Fatty's Fate and Roscoe's Rescue

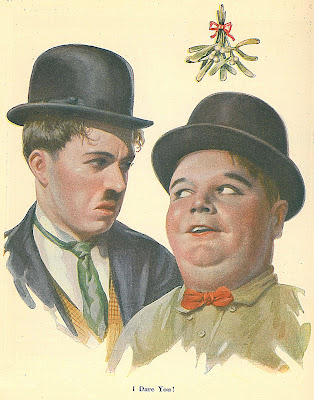

Would that Roscoe Arbuckle’s image were as pristine as this 1919 Pierce-Arrow that once belonged to him! The sleek roadster travels now among auto buffs faintly aware of the forlorn figure pondering his fate on its running board as San Francisco prosecutors sharpened their knives back in September 1921. Leave us face it … Arbuckle is now and will forever be known primarily as tawdry footnote to a period in film history mostly forgotten (challenging enough getting anyone to watch something from the twenties, but the teens?). His comic pioneering seems all the more remote for old rags and hanks of hair that pass for surviving prints. Watch those ghostly figures steeple-jumping over splices and sections missing, then try convincing your doubtful audience that such things once delighted millions. Examine ancient books and periodicals and you’ll find Fatty smiling on every other page. His was the cherubic face people loved (and remember that a heavyweight like him was less common then than now), an oasis of humanity among freakish ensembles populating early comedy. Roscoe's girth was the happier substitute for grotesque mustaches and eyes so heavily made up as to resemble black pools. Kids making their first calls on phones but recently installed would ask exhibitors what funnies they’d be playing, then follow beelines in the event it was Fatty. How many of them cried when he was brought to ruin? So many cheerful images (including this Yule art with Charlie Chaplin) would be banished as if to exorcise an industry of taint Arbuckle was said to have brought upon it. Search for remnants today and chances are you’ll come up empty, as poster survival rate for his films is but a tick above that of pterodactyls. Every stream of Roscoe’s life and accomplishment feeds into that reservoir of tragedy and downfall. He is film history’s reigning underdog, and fans consumed by the injustice won’t rest until Fatty’s out of Coventry and standing equal with comedy’s big three. Would you rank Roscoe with Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd? Having watched most of Laughsmith’s wonderful DVD collection, The Forgotten Films Of Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, I’m inclined toward at least sympathy placement for this saddest of clowns. Nothing’s so fascinating, so compelling, as greatness laid low, and seeing Arbuckle’s output finally celebrated brings him closer (for me) to standing within at least hailing distance of the triumvirate. Should gods of nitrate preservation smile more generously (and a number of his thought-lost films have surfaced over the last ten years), Arbuckle’s reputation may yet scale greater heights. The litanies of what if litter the path of every Arbuckle historian. You’d like to take those forks he missed, for most would have led to a better place for Roscoe. I watch him now and laugh, though images of cruel chance and pitiless fate linger. Should one look to season classic slapstick with real-life loss its practitioners knew, Arbuckle rises quickest to the top, with Keaton, Chaplin, then Lloyd following. Fish for comedy out of such troubled waters and you may find Arbuckle greatest of them all.

