Captains Courageous and Freddie's Liberty No-Show

Captains Courageous and Freddie's Liberty No-Show

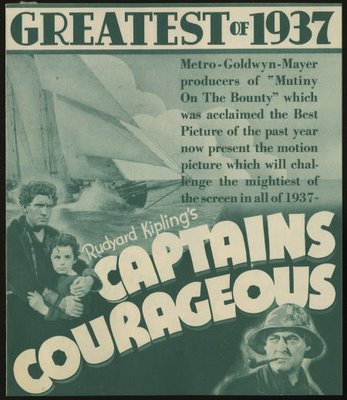

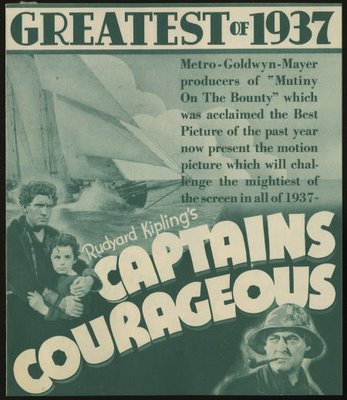

Jason Apuzzo over at LIBERTAS recommended Captains Courageous a week or so ago and I decided to take another look at it. You go for years ignoring pictures like this and they’re always a surprise upon revisiting. C.C. asserted itself often enough in documentaries where that clip of Spencer Tracy singing with an accent played seemingly on a loop. For a lot of people, it summed up the meaning of a classic movie moment. Captains Courageous has long been recognized as Tracy’s picture, but for me, the billing tells the truer story. This is Freddie Bartholomew’s show, and he’s fantastic throughout. I’d forgotten how effective kid actors could be in those days. What a shame Freddie had to grow up, and how unfortunate that MGM dropped him so callously after typecasting the child into a rut during his prime earning years. Audiences react differently to bratty kids in movies. It’s enough for most of us to wait for the character to receive his comeuppance and become a better boy. Sometimes if the youngster is particularly revolting like Jackie Searle or David Holt, we long for him to be punished straightaway, if not killed off altogether. Bartholomew walks that fine line of viewer tolerance, but never crosses it. I was happy to see him fall off the ocean liner, but I didn’t want to see him drown. Is this what separates great child actors from merely competent ones? For such a fine performer, Freddie got a bum deal in American movies. His British propriety looked sissified to many, and some of the roles seemed old-fashioned even then (Little Lord Fauntleroy). I’ll bet there were gangs of boys waiting around stage doors to beat him up after personal appearances. His was the persistent voice of reason that kept scrappier youth like Mickey Rooney and Jackie Cooper out of harm’s way. Too often his character came across as a prig and a party pooper, but more about Freddie later …

Jason Apuzzo over at LIBERTAS recommended Captains Courageous a week or so ago and I decided to take another look at it. You go for years ignoring pictures like this and they’re always a surprise upon revisiting. C.C. asserted itself often enough in documentaries where that clip of Spencer Tracy singing with an accent played seemingly on a loop. For a lot of people, it summed up the meaning of a classic movie moment. Captains Courageous has long been recognized as Tracy’s picture, but for me, the billing tells the truer story. This is Freddie Bartholomew’s show, and he’s fantastic throughout. I’d forgotten how effective kid actors could be in those days. What a shame Freddie had to grow up, and how unfortunate that MGM dropped him so callously after typecasting the child into a rut during his prime earning years. Audiences react differently to bratty kids in movies. It’s enough for most of us to wait for the character to receive his comeuppance and become a better boy. Sometimes if the youngster is particularly revolting like Jackie Searle or David Holt, we long for him to be punished straightaway, if not killed off altogether. Bartholomew walks that fine line of viewer tolerance, but never crosses it. I was happy to see him fall off the ocean liner, but I didn’t want to see him drown. Is this what separates great child actors from merely competent ones? For such a fine performer, Freddie got a bum deal in American movies. His British propriety looked sissified to many, and some of the roles seemed old-fashioned even then (Little Lord Fauntleroy). I’ll bet there were gangs of boys waiting around stage doors to beat him up after personal appearances. His was the persistent voice of reason that kept scrappier youth like Mickey Rooney and Jackie Cooper out of harm’s way. Too often his character came across as a prig and a party pooper, but more about Freddie later …

