Lou Costello's Fractured Fairy Tale

Here’s something I learned from Bob Furmanek and Ron Palumbo’s Abbott and Costello In The Movies book: A&C signed a five-year deal with NBC in 1951 guaranteeing them fifteen million dollars to do twenty-two half-hour shows on film and four to eight live hour programs during the contract's first year. Over the next four, they would add forty-four TV shows annually, half on film and half live. Now … here’s my question: What did Bud and Lou contemplate filling all those hours with? Material they’d used for Colgate Comedy Hours clicked and led to the rich deal with NBC, but that was mostly burlesque mined since first teaming in the thirties. Gags at Universal had arrived at stale, as were features hosting them, that situation plain to both comedians. Television seems in hindsight to have been the perfect medium for A&C. They still conjured stage patter like no one else. I’d like to have been around for one of their Vegas shows, for I’ll bet these were leagues ahead of anything A&C did in movies. Home tubes were most hospitable to acts needing little more than a backdrop curtain fronted with seltzer-bottles. Complexity beyond that struggled against tiny screens and snowy reception. What if NBC spent some of the fifteen million on fresh writers for Abbott and Costello? Comic minds (Mel Brooks? Carl Reiner?) starting out with rival vid clowns might have given A&C a freshened lease on mirth-making, but could Bud and Lou have transitioned to unplowed fields of comedy, and would viewers have accepted it if they had? Being far removed from live programming of the day (despite surviving kinescopes) robs us of awareness of just how hot the team flashed with TV's beckoning. At that point, it wasn’t necessary for Abbott and Costello to come up with anything new. Home delivery of routines tried-and-true was enough to make them sensations again, but like their meteoric feature rise, it wasn’t built to last. I only have a couple of figures for A&C’s late-model Universal pics, but they must have done alright for continued parceling of them, and the team’s name was sufficient to raise monies for outside ventures permitted under their U-I contract (The Noose Hangs High and Africa Screams as of 1951). Could other teams have finagled loans needed to start and finish a full-length comedy during the late forties/early fifties? The Marx Brothers managed it twice, while Laurel and Hardy had only Euro dollars to back an offshore venture that would be their last. Abbott and Costello got independent-backed work all the way to the end (Dance With Me, Henry) and might have gone on doing so had they remained a team. With such boxoffice capital as they enjoyed in 1951, why shouldn’t Bud and Lou generate Abbott and Costello comedies to call their own?

Bob Thomas wrote in his 1977 team bio that Banker’s Trust fronted cash for Jack and The Beanstalk, a Lou Costello-produced venture to be released by Warner Bros. It was said the latter wanted to do business with A&C, so internal inquiries must have indicated commercial life left in the boys. Costello realized his audience was increasingly kids and planned accordingly. Jack would mimic The Wizard Of Oz and The Blue Bird in all respects but money spent for production values. Its gaudy Super-Cinecolor looked like a Van Beuren cartoon sprung to live action, while singing passages, other than a few by Lou himself, were grindingly bad (Costello personally talent scouted for Jack’s romantic relievers, Shaye Cogan and James Alexander --- neither performed much after this). Bob Thomas says Bud Abbott collected $200,000 as salary against costs of $450,000 incurred by Jack and The Beanstalk. Lou would then receive the same amount for Bud’s production of Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd, to follow within a year. Furmanek/Palumbo offer figures more reliable, to-wit a Jack and The Beanstalk negative cost of $682,580, including $115,000 each for the comedians, leaving $417,742 for the show after A&C's rake-off. Costello for once watched expenditures, as there was more potential profit for him to share in. Stars paying themselves often did so at the expense of what patrons eventually saw. William Boyd’s own Hoppy westerns looked mighty cheap toward the end thanks to monies he pocketed before cameras turned. Lou Costello’s venture lacked surface polish of even their poorest Universal output, which had at least resources of a major studio, even if the best of these were denied A&C comedies. I read of how Jack and The Beanstalk utilized standing sets from Joan Of Arc, a legendary budget-burner shot four to five years previous on rented stages at Hal Roach Studios. For all the pics alleged to have borrowed them, those Joan flats must have gotten pretty threadbare over a seeming decade of low budget re-use.

