do younger viewers have of these Universal horror films? Perhaps more than we think. Fans of middle-aged duration imagine them to have disappeared along with all those local Shock Theatres, but did they? The recent obituaries for VHS reminded me that home video’s been with us nearly thirty years, and the key Karloff titles have been available for most of these. Satellite television has delivered the Frankensteins and Mummys ongoing for nearly as long, but how wide an audience has AMC and TCM reached during these last decades? I keep wondering if there will be anyone behind my age group to carry the banner for these old horror films. Universal and Columbia must surely be counting on major boomer support for the Karloff obscurities they’ve recently released on DVD. Having plowed more fertile ground by repeated dips into the famous monsters of their respective filmlands, studios have exhumed all the Frankensteins, Draculas, and Invisible Men on hand. Now what’s left are runts from the litter we’ve awaited with even greater anticipation. Has anyone seen Night Key since the seventies? Not me. Columbias like Before I Hang and The Boogie Man Will Get You have gathered dust since the old Shock! package scattered in 1971. The only way you’d see these was on a collector’s 16mm screen or some bootlegged video off a monster-con dealer table. To have them so pristinely available is to realize a dream of years duration, for there’s no group of features so evocative of long ago late-nights as these.

Again, it’s not a question of whether they’re "good" pictures. I’d surely court viewer rejection and my own hurt feelings, were I to show The Climax to an uninitiated audience, for they’d be right in questioning my programming judgment. Both sets are for Karloff fans who understand. To enjoy these is to make allowances for them. They’re the ones you watch alone. Night Key was where I decided to start. No apologies or explanations necessary, for I enjoyed it by myself, thus spared the natterings of those who would remind me that it isn’t even a horror movie. So what’s wrong with a "B" crime melodrama, as long as Karloff’s in the lead? Doesn’t Night Key’s charter membership in the original Shock! group entitle it to respect? Never mind the misleading poster art shown here. It would suggest a vigorous Karloff up to old horrific tricks, not the frail inventor he actually portrays in the film, altogether immobilized by the mere removal of his eyeglasses. Topic A in this show is burglar alarms, so only hardcore Boris boosters need apply. I enjoyed Night Key because I’m happy to pan for gold in these sets. The visual splendor of this hitherto grayish and washed-out 1937 feature was enough to bear me upon wings of rapture throughout, as it never looked so good before. Columbia’s stoutest DVD offering is The Black Room. It’s a stand-alone gothic novelty as opposed to later off-the-rack thrillers. Karloff plays good/evil twin brothers and would show anyone here what a great actor he could be. This is where you'll quell scoffers and perhaps convert non-believers. I promise they’ll dig the scene where Boris has to sign a paper with his right hand (don’t ask, just watch it). You won’t have to set up your crowd for The Black Room. It’s plain satisfying (as well as satisfyingly brief) and itself worth the price of the set.

My aggravation with the Columbia science group lies in the fact that Boris Karloff’s laboratory findings are so sound, so obviously right, that to march him gallows-bound for advancing them seems churlish and altogether unreasonable. He’s constantly beset with small-minded functionaries determined to enforce the law, even when that means switching off his artificial heart moments prior to its revolutionizing medicine. Karloff’s informed arguments are never persuasive with these troglodytes. We’re always with him when he consequently seeks vengeance from beyond the grave. Last-reel endorsements of the status quo are insults not only to Karloff, but to our patience and intelligence as well. I wanted to see him pick off all those jurors one by one in The Man They Could Not Hang, and felt cheated when plot contrivances intervened. The science-gone-wrong quartet for Columbia was four strips from a single bolt of cloth. How maddening to see so many worthwhile experiments so utterly thwarted. As a child, I used to wish they’d just once let the poor man finish what he was doing. Maybe this was Karloff’s magic for boys growing up. Forever was he slapped down and persecuted despite reasoned explanations and pure motives, precisely those qualities brought to bear by ten-year olds during attempts to reason with misguided parents. Horror movie conventions decreed Karloff commit at least one murder, with a vigilant Production Code close behind to require the supreme penalty, always a harsh and punitive one to my mind. Be prepared to soothe the vexation of such injustice with perhaps a favored candied treat, or even stronger libation if indeed that’s what it takes to relieve your frustrated empathy on Karloff’s behalf.

