You Didn't Have Ice Cream All The Way Through ... --- Part One

I don’t happen to believe that the Marx Brothers sat naked in Irving Thalberg’s office and roasted potatoes, but show business legends die hard, so who am I to spoil everyone’s fun by saying this particular anecdote creeps me out and always has. Still, it dovetails nicely with 60’s era protest gestures applauded in yellowed editions of Ramparts magazine. Maybe Groucho understood this when he repeated the tale for collegiate disciples dogging his senior years. So who among the team’s army of madcap scribes dreamed up this offscreen japery, and when? I’m figuring it was planted in a column just prior to release of A Night At The Opera, or soon thereafter. If the team was to be gelded in front of Metro cameras, then at least preserve some vestige of Marx madness behind them. This viewer enjoyed a boyhood diet limited to their Paramount features. I didn’t come by way of A Night At The Opera until 1973. Funny how you remember best those classics that don’t deliver. At nineteen, I wondered if it was me or the movie. Groucho playing Cupid --- that seemed a violation of everything he stood for. Harpo the happy clown smashes his fingers under a piano lid and gaggles of Metro moppets laugh themselves silly --- sacrilege! Songs, dancing, and romancing. This was the dreaded laxative after a bountiful meal of Duck Soup. So what of the alleged flop of the latter? Did Duck Soup curdle and resolve Paramount to rid itself of Marxes? I don’t have gross figures any more than writers over forty years who’ve accepted received wisdom (itself dating back to columns of the day), but I do have a few for Horse Feathers, and that one was sure enough the company’s number one hit for 1932. At a negative cost of $647,000, the college comedy took a whopping (for 1932) $945,000 in domestic rentals. That was significantly better than runner-ups Shanghai Express ($827,000), The Big Broadcast ($775,000), and Love Me Tonight ($685,000). Co-ed hijinks spiced with Thelma Todd in negligees and a climactic football game would seem a safer bet than political satire, but was Duck Soup a total bust-out? I’m as curious as any Marx fan, and lest Paramount elects to open their ledgers for Greenbriar’s benefit (that’ll be the day), will probably remain so. One elusive number has surfaced, however. Turns out Duck Soup’s negative cost was $765,000. Did Paramount spend themselves into a corner?

Rife had been conflict between stars and studio since Gummo Marx visited from New York and discovered monkey business on the part of Paramount bookkeepers during shooting of the 1931 feature of the same name. Seems they’d forgotten all about profit percentages due the Brothers (after all, Your Profit Is Assured, said Paramount in the above trade ad). The matter simmered through much of 1932 as Gummo sought a proper accounting before inevitable civil actions brought things to a boil. The team then decamped to New York despite preparations being made for Duck Soup. Paramount’s countersuit claimed the Marxes owed them a picture and were refusing to honor their contract. By May 1933, matters was uneasily settled and the comedians, including Groucho and Zeppo (shown with reader identified Gummo aboard the 20th Century Limited here), returned to California to shoot Duck Soup. Overhead was thus piling up before Summer filming began. The Marxes were at least the most expensive comedians on this studio’s payroll. $765,000 exceeded money spent elsewhere on bigger pictures. Consider that MGM had $700,000 in Grand Hotel, Warners managed Golddiggers Of 1933 on a $433,000 negative cost, and RKO finished King Kong for just $672,000. Paramount’s own investment in other comedies was considerably less than Duck Soup. The all-star International House came in at just $337,838. Monies needed to wrap Mae West’s hit I’m No Angel amounted to $434,8000, and W.C. Fields in Tillie and Gus was done for a modest $235,000. The fact is that Paramount, even if it maintained a solid following for its Marx Brothers series, could never hope to profit in the face of expenses like those incurred on Duck Soup. Besides, there were plenty of other laugh-makers on hand to fill the void. Word was out that Duck Soup was a flop, but this wasn’t altogether fair to the Marx Brothers. The long wait of three or so decades to have their final Paramount offering declared one of the greatest sound comedies was hopefully worth it. Groucho acknowledged as much in old age.

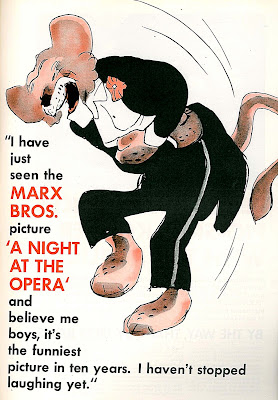

The deal for A Night At The Opera seems to have had its genesis during bridge game conversation between Chico Marx and Irving Thalberg. The comedians had been off movie screens for going on two years and their confidence was shaken. A proposed independent start-up had piled on (financing) rocks, and it was figured the Marxes had lost their momentum. Thalberg made it clear to Groucho that his was a salvage job. These were comedians in need of new direction, and any deal with Metro would be conditioned upon their acceptance of same. Duck Soup was lousy, said Thalberg, to which Groucho could but meekly disagree. I can produce a Marx Brothers comedy with half the laughs that will do twice the business, promised Thalberg. His idea was really nothing new. He’d simply reapply the stage formula used in The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers, only this time romantic subplotters would figure more prominently. There was such a thing as too many laughs, after all. Morrie Ryskind would sum it up while the team was still on Broadway. You didn’t have ice cream all the way through, you know. Feckless stage juveniles had been a necessary conveyance for songs an audience might whistle going home and buy sheet music for the next day. Love stories functioned quite apart from the Marx Brothers and they seldom overlapped. Thalberg was resolved to integrate the two, even if it meant watering down the comedy. This would, at the least, have greater appeal for women. Vulgar and unrelieved laughter was best left to two-reel fillers. A Night At the Opera would deliver on the promise of its title. There would indeed be opera, and per Thalberg’s dictum, we’d take it and like it.

A shame no one referred back to the Paramount model, for they had fixed whatever needed fixing with the Marx Brothers. Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, and Duck Soup ironed out wrinkles inherent in too-literal adaptation of Broadway hits now passé to increasingly sophisticated talkie viewers. Each was better than the one before, with Duck Soup the most polished diamond among them. Thalberg (shown with the team above) and MGM determined to reinvent that wheel. They sent their newly hired comedy team on the road to get live audience confirmation of what exhausted writers hoped might be funny. A half dozen features could have been made from screenplays discarded by Thalberg. How does one honestly know what works after a hundred or so readings and redraftings? One of the writers auditioned some material for his producer. Thalberg scanned the pages without cracking a smile, then turned to the man and announced this is the funniest material I’ve ever read. That story’s been told to Thalberg’s disadvantage, with emphasis on his tin ear for comedy, but many’s the feature and short I’ve watched without outright laughing, yet some rank among favorites for me, evidence I suppose that we don’t necessarily guffaw at everything we find funny. Sometimes an approving smile is expression enough, though comedies shared with a (preferably) large audience do have a way of breaking down inhibition. A Night At The Opera’s live act was fifty minutes of proposed highlights for the feature. They played it four times a day in scattered theatres and spent intervals figuring out what to save for the movie. Audience response determined the keepers. If corporate applied scientific principles got maximum efficiency out of car assembly plants and grocery chains, why not comedy? Thalberg assured control by assigning a humorless functionary to direct. Sam Wood was instructed to shoot repeatedly from every conceivable angle. Thirty or more takes was the enervating norm. The Marx Brothers must have been sick to death of this material once they finally got it all down on film. A Night At The Opera was specifically edited for packed houses. Pauses for laughs break up each routine, much as they would in the later Hope/Crosby road comedies, also designed for large audiences. No wonder some of these play so sluggishly when you’re watching alone.