The Greatest Story Ever Told --- Part Two

George Stevens had no doubts that The Greatest Story Ever Told would be made. The only certainty as of September 1961 was that 20th Century Fox wouldn’t be making it. Fine, he said. Three other American companies and two European financing groups stood ready, and one of these represented a better deal than Fox had given him. Whatever delays were attendant upon 20th’s withdrawal, Greatest Story would go before cameras early in 1962, he promised. In the meantime, Stevens and staff continued screening all of Hollywood’s past biblical output to make sure theirs avoided pitfalls of general superficiality and … assembly-line approach. Bible movies, said Stevens, are the only sort of films still in their infancy. Financial rescue came in November 1961. United Artists stepped up with, among other things, absolute freedom on artistic matters for the producer-director, along with unlimited completion responsibility. That last part would help send costs skyward. According to Tino Balio’s excellent book, United Artists: The Company That Changed The Film Industry, UA had no overbudget protection with Stevens. He’d give up none of his agreed-upon 75% of profits, whatever the cost overruns incurred (GS also collected a $300,000 producer’s fee). UA would fall into what Balio called a blockbuster trap exacerbated by production delays, foul weather, and logistics of shooting on location with an enormous cast and crew. Stevens wanted to film in the US, having toured Holyland sites and deeming them wholly unsatisfactory (though publicity for having walked paths Christ trod was invaluable). Parts of Utah and Arizona would plausibly stand in. The director had never shot a feature offshore and didn’t propose doing so now.

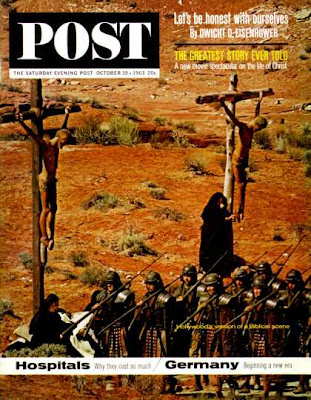

The Greatest Story Ever Told became a production saga with no apparent end in sight. The intimate drama of Christ and his teachings that Stevens envisioned was spread to Cinerama proportions in accord with United Artists’ pact to utilize the process on a slate of big releases to come. "Secret tests" were conducted in August 1962 to determine viability of filming Cinerama with a single camera rather than three as before. Stevens attended these demonstrations and brought along make-up and wardrobe tests he’d made for The Greatest Story Ever Told. He was unimpressed with the projected image and agreed that work lay ahead to perfect a revised Cinerama. Further research over the next six months produced what would become known as Ultra Panavision, a 70mm process that yielded an aspect ratio similar to three-strip Cinerama, but not as all-engulfing. Thanks to special rectified lens, you could project Ultra Panavision on a deeply curved screen, and there were no visible joins in the picture as had bedeviled previous Cinerama subjects. Stevens liked what he saw of this and incorporated it into Greatest Story shooting which began finally in autumn of 1962 and lasted nine months. The burden became such that two of Stevens’ director colleagues joined in to helm second units. David Lean oversaw Claude Rains’ scenes as King Herod and Jean Negulesco helped out in multiple capacities, all toward harnessing a ballooned enterprise whose budget had been revised (in summer 1963) to $12 million. Press visits to the set and locations assumed postures of hushed reverence. Ordinary conversation seemed to make spectators feel self-conscious, said one observer. Both LIFE and The Saturday Evening Post featured TGSET in multiple-page color spreads, with LIFE’s May 1964 coverage referring to $16 million poured into its telling. Said profligate spending became a focal point of interest. All of 1964 found Stevens buried in editing chambers with his masterpiece. Would this Greatest Story ever see the light of projection screens?

UA vice-president Robert Blumofe spoke to the company’s confidence in October 1964. "The Greatest Story Ever Told" might never be shown except in the Cinerama process, he claimed, United Artists has no plans for multiple runs after the film’s roadshow career and no 35mm prints will be made up. Blumofe refused to even estimate the film’s extraordinary earnings potential (that’s him at center above with Stevens to his left and Cinerama president William Forman at right). Director Stevens emphasized that his Greatest Story was made and designed to take advantage of the great Cinerama screen. Everyone counted on it to take permanent residence there. There was talk of opening TGSET for Christmas 1964, but insiders suggested Stevens was not happy about sharing the limelight with "My Fair Lady" or sharing possible Academy Awards. Warners’ musical premiered in October 1964, the same month word went out that Greatest Story had exceeded $20 million in costs. All Stevens needed was his film joining Cleopatra on extravagance scoreboards. A February 15, 1965 opening was set for New York and Los Angeles. Always the perfectionist when it came to exhibiting his films, Stevens did an inspection tour of theatres scheduled to run The Greatest Story Ever Told. What he saw at these roadshowing venues was not encouraging. People are paying higher prices for goldbricks, he said. The adult moviegoer was gradually being alienated as result of offenses committed by theatre managers and projectionists (a recent UCLA survey had indicated that average age of the latter was 67). Stevens’ idea was for distributors to band together and form a joint staff whose job it would be to visit theatres around the country and see that films are properly exhibited. To that end, he planned to put a crew in each house running The Greatest Story Ever Told to make sure presentations weren’t bungled. As these added up to sixty-three roadshow engagements, his task was both formidable and expensive.