My aggravation with the Columbia science group lies in the fact that Boris Karloff’s laboratory findings are so sound, so obviously right, that to march him gallows-bound for advancing them seems churlish and altogether unreasonable. He’s constantly beset with small-minded functionaries determined to enforce the law, even when that means switching off his artificial heart moments prior to its revolutionizing medicine. Karloff’s informed arguments are never persuasive with these troglodytes. We’re always with him when he consequently seeks vengeance from beyond the grave. Last-reel endorsements of the status quo are insults not only to Karloff, but to our patience and intelligence as well. I wanted to see him pick off all those jurors one by one in The Man They Could Not Hang, and felt cheated when plot contrivances intervened. The science-gone-wrong quartet for Columbia was four strips from a single bolt of cloth. How maddening to see so many worthwhile experiments so utterly thwarted. As a child, I used to wish they’d just once let the poor man finish what he was doing. Maybe this was Karloff’s magic for boys growing up. Forever was he slapped down and persecuted despite reasoned explanations and pure motives, precisely those qualities brought to bear by ten-year olds during attempts to reason with misguided parents. Horror movie conventions decreed Karloff commit at least one murder, with a vigilant Production Code close behind to require the supreme penalty, always a harsh and punitive one to my mind. Be prepared to soothe the vexation of such injustice with perhaps a favored candied treat, or even stronger libation if indeed that’s what it takes to relieve your frustrated empathy on Karloff’s behalf.

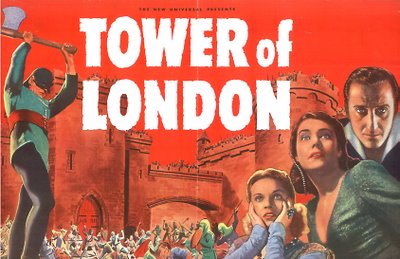

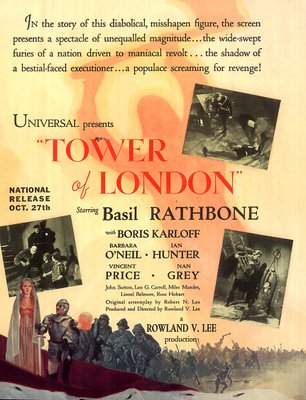

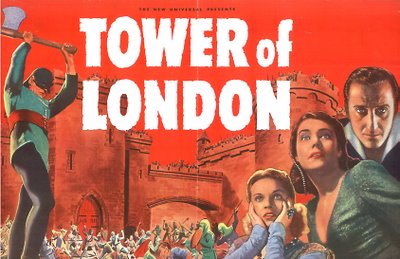

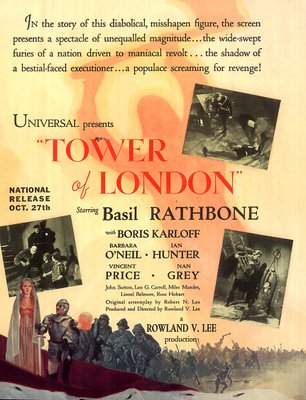

Our birthday man takes greater command in Tower Of London, wherein he’s the one doling out executions and lobbing off innocent heads. Universal’s (though not necessarily other’s) idea of an "A" picture in 1939, this was really Basil Rathbone’s showcase, and though Boris walks tall (even with a clubfoot), he’s still playing in support to the bigger name. Tower Of London was never easy to see, as it wasn’t included in the initial Shock! packages, and tended to crop up (if rarely) among mainstream titles on programming schedules. Universal used shows like this to capture an audience beyond the horror niche. It could as easily be sold as historical drama, with even a nod toward Shakespeare’s Richard III. Cast members Basil Rathbone and Vincent Price were not then linked with horror films, and even Karloff’s association with the genre was deluded somewhat by his ongoing participation in tepid mysteries of a Mr. Wong sort. The double shot of Tower Of London and the preceding Son Of Frankenstein was his triumphant return to sinister parts, where Karloff’s own physical characteristics could again serve the characters he was playing. Mord The Executioner drags an arresting clubfoot in Tower Of London, but it’s those naturally bowed legs of Karloff’s that make it so effective. Chaney Senior could not have devised such a striking visual as Karloff manages here. His frightful countenance is further enhanced by tights he wears throughout, surely a first for this actor. Torture scenes are frequent and delightful, with Karloff gleefully presiding over varied sessions with assorted devices. I wondered if the Code police weren’t sleeping during much of this, but at least Boris fans were getting what they came for after what must have seemed a long drought. Tower Of London was the happy return of a physically active Karloff, as even his Frankenstein monster seemed excessively sedentary in the third round of that series he’d recently completed, and indeed, Tower's probably the best feature in Universal’s DVD box of five.