Keystone comedies generally start at a run and gain speed from there. People kick and get kicked. They chase and fall down. After awhile, you lose track of who’s being chased and why. Sometimes I’ll twilight during a Keystone and two reels will pass by without me. Mack Sennett emphasized the motion in pictures. Anything standing still made him nervous. Were viewers in 1914 so restless? I’ve read of audiences divided between immigrants and illiterates, packed into refitted storefront ovens generally smelling to high heaven because there was no ventilation. Did these pickled herring laugh at everything they saw? As early Keystones play like one never-ending pursuit extended over hundreds of single reels, you figure a saturation point had to be forthcoming. Roscoe Arbuckle was on the performing road enough years to know he’d need to vary his screen act to keep patrons coming. His weight makes Fatty recognizable in comedies that seldom used close-ups. He is expressive where other faces speed past in blurs. He’d try for moments of subtle pantomime in front of jittery cameras on seeming rubber legs. To appear human in the Keystone universe was accomplishment plenty. People falling off sheer cliffs and walking away from point blank gunshots forfeited audience identification. Arbuckle knew that wouldn’t do. He began directing (under Sennett imposed guidelines) and teamed with Mabel Normand in marital farces. She’d supervised comedies as well, and shared with Roscoe a conviction that the future belonged to characters as opposed to caricatures. Charlie Chaplin’s looming shadow obscured foundations these two laid and rough edges they smoothed. History would credit him for comedy’s emergence out of darkness, but how much of that came of Chaplin’s greater longevity and a better survival rate for his Keystone shorts? Normand’s death in 1930 and Arbuckle’s in 1933 closed the book on a debate that may yet be revived should we come across the dozens of still missing Fatty and Mabel comedies. By 1916, Arbuckle was making his shorts on the East Coast and away from Sennett’s interference. They’re not at a level with what Chaplin was doing for Mutual at the same time, but are plenty good runners-up. Roscoe’s placement as second only to Charlie in popularity polls is borne out by subjects like The Waiter’s Ball and He Did and He Didn’t. The move he’d make to Joseph Schenck’s Comique series would yield comedies even more impressive and partnership for Arbuckle with new to films Buster Keaton.

Again would credit be deflected away from Roscoe, this time in Keaton’s direction. Of twenty comedies Arbuckle made for Schenck (and Paramount release), fourteen also featured Buster. Most were shot in the East. Keaton literally walked in off the street and went to work. He’d been a vaudeville headliner but knew films would be his future. Recruiting comedy’s next genius was Roscoe’s advantage for the two years they’d work together. Writer/director Arbuckle liked everyone to pitch in. His Comiques are far less the insistent one-man shows that Chaplin was doing at Mutual. Fatty’s stock company, other than Keaton, came over with him from Sennett. There was a nephew, Al St. John, to play the menace, and few were so menacing as this apparent escapee from asylum grounds. St. John looked like the demented brother Conrad Nagel kept hidden. Most of his teeth went missing, and ones he had were none too appealing. He always looked dirty. Alice Lake was the girl. Sometimes she’d have lots to do, others she’d be near invisible. Roscoe liked to improvise and welcomed distraction. He’d throw ideas against the wall to see which ones would stick. The earlier Comiques might start off one place and conclude in another, as though a pair of one-reelers had been pasted together. Arbuckle played safe and hewed to Sennett-inspired formula much of the time, only now with bigger budgets he’d empty the whole flour barrel instead of mere face-fulls of it. Roscoe taught Buster but ended up learning more as Keaton quickly mastered film forms. The shorts got better as BK found footing. His hand is evident in gags more evolved than ones Fatty staged at Keystone. Acrobatics on Keaton and St. John's part seem beyond capabilities of mere mortals. Were these men or mythic titans come to life? I swear I saw them fly on more than one breathtaking occasion. Note the beach pyramid here. There’s not an ounce of fat on Buster and Al. Those arms look like steel cable. Fatty’s nickname belied the tower of strength he was. Few men half his size moved so adroitly. Keaton liked to toy with camera tricks and spoof plot conventions others took seriously. Watch The Bell Boy, Good Night Nurse, or Backstage and you’ll see why Buster would later move right into his own starring series for Schenck. Both Keaton and St. John acknowledged Arbuckle as the man who gave them careers in film. Al was said to tear up whenever Roscoe’s name was mentioned. He would go on to starring groups of his own for various companies through the twenties, a trade ad for one of them shown here. Kino and Image have released the Comiques in two competing DVD sets. You’ll need both to get the best viewing experience, as print quality varies from title to title. There are several shorts in the Image box that aren’t available from Kino. The back and forth is well worth your effort in the end, for this is one of the richest groups of silent comedies around.