Some reviews were good, but negative ones were noticed more. Maybe because these were so excoriating. Publicity’s overkill surely entered into critic’s glee in panning the Great Man’s sermon. Stevens had preached right to opening bell as to his movie's capacity to fill in the empty places and smooth over what is painful in patron’s lives. I think film has a unique way of expanding not only the comprehension of the viewer, but providing aspiration for a better life, a finer life. The director was clearly setting himself up for deflation, and you wish in hindsight he'd have stood back from quotes like these and realized he was perhaps a little too close to the majesty of his subject. Critical attacks cut deeply, of course. Worse than negative, they were mocking. The last thing Stevens expected was for people to ridicule his supreme effort. United Artists suggested one problem that could be fixed, and they were insistent as to that. Four hours!, screamed naysayers, as if that were Stevens’ towering offense. Well then, some of that would have to go, said UA. Music arranger and adapter Ken Darby worked with composer Alfred Newman on the film and wrote a book, Hollywood Holyland: The Filming and Scoring of The Greatest Story Ever Told, which tells of how Stevens spent days trimming reel-by-reel, pausing occasionally to consult review clippings he brought along for guidance. According to Darby, United Artists ordered an hour off the running time, but Stevens was able to hold the line at a little under half that. Anecdotal accounts of the premiere version as it differed from the subsequent one indicate that both the Crucifixion and the raising of Lazarus were shortened, along with numerous trims made from beginnings and ends of scenes throughout (all of which, said Darby, wreaked havoc on Newman’s music). Roadshows subsequent to New York and Los Angeles openers would run 199 minutes, including overture, intermission, and exit music, this reduced from Stevens’ intended 225 minute version. An even longer TGSET at 260 minutes has been alleged in years since, but not confirmed.

The film that would live fifty years was a commercial fiasco. United Artists took a drubbing like none they’d experienced before. The sixty-three roadshow sites reported back a combined gross of $8.977,892, from which UA saw rentals of $3.141,616. Whatever chance this film had of recovering its costs would have to be realized in a general release, an avenue the distributor had hoped to avoid. That would come in 1967, at which point The Greatest Story Ever Told was further cut, this time to 141 minutes. I recall it turning up that year in Kings Mountain, NC, a small town where we’d gone to visit my Grandmother. All set to leave for home that Sunday morning, I discovered that TGSET was playing at the local Joy Theatre. Could we maybe stick around for another day for me to catch it? I argued to my mother that it would be just like attending Sunday school, only for an entire afternoon, reasoning which got me nowhere. After that, sightings of The Greatest Story Ever Told were sporadic and sometimes bizarre. There was a 1972 reissue inspired by the Hippie Jesus fad, an ad for which is shown here (and thanks to Robert Cline for supplying it). I don’t know if this was a national or a regional campaign, but it was sure an unusual one. United Artists cushioned some losses by leasing Greatest Story to NBC for $5 million. That network premiered the film in two parts on Friday, April 12, 1974, with the conclusion broadcast the following night. Wanting to expand their showing to Easter event level, NBC opted for the second roadshow length, which, minus overture, intermission, and exit music, came to apx. 193 minutes. There were NBC repeats of the two-parts in 1975 and 1976, both for the Easter season. Pay-cable service Home Box Office ran The Greatest Story Ever Told in December 1980 just prior to its transfer to syndication as part of United Artists’ Showcase 11 package, which included 30 off-network features. TGSET was listed here as having a running time of 196 minutes. UA/16’s non-theatrical catalogue offered 16mm prints for rental in anamorphic format for $100, but only of the 141 minute version. What I saw on MGM-HD was 199 minutes, which included the overture/intermission/exit music. MGM’s DVD is also this longer cut. As to the fate of Stevens’ initial 225-minute version, there is a print reputedly stored at the Library Of Congress. Assuming it’s there, would anyone step up to rescue and restore The Greatest Story Ever Told?