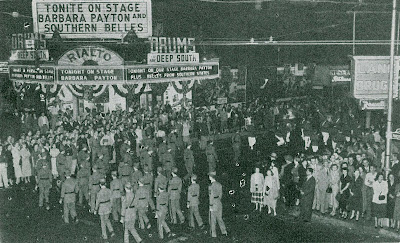

As was often the case, selling trumped producing for effort and energy. To make a picture is one thing, but to go out on the road on a hectic trip to help bring it to the attention of the public is something else again, said Exhibitor magazine in its coverage of the team’s twelve-city tour. Jack and The Beanstalk brought Lou Costello back to hometown Paterson, New Jersey for a premiere momentous beyond rewards to be found in his movie. There were Lion’s Club and Chamber Of Commerce socials to attend, plus checks for varied charities given higher profiles via their acceptance by Abbott and Costello. I wonder what became of all the scrolls and plaques received along the thousands of publicity (and philanthropic) miles (in this case 8,000) these comics traveled. When A&C appeared at your podium, it hardly mattered that their picture wasn’t much good. Ten years of stardom had made indelible brand names of both, and you really get a sense of what that celebrity (and now personal contact) meant to home-folks surrounding Bud and Lou during the Jack tour. As to rental figures, Jack and The Beanstalk collected $1.4 million domestic and $1.1 foreign, more than Abbott-produced Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd, which realized $1.2 million domestic and $892,000 foreign. Warner Brothers seems to have gotten overall better revenues out of A&C than Universal around that period, as U-I’s Abbott and Costello Go To Mars took $1.0 million in domestic rentals and Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde stopped at $979,000 domestic. Lou Costello was said to have "owned" Jack and The Beanstalk, which I assume means the negative, so did his estate allow it to slip into the public domain after an initial twenty-eight years of protection? I’d like to know what became of the negative itself, as what survives on present-day DVD is a port-over of Bob Furmanek’s laser-disc'ed 35mm print, which is striking in its SuperCinecolor, with original sepia opening and closings. That LD for Image is actually the preferred presentation of Jack and The Beanstalk, being loaded with extras unique to the disc, and unlike the DVD, acknowledging Furmanek's effort in presenting it.

I scoured YouTube, without success, for an oddball little subject that used to turn up on American Movie Classics back when that was a network worth watching. It was an inside Hollywood filler produced, I think, by Coy Watson, Jr. A Google search reveals these were made in 1949-50 (called Hollywood Reel) and featured stars engaged in offscreen hobbies and activity. One featured Stan Laurel judging a children’s swim meet. Another segment had Lou Costello showing off … what was it … an icemaker he’d invented? I remember being impressed. Too bad it’s twenty years since seeing it. Did Lou come up with something revolutionary that he never got credit for (or maybe never filed proper patent on)? I’d imagine ongoing royalties on the world’s first icemaker would pay higher than a hundred years of prat-falling in movies, but chances are better I’m just uninformed as to history of icemakers and who initially developed them. It’s just nice to think it might have been Lou Costello. The licking his reputation took (and like Joan Crawford’s, prevails to now) began with publication in 1977 of Bob Thomas’ Bud and Lou, a bio later revealed to have been largely the impressions of soured agent Eddie Sherman, who’d been fired/rehired and generally knocked about by the boys throughout most of their (high) commission-generating careers. For those couple of seasons needed to demolish A&C’s image (mostly Lou’s), there was this book and a scurrilous 1978 TV-movie based on it, also titled Bud and Lou. The one-two punch derailed Costello’s standing as a comic artist and demonized him personally. A persuasive rebuttal came from his daughter Chris in a 1981 memoir. I just read Lou’s On First again and am satisfied Costello got a bum rap from re-imaginers who clearly profited from hoisting him down (Chris got quotes from A&C co-workers who hadn’t spoken before, or since). Indeed, the 70’s might have been about the last decade wherein one could score meaningful publication/movie deals bleaching the bones of Golden Age stars. Three decades further on, it isn’t likely anyone will strike gold in those fields again.