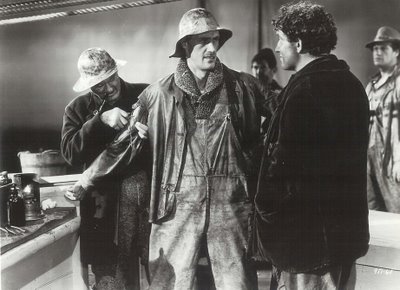

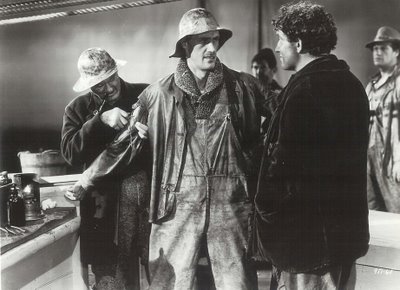

Accents are a curse upon otherwise fine actors. I cringe whenever John Barrymore or Laurence Olivier enter a room and make with the foreign inflections, because you know you’re stuck with it for the run of the feature, and most of the time, that’s agony. Even regional dialects culled from within our own shores can play like broken air-conditioners in a suffocating room. Of the countless southerners I’ve encountered over a life lived in Dixie environs, none have addressed me as Orson Welles does other cast members in The Long, Hot Summer. My query, then, to MGM producers --- Why must Spencer Tracy be Portuguese at all? They’re not shipping out of Portugal in Captains Courageous, and I dare say, fishermen from that country would almost certainly be loathe to go about speaking like Chico Marx. Joan Crawford immediately drew that comparison when she first saw Tracy in costume, and it’s impossible to watch Captains Courageous without making the unfortunate connection. I keep thinking of how powerful Spence could have been if they’d just let him use his natural voice (and that’s director Victor Fleming with the actor on the set of C.C.). As it is, I actually prefer Freddie’s scenes with Lionel Barrymore; indeed this would be one of that actor’s final roles standing up, as within a year he’d be confined to either crutches or a wheelchair. Tracy does become more palatable as the story progresses --- the real Oscar-worthiness of his performance lay in Spence’s ability to overcome the disadvantages inherent in the role (and that ringlet-curled hair!). It may have been the engraver’s idea of a joke when they inscribed the name Dick Tracy on the initial Best Actor award he was given for Captains Courageous, but the more unwelcome gesture came when MGM chief Louis B. Mayer stepped to the podium that night to pay his own acid tribute --- Tracy is a fine actor, but he is most important because he understands why it is necessary to take orders from the front office. Was this a public admonition for the sometimes drink-addled Tracy, whose disappearances from the set had caused production delays and overruns? Captains Courageous actually had a negative cost of 1.6 million, which was considerable money for 1937 (but surprisingly, the same year's A Day At The Races cost even more). Domestic rentals were 1.6 million, with foreign at 1.4. Final profit for the picture was $355,000.

Accents are a curse upon otherwise fine actors. I cringe whenever John Barrymore or Laurence Olivier enter a room and make with the foreign inflections, because you know you’re stuck with it for the run of the feature, and most of the time, that’s agony. Even regional dialects culled from within our own shores can play like broken air-conditioners in a suffocating room. Of the countless southerners I’ve encountered over a life lived in Dixie environs, none have addressed me as Orson Welles does other cast members in The Long, Hot Summer. My query, then, to MGM producers --- Why must Spencer Tracy be Portuguese at all? They’re not shipping out of Portugal in Captains Courageous, and I dare say, fishermen from that country would almost certainly be loathe to go about speaking like Chico Marx. Joan Crawford immediately drew that comparison when she first saw Tracy in costume, and it’s impossible to watch Captains Courageous without making the unfortunate connection. I keep thinking of how powerful Spence could have been if they’d just let him use his natural voice (and that’s director Victor Fleming with the actor on the set of C.C.). As it is, I actually prefer Freddie’s scenes with Lionel Barrymore; indeed this would be one of that actor’s final roles standing up, as within a year he’d be confined to either crutches or a wheelchair. Tracy does become more palatable as the story progresses --- the real Oscar-worthiness of his performance lay in Spence’s ability to overcome the disadvantages inherent in the role (and that ringlet-curled hair!). It may have been the engraver’s idea of a joke when they inscribed the name Dick Tracy on the initial Best Actor award he was given for Captains Courageous, but the more unwelcome gesture came when MGM chief Louis B. Mayer stepped to the podium that night to pay his own acid tribute --- Tracy is a fine actor, but he is most important because he understands why it is necessary to take orders from the front office. Was this a public admonition for the sometimes drink-addled Tracy, whose disappearances from the set had caused production delays and overruns? Captains Courageous actually had a negative cost of 1.6 million, which was considerable money for 1937 (but surprisingly, the same year's A Day At The Races cost even more). Domestic rentals were 1.6 million, with foreign at 1.4. Final profit for the picture was $355,000.