Joseph M. Schenck bartered Arbuckle to Paramount in much the same way he would Buster Keaton to MGM in 1928. It was time for Roscoe to graduate. He’d work henceforth at corporate headquarters. That meant properties selected for him and directors to whom he’d answer. The retooled Fatty received an astronomical one thousand dollars a day, and would seemingly work twenty-five hours of each. The first eight months saw seven features completed. People wondered how he kept the pace. Roscoe spent his money on cars and hootch and whatever barnacles attached themselves to his star. Paramount promised (or was a better word threatened?) real stories with logical development. Poster copy (shown here) for his first, The Round-Up, read Nobody Loves A Fat Man, chilling prophesy in light of what lay in wait that Labor Day weekend of 1921. Fatty was like a big ripe watermelon waiting to be busted open. The happy caravan snaking into his rooms at the St. Francis found him lubed and vulnerable to all manners of extortion. The sex assault he was said to have inflicted upon sometimes actress Virginia Rappe led to a manslaughter charge after she died several days later. There were multiple trials and Roscoe was acquitted, but tawdry aspects of that party assured public censure and got him off screens nationwide. Notwithstanding criminal charges, the perception of wrongdoing might have been enough to do Roscoe in. Gangsters and tipplers could laugh off the Volstead Act. The rest of us, including picture people, were expected to abide by it. A debauched Fatty in pajamas sipping bootlegged cocktails for breakfast was no fit subject for child viewing. Has any personality paid a higher price for exercising poor judgment than Arbuckle? As to guilt or innocence, modern accounts call it a frame at best and a monstrous act on the part of corrupt authorities. Some of Roscoe’s colleagues disagreed and vilified him to the end. Actress Miriam Cooper was friends with Lowell Sherman, who’d made the fateful drive with Arbuckle to San Francisco and was there for the infamous party. She claimed in a 1973 memoir that Sherman's account as privately conveyed to her and husband Raoul Walsh squarely put blame on Roscoe for Rappe’s death, despite the fact he’d previously gone on record maintaining the comedian’s innocence (I think Lowell was bought off, she said, In fact, I’m sure of it). Pretty damning account, but how reliable were Miriam Cooper’s recollections some fifty years following the event?

Roscoe was shut out of theatres (other than touring vaudeville), but found work directing other comics. Some of these shorts have been unearthed and are part of Laughsmith’s DVD set. All the ones I’ve watched are excellent. I wonder how much participation Arbuckle had in Buster Keaton’s features. He’s said to have helped out on Sherlock, Jr. All nine Paramount features saw release in Europe, outdistancing the scandal that dogged Arbuckle here. Leap Year was among several never shown in the US, but remarkably turned up in Paramount vaults during the late sixties and was turned over to the American Film Institute. It’s more fascinating than funny, and shows the new direction Arbuckle was headed. The comedy is gentler and more situational. You could argue this was just Fatty being polished to a dull sheen, and indeed, if nine such features had been released as scheduled, he’d have been at the least overexposed. Would Roscoe have eventually gained back control of his image and work? It’s likelier he’d have gone on as artist for hire. Arbuckle was never accorded respect Chaplin enjoyed, and had not the business acumen of a Harold Lloyd. One critic summed it up --- Charlie Chaplin is a genius, Roscoe Arbuckle merely a clown. Some will dispute that. Roscoe rescuers say he’s at the least a comic visionary, and they’ve got rediscovered Arbuckle films to back it up. Watch Love, one of his Comique shorts made while Keaton was on a WWI service hitch and you’ll see Roscoe the creator in full flower. By whose standard do we anoint genius in films? It must be a largely subjective one. For whatever reason, I tend to think of Chaplin as a brilliant and hard-working inventor of comedy, while Keaton I consider --- a genius. Roscoe to me is funny and endearing and sometimes inspired. If he were a genius (or if I accepted other’s designation of him as such), I might not enjoy him as much. Look at Fatty’s stuff and he’ll grow on you. I’m wanting someone to release the other Paramount features said to have survived. They include The Round-Up, Life Of The Party, The Traveling Salesman, and Gasoline Gus. A lot of those Comique shorts were considered lost until fairly recently. Their availability has served Roscoe's legacy well, but what of Camping Out, the one most lately found? Is there room in a forthcoming DVD collection for it? I’m optimistic of even more Arbuckle turning up in foreign archives. Any rediscovery is bound to be a happy one. What’s more satisfying than really good comedy seeing projection light again after eighty-five plus years?