One Last Footnote On BergmanAt the risk of belaboring the subject of Ingrid Bergman, here is an image I came across that just has to be shared. It was taken in 1949, and purports to show Roberto Rossellini and the actress leaving Stromboli to ask Bergman’s husband for a divorce. Their troubled expressions would suggest it’s a true enough caption, and the weather that day can only have increased their misery. In light of the scandal swirling around them, I doubt this was anything other than an accurate rendering of what these two were going through. Put this under the heading of Photos Don't Lie.

One Last Footnote On BergmanAt the risk of belaboring the subject of Ingrid Bergman, here is an image I came across that just has to be shared. It was taken in 1949, and purports to show Roberto Rossellini and the actress leaving Stromboli to ask Bergman’s husband for a divorce. Their troubled expressions would suggest it’s a true enough caption, and the weather that day can only have increased their misery. In light of the scandal swirling around them, I doubt this was anything other than an accurate rendering of what these two were going through. Put this under the heading of Photos Don't Lie.

On another topic, I note that several sites are taking a holiday break. For what it’s worth, Greenbriar will be open as usual tomorrow, as there is a very special birthday that’s shared with Thanksgiving this year, and we want to be here to celebrate (can anybody guess whose it is?).

Ingrid Bergman --- Part Two

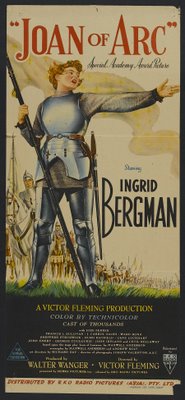

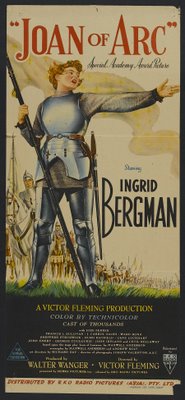

Ingrid Bergman --- Part Two The jinx may well have set in before the Italian debacle(s). The charmed professional life of Spellbound, The Bells Of St. Mary’s, and Notorious placed Bergman on better marquees throughout the nation. We may not revere Saratoga Trunk, but it’s down on Warner books as one of their all-time profit pictures from that era (3.4 million), and indeed, 1946 seemed a year in which an Ingrid Bergman show was playing around every street corner. So where do you go from the top except down? The Four Horsemen of Ingrid’s Apocalypse would ride in grim succession. Arch Of Triumph was 131 minutes of galloping pretension. Joan Of Arc was the role she’d obsessed on since making landfall in the US. Her Broadway triumph as Joan Of Lorraine suggested a warm reception for a movie adaptation, but cost overruns on the independent production (in which she was a participant) made Gone With The Wind look like something out of Monogram. Were it not for the 4.5 million spent, Joan Of Arc might have had a major pay-off, for crowds responded to the tune of six million in worldwide rentals, but reviews were spotty and viewers were bored. Bergman had been intimate with director Victor Fleming (he of a previous assignation with Clara Bow), but the veteran director dropped dead shortly after Joan was completed, some guessing he’d succumbed from the stress of it all. Under Capricorn was Hitchcock being experimental --- this was his run at independence after suffocating years with Selznick. He and Bergman were alike for having plowed fields for a producer who then harvested the bounty, but neither were equipped to administer production on their own, where one disaster could ring down the curtain on a whole company. Hitchcock had his with Under Capricorn, while Bergman finished her quartet of losers with Stromboli, a would-be art movie born with a gushing fan letter to its director, Roberto Rossellini, and ending with Ingrid’s career in ruins.