So it’s designated a Family Classic, but would youngsters today be enticed by the likes of Captains Courageous? Initial obstacles are considerable. Black-and-white, for one thing, but that Warners DVD is sufficiently rich to hopefully overcome at least some of that prejudice. Otherwise, I think it may still work with kids. Has anyone tried it on theirs? Any film that traffics in emotional content like this is a gamble by definition. Chances are they’ll laugh or dismiss it as hopelessly maudlin pap (but who knew they'd shot that final sequence in front of Andy Hardy's house as this backlot candid reveals ...). How many movies today deal (seriously) with coming of age subjects? Father-son alienation and reconciliation? You have to admire anyone’s sheer audacity in playing such material straight, for there’s nothing I can think of that’s harder to pull off. If this kind of sentiment works even for an instant, all else is forgiven and you’ve got a picture that will be admired and warmly remembered. I’ve read accounts of those who saw Captains Courageous first-run and never forgot the impact. We can’t know what it was like for audiences in 1937, but after watching that DVD last week, I could guess. This is yet another of those movies you think you’re seeing from an objective distance until one little moment comes along and there you are with the same tear in your eye that the rest of them dabbed away nearly seventy years ago. Any picture that can deliver even so fleeting a glow is well worth cherishing.

So it’s designated a Family Classic, but would youngsters today be enticed by the likes of Captains Courageous? Initial obstacles are considerable. Black-and-white, for one thing, but that Warners DVD is sufficiently rich to hopefully overcome at least some of that prejudice. Otherwise, I think it may still work with kids. Has anyone tried it on theirs? Any film that traffics in emotional content like this is a gamble by definition. Chances are they’ll laugh or dismiss it as hopelessly maudlin pap (but who knew they'd shot that final sequence in front of Andy Hardy's house as this backlot candid reveals ...). How many movies today deal (seriously) with coming of age subjects? Father-son alienation and reconciliation? You have to admire anyone’s sheer audacity in playing such material straight, for there’s nothing I can think of that’s harder to pull off. If this kind of sentiment works even for an instant, all else is forgiven and you’ve got a picture that will be admired and warmly remembered. I’ve read accounts of those who saw Captains Courageous first-run and never forgot the impact. We can’t know what it was like for audiences in 1937, but after watching that DVD last week, I could guess. This is yet another of those movies you think you’re seeing from an objective distance until one little moment comes along and there you are with the same tear in your eye that the rest of them dabbed away nearly seventy years ago. Any picture that can deliver even so fleeting a glow is well worth cherishing.

