Metro's Red Badge Blow-Off

How radical was John Huston’s The Red Badge Of Courage? Those insiders who saw his proposed version were impressed to a man. It was only when yahoos at the previews laughed and walked out that panic ensued. The story reads like a second act for The Magnificent Ambersons, another legendarily mutilated classic still unaccounted for in its entirety. Red Badge should have moved through the Metro system like dozens more literary adaptations going back to the company’s inception, so I’ve got to figure Huston’s treatment was at the least a major departure from formula they’d applied to those. Accounts of production and infighting abound thanks to a remarkable series of articles published in The New Yorker after Red Badge itself was dead and buried. Little time was needed for this one to evaporate out of theatres. Huston would remember it as his first film to lose money, and indeed it did ($940,000), though a lot of other MGM releases shed skin as well during those troubled years when a public seemed to have decided en masse to stop attending movies. For whatever good or bad reason, the studio gave writer Lillian Ross total access to staff involved with Red Badge and received for their hospitality a primer book (the collected articles appeared hardbound in 1952) on corporate myopia and venality. Huston sort of got out unscathed for having charmed the author, but others, including VP in charge of production Dore Schary (below with MGM's Leo the Lion), came off looking like a vacillating fathead bent on vandalizing a talented director’s work. Ross was probably right on that account. The Red Badge Of Courage looks to me to have been another of those pictures too far ahead of 1951 to survive that year intact. Everyone seemed desperate to salvage jobs placed in perceived jeopardy for having worked on it. They all nodded yes to scissors Schary personally applied after those disastrous previews and Huston splitting town to do The African Queen. Like Ambersons, it’s still a terrific show, but you have to decode much of Red Badge’s remains to divine what Huston had in mind. The real story was the off-set smack-down between Schary and soon-to-be-deposed Louis Mayer, who unwisely brandished this modest project (final negative cost: $1.642 million) as Exhibit A for a him-or-me ultimatum to New York studio chief (and deciding voter) Nicholas Schenck. Schary won, but blinked when the Red Badge pet he’d adopted grew teeth at those previews and threatened to become an audience joke received at his expense. To avert that, he’d simply cut it until the laughter stopped.

Red Badge seemed too inconsequential to arouse such backlot rancor, for Huston was at no time extravagant and his budget was actually exceeded by post-tinkering done by others. This was no Von Stroheim challenging studio authority. He’d just made money for them doing The Asphalt Jungle and was shaping up as one of postwar’s first total filmmakers worthy of rank alongside experienced writer-directors prized for being so few in number. His wild man ways were indulged for having delivered goods and showing a keen eye for what sold in theatres. According to some accounts, Huston turned in Red Badge Of Courage at less than ninety minutes (It was never a long picture, he later said). I’ve read variously of running times at 95 and 105 minutes. Some remembered two and a quarter hours of agony during test screenings wherein half the audience jeered and others walked out. Battle scenes were alleged to have been gorier and in greater abundance. Huston’s Civil War was far more hellish than conservative Metro was willing to depict. Mayer blanched at carnage and ruefully commented that it was typical of excess from this director (LB had heartily disapproved of The Asphalt Jungle as well). Other Metro personnel who’d liked Red Badge before chickened out now. Schary went to plucking and yes-men called him a hero for the result lasting just over an hour. The Motion Picture Herald announced release for September 1951 in July of that year, with running time to be 81 minutes, though by the August 18 trade screenings for exhibitors, it was down to a final 69 minutes. Everyone connected with the sorry affair spent remaining years trying to justify actions taken in mutual panic. Longtime MGM editor Margaret Booth told Focus On Film in 1976 that Red Badge was very long at first, that it was better shorter, and still managed somehow to emerge a classic. For his part, Huston seems not to have held grudges. He’d even hire Booth to edit his much later Fat City. Narration from Stephen Crane’s source book was appended to a reshuffled Red Badge to give literary weight and essentially dare patrons to ridicule it as they previously had.

