Jennifer Jones --- Part Two

With Jennifer Jones and David O. Selznick now separated from their respective mates, they could proceed with collaborations that would hopefully confirm Jennifer’s status as the screen’s finest actress. That Selznick elected to do so with Duel In The Sun reflects wildly contradictory impulses that ruled him. It was anybody’s guess as to why he’d set out to produce the world’s most expensive smutty western, but reason and restraint were strangers to DOS, and Duel In The Sun emerged as a lightning rod for censors that surpassed even The Outlaw and Forever Amber. Prissy critics and clergymen felt betrayed by the actress who’d once been their Saint Bernadette, and reviews were withering. All of this was tempered by huge grosses, but so much money had gone into Duel In The Sun that getting it back would take massive infusions of marketing cash. Jennifer’s performance went unrecognized by mainstream critics at the time (though Selznick's campaign did manage to wangle another Academy nomination for his star) --- well, it was just too far ahead of that time --- one of the boldest and most uninhibited turns to come from any actress during the forties. Selznick would dither at other projects. Several started, then stopped. A Little Women with Jennifer would die on the vine, but not before much money was spent amidst months of pre-production and at least several week’s actual shooting. Portrait Of Jennie had to be finished, despite everyone’s conviction that it wasn’t working. Bankers were simply tired of seeing their cash advances go down Selznick ratholes. Jennie was another venture that might better have been abandoned. Good as the finished picture was, it was wildly expensive, and couldn’t hope to get back its negative cost. The ordeal of shooting, and re-shooting, was nearly the death of its leading lady. Reports suggested she tried to jump out a hotel window at one point to escape it all.

Selznick was still a comparatively young man in 1950 (48), but he’d been in the business since silents, having started out with his father as a teenager. Now he felt outmoded and acknowledged as much. It was a business he no longer pretended to understand. Selznick did appreciate the impact of foreign films, however, and supported them by way of production support for The Third Man, which became an unexpected mainstream hit. His idea was to merge the realism of the art pictures with his own Hollywood know-how to create something new in American movies. A collaboration with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger would result in Gone To Earth, another of their Technicolored experiments quite unlike anything else being done in 1950. Jennifer Jones would assure the boxoffice, but Selznick lost his nerve in the eleventh hour and hacked down the completed feature for stateside release. Portions were reshot, much of Powell’s footage was jettisoned, and a new title imposed (The Wild Heart). Still it was deemed unreleasable (scant US distribution several years later confirmed as much). Selznick was undaunted in his quest for a perfect filmmaking marriage between the shores. He financed a neo-realist drama to feature Jennifer under the direction of Vittorio DeSica, one of Italy’s most honored names. White-hot leading man Montgomery Clift would co-star. Again Selznick panicked and Terminal Station was mutilated in post-production. The domestic title, Indiscretion Of An American Wife, emerged with barely enough footage to qualify as a feature. Its utter failure to recoup ($607,000 in domestic rentals) finally convinced Selznick to give up his European experiment. Having served as lure for these risky ventures, Jennifer sought the refuge of a three-picture deal with 20th Fox in the mid-fifties. Her biggest money show of that decade, Love Is A Many-Splendored Thing, would emerge from this group. As for the ignoble Gone To Earth and Terminal Station, both would be exhumed and restored for DVD in the twenty-first century, and both would finally be recognized for the excellent films they always were, before Selznick’s tampering compromised them.

Jennifer Jones might have had a bigger career without Selznick’s interference, but not necessarily a better one. Her resume is stellar --- Since You Went Away, Duel In The Sun, Portrait Of Jennie --- each outstanding. Carrie for director William Wyler was more fine work, but failed largely due to its extraordinarily depressing subject matter (one million in rentals against a negative cost of $2.1). Ruby Gentry was a steamy hit, but Beat The Devil failed. Directors knew they’d be bombarded with Selznick memos should they work with her, and this may have cost the actress jobs. All the while, her husband sought re-entry into active production. A Farewell To Arms in 1957 would bring him back, only this time it was Fox’s money, and their control, not Selznick’s. The resulting disaster was particularly galling, as the studio took what little profit ($365,000) was to be had, leaving Selznick with nothing. Jennifer had been miscast with Rock Hudson. Her age was an issue now, as the part called for a younger actress, and critics felt she’d been imposed upon the project by virtue of her husband’s participation. She might have continued on, but there would be only one more (Tender Is The Night, with losses of four million) before Selznick’s death in 1965.