The jinx may well have set in before the Italian debacle(s). The charmed professional life of Spellbound, The Bells Of St. Mary’s, and Notorious placed Bergman on better marquees throughout the nation. We may not revere Saratoga Trunk, but it’s down on Warner books as one of their all-time profit pictures from that era (3.4 million), and indeed, 1946 seemed a year in which an Ingrid Bergman show was playing around every street corner. So where do you go from the top except down? The Four Horsemen of Ingrid’s Apocalypse would ride in grim succession. Arch Of Triumph was 131 minutes of galloping pretension. Joan Of Arc was the role she’d obsessed on since making landfall in the US. Her Broadway triumph as Joan Of Lorraine suggested a warm reception for a movie adaptation, but cost overruns on the independent production (in which she was a participant) made Gone With The Wind look like something out of Monogram. Were it not for the 4.5 million spent, Joan Of Arc might have had a major pay-off, for crowds responded to the tune of six million in worldwide rentals, but reviews were spotty and viewers were bored. Bergman had been intimate with director Victor Fleming (he of a previous assignation with Clara Bow), but the veteran director dropped dead shortly after Joan was completed, some guessing he’d succumbed from the stress of it all. Under Capricorn was Hitchcock being experimental --- this was his run at independence after suffocating years with Selznick. He and Bergman were alike for having plowed fields for a producer who then harvested the bounty, but neither were equipped to administer production on their own, where one disaster could ring down the curtain on a whole company. Hitchcock had his with Under Capricorn, while Bergman finished her quartet of losers with Stromboli, a would-be art movie born with a gushing fan letter to its director, Roberto Rossellini, and ending with Ingrid’s career in ruins.

Post-war European filmmakers had to shoot in the streets for lack of indoor facilities, their stages having been blown asunder during the conflict. (Extreme) austerity makes naturalists of us all, and directors like Rossellini had little choice but to take to the sidewalks with non-professional casts and shoot whatever took place there. Pampered Hollywood was stunned by the harsh realism, and audiences responded to gritty, gloves-off pictures like Open City and The Bicycle Thief. Roberto Rossellini was the (apparent) autuer behind the former, and when Ingrid Bergman caught Open City in a New York art-house, she swore to one day work with the genius behind it. The Italian director had already negotiated with Selznick, who was himself impressed with neo-realists, and would indeed support future projects involving Euro talent, but Rossellini was too capricious and disorganized for even this producer’s taste, and their talks soon broke down. Bergman’s aforementioned letter was simple and direct. She’d come to Italy and work for Rossellini if he’d have her. This was opportunity banging loudly at his door, and Roberto was quick as a flash to arrange a meeting. Clueless Petter Lindstrom bade enter to the director, who then conducted a campaign of professional (and personal) seduction while a guest in the man’s home. By the time Rossellini left, he had Bergman in his pocket. Stromboli would be their first collaboration. There was no script. The cast was filled with interesting faces so beloved of the director, but none of them were actors. Its volcano location was nearly inaccessible, and an indecisive Rossellini frittered away weeks dreaming up something for the cast to do. Turns out capable assistants (including Frederico Fellini) were largely responsible for the stories that had made Rossellini’s previous pictures work. Without them, he was floundering. Bergman was beginning to realize this was an emperor without clothes, but he’d deftly talked the actress out of hers, with the result being a pregnancy out of wedlock (with him anyway) and a ravenous press poised for a slow kill.

Post-war European filmmakers had to shoot in the streets for lack of indoor facilities, their stages having been blown asunder during the conflict. (Extreme) austerity makes naturalists of us all, and directors like Rossellini had little choice but to take to the sidewalks with non-professional casts and shoot whatever took place there. Pampered Hollywood was stunned by the harsh realism, and audiences responded to gritty, gloves-off pictures like Open City and The Bicycle Thief. Roberto Rossellini was the (apparent) autuer behind the former, and when Ingrid Bergman caught Open City in a New York art-house, she swore to one day work with the genius behind it. The Italian director had already negotiated with Selznick, who was himself impressed with neo-realists, and would indeed support future projects involving Euro talent, but Rossellini was too capricious and disorganized for even this producer’s taste, and their talks soon broke down. Bergman’s aforementioned letter was simple and direct. She’d come to Italy and work for Rossellini if he’d have her. This was opportunity banging loudly at his door, and Roberto was quick as a flash to arrange a meeting. Clueless Petter Lindstrom bade enter to the director, who then conducted a campaign of professional (and personal) seduction while a guest in the man’s home. By the time Rossellini left, he had Bergman in his pocket. Stromboli would be their first collaboration. There was no script. The cast was filled with interesting faces so beloved of the director, but none of them were actors. Its volcano location was nearly inaccessible, and an indecisive Rossellini frittered away weeks dreaming up something for the cast to do. Turns out capable assistants (including Frederico Fellini) were largely responsible for the stories that had made Rossellini’s previous pictures work. Without them, he was floundering. Bergman was beginning to realize this was an emperor without clothes, but he’d deftly talked the actress out of hers, with the result being a pregnancy out of wedlock (with him anyway) and a ravenous press poised for a slow kill.