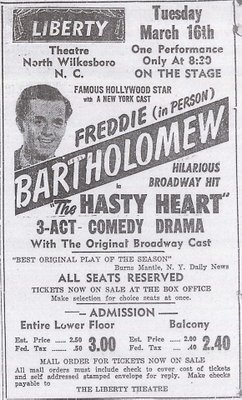

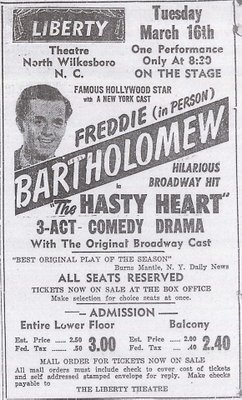

Back to Freddie. Long after the world’s applause had subsided, FreddieBartholomew took to the road a six-foot gangly stage hopeful in a stock version of The Hasty Heart during the Spring of 1948. It seemed incredible that David Copperfield himself would turn up in a backwoods jerkwater town like ours, but Liberty owner Ivan Anderson and his manager Colonel Roy Forehand weren’t kidding when they advertised Bartholomew and the original Broadway cast for one performance only on March 16. Rest assured these admission prices ($3.00 for the lower floor!) were quite unheard of in a town where big-time stage attractions usually amounted to no-name bands, hillbilly singers, and sometime cowboy sidekicks (previously reported on HERE). Mail order tickets were something I never experienced at the Liberty in all my years going there. Truly this was the season event for 1948 … and then it got cancelled. The specifics of what happened are lost in the mists of time, but Mr. Anderson was determined to get back the $1,592.37 in lost revenue (mostly those advance tickets he had to make good on). Toward that end, he filed a lawsuit against the stage company after tracing their whereabouts to Savannah, Georgia, where lawyers on behalf of the Liberty Theatre impounded all the props and costumes for The Hasty Heart. The defendant was identified as one Larry Lerouge, representing Imperial Players out of New York. By this time, Freddie had repaired to his hotel digs, having lost a tooth filling. Freddie has played shows when he had a fever of 103 and a cracked rib, said his chagrined wife when advised the show may not go on, and shortly after Freddie defended his own thespic honor by declaring this was merely an argument between theatres and managers having nothing to do with him. With regards the final outcome, I’ve no idea as to whether Mr. Anderson got his money back, though I suspect a few of those ticket holders may still be waiting to see The Hasty Heart on the Liberty’s stage …

Back to Freddie. Long after the world’s applause had subsided, FreddieBartholomew took to the road a six-foot gangly stage hopeful in a stock version of The Hasty Heart during the Spring of 1948. It seemed incredible that David Copperfield himself would turn up in a backwoods jerkwater town like ours, but Liberty owner Ivan Anderson and his manager Colonel Roy Forehand weren’t kidding when they advertised Bartholomew and the original Broadway cast for one performance only on March 16. Rest assured these admission prices ($3.00 for the lower floor!) were quite unheard of in a town where big-time stage attractions usually amounted to no-name bands, hillbilly singers, and sometime cowboy sidekicks (previously reported on HERE). Mail order tickets were something I never experienced at the Liberty in all my years going there. Truly this was the season event for 1948 … and then it got cancelled. The specifics of what happened are lost in the mists of time, but Mr. Anderson was determined to get back the $1,592.37 in lost revenue (mostly those advance tickets he had to make good on). Toward that end, he filed a lawsuit against the stage company after tracing their whereabouts to Savannah, Georgia, where lawyers on behalf of the Liberty Theatre impounded all the props and costumes for The Hasty Heart. The defendant was identified as one Larry Lerouge, representing Imperial Players out of New York. By this time, Freddie had repaired to his hotel digs, having lost a tooth filling. Freddie has played shows when he had a fever of 103 and a cracked rib, said his chagrined wife when advised the show may not go on, and shortly after Freddie defended his own thespic honor by declaring this was merely an argument between theatres and managers having nothing to do with him. With regards the final outcome, I’ve no idea as to whether Mr. Anderson got his money back, though I suspect a few of those ticket holders may still be waiting to see The Hasty Heart on the Liberty’s stage …

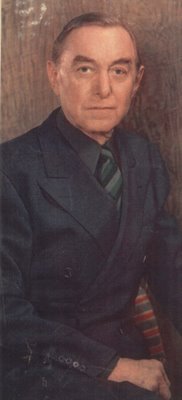

Monday Glamour Starter --- Evelyn KeyesEvelyn Keyes is one of those hardy survivors of the Golden Age who’s gotten to outlive other members of her club, becoming a sort of gatekeeper between here and eternity. Our modern day perceptions of classic Hollywood are based largely on what folks like Evelyn have had to say about it. If you stay around long enough in this business, you get to write the history for those of us too young to have known it first hand. For some old-timers, that’s an opportunity to settle scores of long standing and serve themselves at the expense of those who can’t answer back, but Evelyn Keyes strikes me as one of the more clear-headed and reliable diarists of that era. For most people, she provides an affirmative answer to the age-old trivia question, Who’s left from Gone With the Wind? For years, Evelyn Keyes signed whatever mementos turned up in her mailbox and sent them back … gratis. About ten years ago, requests (and photos) began returning to fans with a form demand of twenty-five dollars for each autograph. Well, if Evelyn’s going to outlast the rest of that legendary group, why should she spend all that time helping "Windies" (her phrase) bolster up their collections on a movie she made back in 1939? That question’s been lately rendered moot by health circumstances that have confined this once-dynamic veteran to a nursing facility, where she’s currently residing at age 89.