It was clear those 69 minutes had been arrived at by way of hacking. Reviews were laudatory, but critics didn’t cover house nuts ruptured by a black-and-white downer about cowardice on the battlefield. Independent film buyers charting for The Motion Picture Herald called it poor. MGM’s New York sales division, where studio releases were made or broken, admitted indifference to investigating Lillian Ross, saying they’d known all along it would be a dog. Such candor as shared with an outsider was unprecedented. Red Badge ended up an art film (mis) handled by a company unequipped and frankly resentful of that label. Metro’s market was still a mass audience seated in big auditoriums, but here was a show that would reach neither. The fallback was to open (late by a month) at New York’s Trans-Lux 52nd Street art house, which seated 539 and was home to a number of Metro orphans thought unfit for wider bows (their Red Badge ad shown here). Opening a new picture at the Trans-Lux houses instead of on Broadway saves the major companies money for an elaborate house front, said the Herald. The New York newspapers devote an equal amount of space to reviews of pictures at the art houses. Thus the art spots, which formerly played British, Italian, or French product exclusively, are now getting the offbeat pictures from the majors --- and giving them long runs, which gives favorable word-of-mouth a chance to build business. The Trans-Lux was good for a six-to-eight week engagement of Metro peculiars like Teresa, Kind Lady, and The Man With A Cloak, far more than they would have played at a large Broadway house, said Boxoffice. Red Badge was offered up as another Gone With The Wind in print, while its trailer promised a latter-day Birth Of A Nation. Historians would damn Metro for playing it on double features, not realizing this was standard policy for all but potential biggies the company handled. Wider release did find Red Badge occupying lower berths, but so did most other black-and-white Metros done at reduced budget, and Schary’s mutilation was no diamond in the rough. There was little chance of Red Badge breaking out to attain sleeper status. Not with audiences rejecting it wholesale as they continued to do.

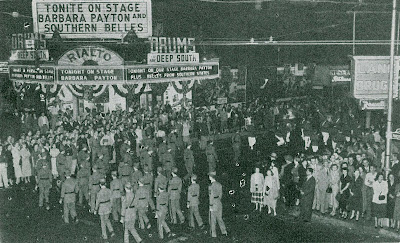

Variety spoke for a doubtful trade press as Red Badge went into general release, calling it curiously moody. Big returns do not appear likely, they added. Boxoffice appeal in the general market is rather limited, and in this release film will be best held to companion bookings. MGM’s misgivings having been confirmed, they now sent out The Red Badge Of Courage in support of features likely to perform better. In Boston, it buttressed Texas Carnival, a program held over in mid-October thanks to interest in the Esther Williams starrer (the latter's eventual profit was $709,000). Red Badge was second fiddle to The Strip in Denver, and Detroit saw it first-running beneath Across the Wide Missouri. The Red Badge Of Courage had legs weak as Metro’s other punk release that month, The Man With A Cloak, which was yanked off a single berth in Cincinnati after four days and replaced with oldie combo Luxury Liner and The Barkleys Of Broadway. Bitter experience taught MGM’s sales force not to persist once hothouse plants were identified as such. Best to let them play off and disappear. Final domestic rentals for Red Badge amounted to $789,000, with foreign as usual rejecting all themes Americana with $395,000. The $940,000 loss was no more disgraceful than many other Metro releases awash in red ink. Their Mr. Imperium of high hopes and a Broadway opening (as shown here) went down in crushing defeat to $1.4 million lost, but who remembers that? Now well separated from Metro, it seemed Louis Mayer was vindicated in his apprehension over Red Badge and belief that Civil War subjects invariably fail (save for the obvious exception of GWTW). Ironic then was RKO’s release the same month of Drums In The Deep South, a more straight-forward and actionful Blue-Gray engagement, with square-jaws James Craig and Guy Madison far less tentative in the field than Huston’s ragtag army. Trade support and a splashy Atlanta premiere (star Barbara Payton in person!) greeted Drums, but a worldwide rentals total of $1.025 million actually fell slightly below Red Badge. Many public school showings lay in wait for John Huston’s ruined masterpiece (he’d often say the complete version was perhaps the best film he ever made), as state libraries kept it on hand and many a youngster sat for runs in history class. MGM surprisingly withheld Red Badge from its Perpetual Product reissue program in 1962-3, despite "World Heritage" groupings that would have seemed ideal. Television release came in a syndicated package for 1964, with Red Badge among forty titles the highlights of which included On The Town, The Stratton Story, and Love Me Or Leave Me. Revenue from Red Badge syndication totaled $118,000 as of April 1983, plus a "non-prime" network run on the CBS Late Movie which yielded an additional $34,000. By way of comparison, a pre-48 from Metro, Somewhere I’ll Find You, earned $149,000 from syndication through 4-83 and Mrs. Miniver $332,000.