Worse luck, her business manager had been systematically robbing Ingrid back in the states, and by the time anyone caught on, he’d taken the gas-pipe and left her stony. Husband Lindstrom set upon a vindictive course, and turned their daughter against her. Joan Of Arc was suddenly a devil incarnate, and broke besides. US exhibitors cancelled Stromboli bookings after her child was born in Italy. Rossellini married her in the wake of the divorce, but made it known she’d not work for directors other than himself. Senate members suggested her visa be picked up, a matter of little consequence in light of press so foul she’d not enter the US in any case. Bergman was restricted, if not condemned, to Rossellini films from here on, each one a step down from the previous. The visionary of Open City was spending money and racing about in Ferraris while debts piled up. What movie deals he got were owed to his wife’s diminished prestige, and what grosses they earned were restricted to the continent, as Bergman were strictly poison in the US (a 1954 re-issue of Saratoga Trunk took just $110,000 in domestic rentals). She’d be thoroughly deglamorized in bleak Rossellini projects he imposed upon her, not so bad an idea in itself were he not so intent upon it. Europa ’51 went nowhere in Europe or the Americas, and Viaggio in Italia was a more-or-less ad-libbed domestic drama with George Sanders, who was unflappable in most circumstances, but Rossellini’s lack of preparedness gave even Sanders a nervous breakdown. The latter was shot in English language, so it’s at least marginally more accessible than the others, and Martin Scorsese has been an eloquent champion of these films in his documentary, My Voyage To Italy, so there are clearly values here worth exploring. Too bad no such defenders arose when they were new, for the unhappy end result was a near-total creative collapse for Rossellini and years of career stagnation for his wife.

Worse luck, her business manager had been systematically robbing Ingrid back in the states, and by the time anyone caught on, he’d taken the gas-pipe and left her stony. Husband Lindstrom set upon a vindictive course, and turned their daughter against her. Joan Of Arc was suddenly a devil incarnate, and broke besides. US exhibitors cancelled Stromboli bookings after her child was born in Italy. Rossellini married her in the wake of the divorce, but made it known she’d not work for directors other than himself. Senate members suggested her visa be picked up, a matter of little consequence in light of press so foul she’d not enter the US in any case. Bergman was restricted, if not condemned, to Rossellini films from here on, each one a step down from the previous. The visionary of Open City was spending money and racing about in Ferraris while debts piled up. What movie deals he got were owed to his wife’s diminished prestige, and what grosses they earned were restricted to the continent, as Bergman were strictly poison in the US (a 1954 re-issue of Saratoga Trunk took just $110,000 in domestic rentals). She’d be thoroughly deglamorized in bleak Rossellini projects he imposed upon her, not so bad an idea in itself were he not so intent upon it. Europa ’51 went nowhere in Europe or the Americas, and Viaggio in Italia was a more-or-less ad-libbed domestic drama with George Sanders, who was unflappable in most circumstances, but Rossellini’s lack of preparedness gave even Sanders a nervous breakdown. The latter was shot in English language, so it’s at least marginally more accessible than the others, and Martin Scorsese has been an eloquent champion of these films in his documentary, My Voyage To Italy, so there are clearly values here worth exploring. Too bad no such defenders arose when they were new, for the unhappy end result was a near-total creative collapse for Rossellini and years of career stagnation for his wife.