Monday Glamour Starter --- Evelyn KeyesEvelyn Keyes is one of those hardy survivors of the Golden Age who’s gotten to outlive other members of her club, becoming a sort of gatekeeper between here and eternity. Our modern day perceptions of classic Hollywood are based largely on what folks like Evelyn have had to say about it. If you stay around long enough in this business, you get to write the history for those of us too young to have known it first hand. For some old-timers, that’s an opportunity to settle scores of long standing and serve themselves at the expense of those who can’t answer back, but Evelyn Keyes strikes me as one of the more clear-headed and reliable diarists of that era. For most people, she provides an affirmative answer to the age-old trivia question, Who’s left from Gone With the Wind? For years, Evelyn Keyes signed whatever mementos turned up in her mailbox and sent them back … gratis. About ten years ago, requests (and photos) began returning to fans with a form demand of twenty-five dollars for each autograph. Well, if Evelyn’s going to outlast the rest of that legendary group, why should she spend all that time helping "Windies" (her phrase) bolster up their collections on a movie she made back in 1939? That question’s been lately rendered moot by health circumstances that have confined this once-dynamic veteran to a nursing facility, where she’s currently residing at age 89.

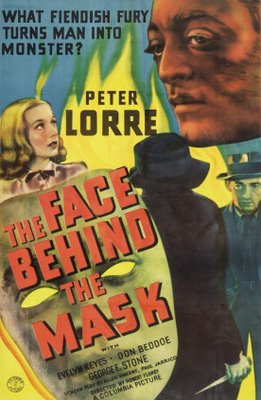

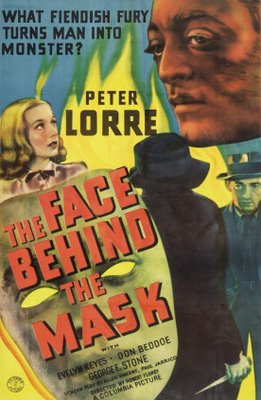

It wasn’t the movies she did, but the friends she made, that inspire our interest in Evelyn Keyes today. Her 1977 autobiography, Scarlett O'Hara's Younger Sister: My Lively Life in and Out of Hollywood, is a randy tome chock full of wild and wooly anecdotes of fast-lane encounters with industry men of the world who bedded and (sometimes) married her. These swimsuit poses go at least part of the way toward explaining what attracted John Huston, Charles Vidor, Michael Todd, and Artie Shaw, but there’s an intellect at work in this book that better accounts for her presence alongside filmland’s best and brightest of that era (and you can pick up a used copy on Amazon for one penny, according to current listings). If she’d worked somewhere other than Columbia, Evelyn Keyes might have become a bigger name, but few stars emerged from Gower Street, and she stymied whatever chance she might have had at that modest address when she rebuffed the crude advances of studio boss Harry Cohn. Once the applause died down for her biggest personal success, The Jolson Story, Cohn assured Keyes she’d never be a bigger star than she was at that moment, and he seemed to have made good on the promise by consigning her to what appeared to be low-grade crime thrillers coming off late 40’s/early 50’s assembly lines. The happy irony lay in the fact that these would become some of the most notable features on her credits list --- The Killer That Stalked New York, The Prowler, 99 River Street, etc. --- a circumstance that led to Keyes’ inclusion among noir names featured in Eddie Muller’s excellent interview collection, Dark City Dames (available HERE).

It wasn’t the movies she did, but the friends she made, that inspire our interest in Evelyn Keyes today. Her 1977 autobiography, Scarlett O'Hara's Younger Sister: My Lively Life in and Out of Hollywood, is a randy tome chock full of wild and wooly anecdotes of fast-lane encounters with industry men of the world who bedded and (sometimes) married her. These swimsuit poses go at least part of the way toward explaining what attracted John Huston, Charles Vidor, Michael Todd, and Artie Shaw, but there’s an intellect at work in this book that better accounts for her presence alongside filmland’s best and brightest of that era (and you can pick up a used copy on Amazon for one penny, according to current listings). If she’d worked somewhere other than Columbia, Evelyn Keyes might have become a bigger name, but few stars emerged from Gower Street, and she stymied whatever chance she might have had at that modest address when she rebuffed the crude advances of studio boss Harry Cohn. Once the applause died down for her biggest personal success, The Jolson Story, Cohn assured Keyes she’d never be a bigger star than she was at that moment, and he seemed to have made good on the promise by consigning her to what appeared to be low-grade crime thrillers coming off late 40’s/early 50’s assembly lines. The happy irony lay in the fact that these would become some of the most notable features on her credits list --- The Killer That Stalked New York, The Prowler, 99 River Street, etc. --- a circumstance that led to Keyes’ inclusion among noir names featured in Eddie Muller’s excellent interview collection, Dark City Dames (available HERE).