Jennifer Jones might have had a bigger career without Selznick’s interference, but not necessarily a better one. Her resume is stellar --- Since You Went Away, Duel In The Sun, Portrait Of Jennie --- each outstanding. Carrie for director William Wyler was more fine work, but failed largely due to its extraordinarily depressing subject matter (one million in rentals against a negative cost of $2.1). Ruby Gentry was a steamy hit, but Beat The Devil failed. Directors knew they’d be bombarded with Selznick memos should they work with her, and this may have cost the actress jobs. All the while, her husband sought re-entry into active production. A Farewell To Arms in 1957 would bring him back, only this time it was Fox’s money, and their control, not Selznick’s. The resulting disaster was particularly galling, as the studio took what little profit ($365,000) was to be had, leaving Selznick with nothing. Jennifer had been miscast with Rock Hudson. Her age was an issue now, as the part called for a younger actress, and critics felt she’d been imposed upon the project by virtue of her husband’s participation. She might have continued on, but there would be only one more (Tender Is The Night, with losses of four million) before Selznick’s death in 1965.

Whatever possessed her to do The Idol and Angel, Angel, Down We Go must remain Jennifer’s secret, but neither had many bookings, minimizing embarrassment to some extent. There was another marriage, this time to gadzillionaire Norton Simon, whose obsessive art collecting must surely have evoked Selznickian memories for Jennifer. Both thought it might be good therapy for her to make another movie, but talk about ordeals! The Towering Inferno found the actress dangling off collapsed stairwells and pitching backwards out of scenic elevators (still the biggest shock in the movie). It was as though old Hollywood had been reborn. The all-star cast even locked arms for one of those walking toward the camera publicity shots they used to do back in the days of Libeled Lady and BoomTown. Unlike those last two she’d done, people actually went to see The Towering Inferno, and Jennifer got flattering notices. Maybe it was time to get back in the game. She bought Terms Of Endearment as a vehicle for herself, but was persuaded to cede the leading role to a younger actress (Shirley MacLaine). Norton Simon built an art museum in Pasadena and Jennifer conducted tours. Otherwise, she couldn’t be bothered about her old movies. The Bernadette Oscar was blithely handed over to a hairdresser who admired it (fortunately returned later), and there have been several appearances at Academy Award ceremonies, the most recent being 2003. One would like to think she’d have a change of heart and give us the revealing interview we’ve waited for, but that becomes less likely with each passing year. Maybe there’s just more drama here than she’s comfortable recalling. The fact that Jennifer Jones has survived it all is some kind of remarkable. What a book she could write were she willing.

Photo Captions

Jennifer Jones with Joseph Cotten in Duel In The Sun

With Joseph Cotten in Portrait of Jennie

With Van Heflin in Madame Bovary

Jennifer in Gone To Earth

With Laurence Olivier in Carrie

Jennifer as Ruby Gentry

With Humphrey Bogart in Beat the Devil

With William Holden in Love Is A Many-Splendored Thing

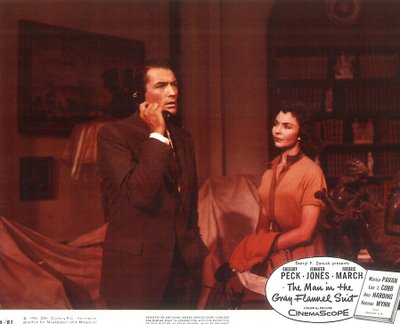

With Gregory Peck in The Man In The Gray Flannel Suit

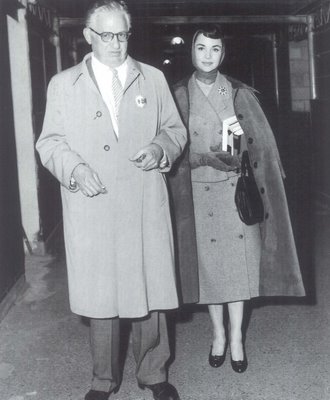

Travelling with husband David O. Selznick

Jennifer in The Towering Inferno