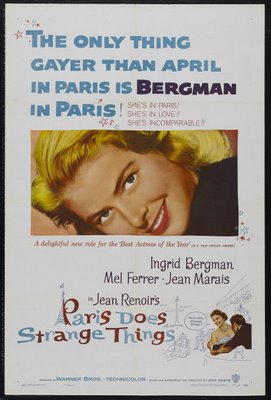

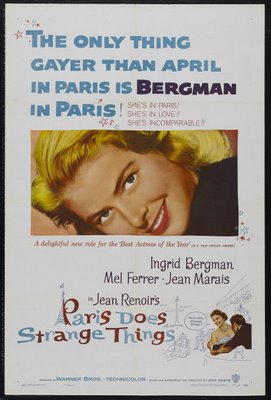

There had been feelers from Hollywood. George Cukor wanted her for a project, and others were anxious to assist in a comeback, but Rossellini nixed all such overtures. An actress with her gifts would only remain caged so long, however, and by 1956, she was ready to break out. Tea and Sympathy would be a stage comeback, followed by collaboration with noted director Jean Renoir, whose Elena and Her Men was perhaps too French for domestic palettes, but did at least suggest there was a star waiting to be reborn. It was released stateside as Paris Does Strange Things, but Warners collected a peaked $185,000 in domestic rentals, scarcely enough to justify the import. The original French-language version remained largely unseen until Kino released a stunning DVD last year, which showed this beautiful color production off to its best advantage. The real breakthrough was Anastasia, and that resulted in an Academy Award, so obviously all was forgiven. Indiscreet reunited Bergman with Cary Grant, who’d stuck by her through the bad patch, but time and stress had aged her beyond those parts that brought glory a decade before, and a new generation of leading ladies had emerged besides. She was a prestigious name for infrequent television appearances, but none of these features could put her back in a winner’s circle --- Goodbye, Again, The Visit, The Yellow Rolls-Royce --- too much momentum lost, and now she was firmly identified with old Hollywood. There was a comeback in the form of another Academy Award for a character role in Murder On The Orient Express, and distinquished work along these lines continued through the seventies. Memoirs were inevitable, and hers were more dignified than most, but in how many interviews can one explain what it was like working with Humphrey Bogart? She made a final TV-movie while gravely ill, having never lost the indomitable will to stay in harness. She died on her sixty-seventh birthday in 1982.

There had been feelers from Hollywood. George Cukor wanted her for a project, and others were anxious to assist in a comeback, but Rossellini nixed all such overtures. An actress with her gifts would only remain caged so long, however, and by 1956, she was ready to break out. Tea and Sympathy would be a stage comeback, followed by collaboration with noted director Jean Renoir, whose Elena and Her Men was perhaps too French for domestic palettes, but did at least suggest there was a star waiting to be reborn. It was released stateside as Paris Does Strange Things, but Warners collected a peaked $185,000 in domestic rentals, scarcely enough to justify the import. The original French-language version remained largely unseen until Kino released a stunning DVD last year, which showed this beautiful color production off to its best advantage. The real breakthrough was Anastasia, and that resulted in an Academy Award, so obviously all was forgiven. Indiscreet reunited Bergman with Cary Grant, who’d stuck by her through the bad patch, but time and stress had aged her beyond those parts that brought glory a decade before, and a new generation of leading ladies had emerged besides. She was a prestigious name for infrequent television appearances, but none of these features could put her back in a winner’s circle --- Goodbye, Again, The Visit, The Yellow Rolls-Royce --- too much momentum lost, and now she was firmly identified with old Hollywood. There was a comeback in the form of another Academy Award for a character role in Murder On The Orient Express, and distinquished work along these lines continued through the seventies. Memoirs were inevitable, and hers were more dignified than most, but in how many interviews can one explain what it was like working with Humphrey Bogart? She made a final TV-movie while gravely ill, having never lost the indomitable will to stay in harness. She died on her sixty-seventh birthday in 1982.

Photo CaptionsColor Publicity for SelznickIngrid Bergman as Broadway's Joan Of Lorraine With Cary Grant in NotoriousHolding a pivotal key in NotoriousFan Magazine Color PortraitAustralian Poster for Joan Of ArcWith Joseph Cotten in Under CapricornAnother Color Fan Mag PortraitStromboliWith Yul Brynner and Helen Hayes in AnastasiaOne-Sheet for Paris Does Strange Things