After so many years fielding endless questions about Gone With the Wind, it must have been refreshing to finally take bows for those noir titles, but again, this is an actress who’s been around long enough to see one vogue discarded in favor of another. Publishers had imposed that book title on her. GWTW was still riding a crest of latter-day popularity in 1977, having recently had its television premiere on NBC. Any connection between Evelyn’s memoirs and the movie would assure sales. The thirty years since then have not been kind to Gone With the Wind. The one time theatrical stalwart that remained exclusive to big screens for nearly four decades is now filler on TCM. All the plates, dolls, limited-edition collectibles and so forth that drove the nostalgia market during the seventies and eighties have gone in search of other idols to worship, and the prospect of Gone With the Wind achieving such singular prominence again seems less likely with each passing year. Worth noting is the fact that Scarlett’s two younger sisters (Evelyn and Ann Rutherford) will have outlived her by forty years as of 2007 (Vivien Leigh having died in 1967).

After so many years fielding endless questions about Gone With the Wind, it must have been refreshing to finally take bows for those noir titles, but again, this is an actress who’s been around long enough to see one vogue discarded in favor of another. Publishers had imposed that book title on her. GWTW was still riding a crest of latter-day popularity in 1977, having recently had its television premiere on NBC. Any connection between Evelyn’s memoirs and the movie would assure sales. The thirty years since then have not been kind to Gone With the Wind. The one time theatrical stalwart that remained exclusive to big screens for nearly four decades is now filler on TCM. All the plates, dolls, limited-edition collectibles and so forth that drove the nostalgia market during the seventies and eighties have gone in search of other idols to worship, and the prospect of Gone With the Wind achieving such singular prominence again seems less likely with each passing year. Worth noting is the fact that Scarlett’s two younger sisters (Evelyn and Ann Rutherford) will have outlived her by forty years as of 2007 (Vivien Leigh having died in 1967).

I’d read that Evelyn Keyes was companion to producer Michael Todd between 1953 and 1956, but I hadn’t realized she was also involved in the financing and promotion of Around The World In 80 Days. This is one Best Picture award winner universally reviled today, proof positive, as if more were needed, that Oscars are bought, not earned (though personally, I kinda like it). Todd seems to have financed this extravaganza on a week-by-week basis, and the life he shared with Evelyn usually revolved around hustle dinners where some clueless investor was gathered into the net. It was inevitable that Keyes herself would be snookered as well, but this deal differed in that Todd pledged five percent of Around The World In 80 Days to Keyes in exchange for $25,000 and her continuing efforts on behalf of the picture. The 32.8 million worldwide rentals eventually realized from the show made a lot of people rich, but not Evelyn, who by then had split with Michael Todd. By the time she smelled a rat, he’d perished in a plane crash over New Mexico and her five percent was something estate lawyers, working at the behest of Todd’s son, had no interest in discussing. The protracted lawsuit finally paid out, but for less than Evelyn had coming. She was so dispirited by the whole experience that it was enough just to salvage something from the ordeal and move on. A final marriage to one-time musician Artie Shaw was complicated by his (extreme) temperament, and once again, there was a deal between the two that put Keyes back into litigation in the wake of his death just two years ago. Their agreement had called for each to inherit the estate of the other, whichever died first, and never mind the fact they’d been divorced since the eighties. Evelyn was probably not aware of the court action on her behalf, having relocated for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Actor and friend Tab Hunter has assisted with her affairs since that time, and according to wire reports, she did receive the compensation due her from Shaw’s estate.Photo CaptionsEvelyn Keyes and Ann Ritherford arrive at the Selznick lot to shoot Gone With The WindSwimsuit Publicity for Columbia PicturesWith Olivia DeHavilland and Ann Rutherford in Gone With The WindWith Bruce Bennett in Before I HangWith Rita Johnson and Robert Montgomery in Here Comes Mr. JordanOne-Sheet and Lobby Card for The Face Behind The MaskMore Swimsuit PublicityWith Dick Powell in Johnny O'ClockThe Killer That Stalked New YorkWith Van Heflin in The ProwlerWith John Payne in 99 River Street

I’d read that Evelyn Keyes was companion to producer Michael Todd between 1953 and 1956, but I hadn’t realized she was also involved in the financing and promotion of Around The World In 80 Days. This is one Best Picture award winner universally reviled today, proof positive, as if more were needed, that Oscars are bought, not earned (though personally, I kinda like it). Todd seems to have financed this extravaganza on a week-by-week basis, and the life he shared with Evelyn usually revolved around hustle dinners where some clueless investor was gathered into the net. It was inevitable that Keyes herself would be snookered as well, but this deal differed in that Todd pledged five percent of Around The World In 80 Days to Keyes in exchange for $25,000 and her continuing efforts on behalf of the picture. The 32.8 million worldwide rentals eventually realized from the show made a lot of people rich, but not Evelyn, who by then had split with Michael Todd. By the time she smelled a rat, he’d perished in a plane crash over New Mexico and her five percent was something estate lawyers, working at the behest of Todd’s son, had no interest in discussing. The protracted lawsuit finally paid out, but for less than Evelyn had coming. She was so dispirited by the whole experience that it was enough just to salvage something from the ordeal and move on. A final marriage to one-time musician Artie Shaw was complicated by his (extreme) temperament, and once again, there was a deal between the two that put Keyes back into litigation in the wake of his death just two years ago. Their agreement had called for each to inherit the estate of the other, whichever died first, and never mind the fact they’d been divorced since the eighties. Evelyn was probably not aware of the court action on her behalf, having relocated for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Actor and friend Tab Hunter has assisted with her affairs since that time, and according to wire reports, she did receive the compensation due her from Shaw’s estate.Photo CaptionsEvelyn Keyes and Ann Ritherford arrive at the Selznick lot to shoot Gone With The WindSwimsuit Publicity for Columbia PicturesWith Olivia DeHavilland and Ann Rutherford in Gone With The WindWith Bruce Bennett in Before I HangWith Rita Johnson and Robert Montgomery in Here Comes Mr. JordanOne-Sheet and Lobby Card for The Face Behind The MaskMore Swimsuit PublicityWith Dick Powell in Johnny O'ClockThe Killer That Stalked New YorkWith Van Heflin in The ProwlerWith John Payne in 99 River Street

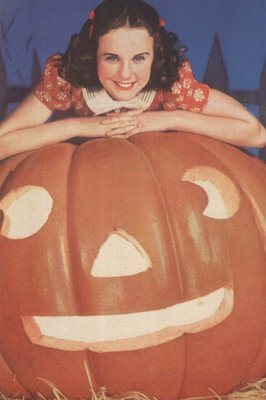

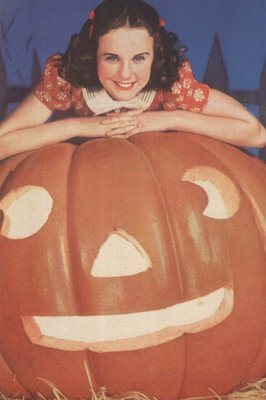

They're Autumn Appropriate, So Here They AreWith Halloween only days off, it's only fitting that we recognize a few seasonal shots that were part of ongoing publicity efforts by the studios. Every actress eventually found herself in the company of black cats, jack-o-lanterns, and what not. Within the month, a turkey or Pilgrim pose would be on their schedule. Someone should do a compilation of Christmas themed stills. There must be thousands of them. I'll surely be digging out a few for Greenbriar this December. In the meantime, here's Deanna Durbin and Gloria DeHaven celebrating the Fall season.

They're Autumn Appropriate, So Here They AreWith Halloween only days off, it's only fitting that we recognize a few seasonal shots that were part of ongoing publicity efforts by the studios. Every actress eventually found herself in the company of black cats, jack-o-lanterns, and what not. Within the month, a turkey or Pilgrim pose would be on their schedule. Someone should do a compilation of Christmas themed stills. There must be thousands of them. I'll surely be digging out a few for Greenbriar this December. In the meantime, here's Deanna Durbin and Gloria DeHaven celebrating the Fall season.

Fox Starlets In RevueHere are five Twentieth-Century Fox hopefuls around 1943. From the left, there is June Haver, who had a number of leads in musicals before entering a convent (!), which she soon abandoned to marry Fred MacMurray (!!). Mary Anderson had been in Gone With The Wind before she was twenty. Her Fox appearances included Lifeboat, The Song Of Bernadette, and Wilson. It would appear she’s still with us, at age 86. Gale Robbins seems to have made only one Fox picture during this period, In The Meantime, Darling, which was a starring vehicle for Jeanne Crain, by far the biggest name in this group. There was a brief moment during the mid-forties when she was the hottest property on the lot, thanks to shows like Margie and State Fair. Trudy Marshall is best remembered for having worked with Laurel and Hardy in The Dancing Masters. That credit gave her a seat of honor at a number of Sons Of The Desert gatherings.

Fox Starlets In RevueHere are five Twentieth-Century Fox hopefuls around 1943. From the left, there is June Haver, who had a number of leads in musicals before entering a convent (!), which she soon abandoned to marry Fred MacMurray (!!). Mary Anderson had been in Gone With The Wind before she was twenty. Her Fox appearances included Lifeboat, The Song Of Bernadette, and Wilson. It would appear she’s still with us, at age 86. Gale Robbins seems to have made only one Fox picture during this period, In The Meantime, Darling, which was a starring vehicle for Jeanne Crain, by far the biggest name in this group. There was a brief moment during the mid-forties when she was the hottest property on the lot, thanks to shows like Margie and State Fair. Trudy Marshall is best remembered for having worked with Laurel and Hardy in The Dancing Masters. That credit gave her a seat of honor at a number of Sons Of The Desert gatherings.

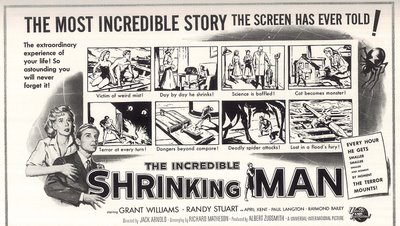

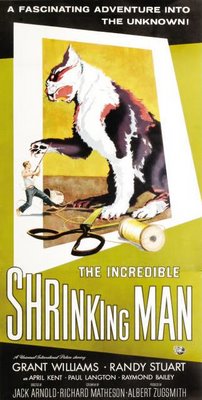

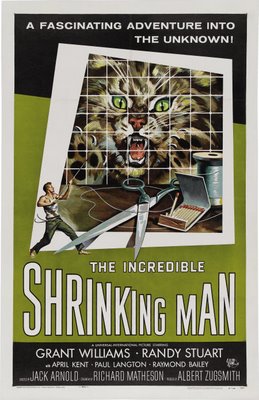

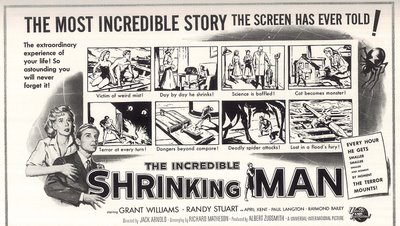

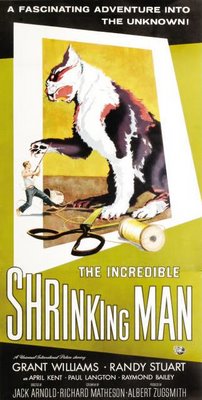

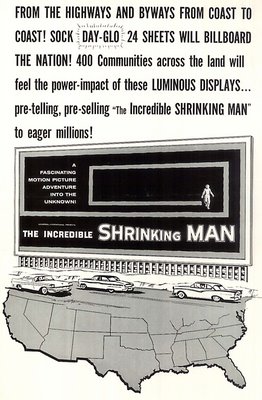

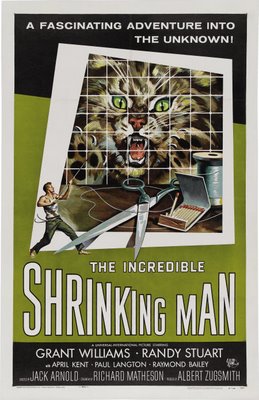

The Incredibly Unsettling Shrinking Man

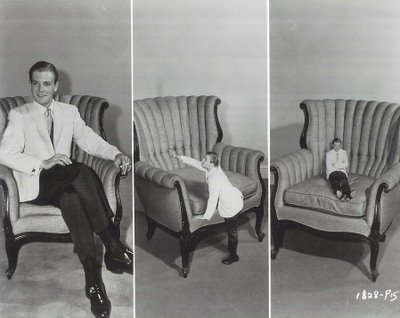

The Incredibly Unsettling Shrinking Man There used to be a cat in the yard that I shared with a neighbor. We’d take turns feeding it, which sometimes yielded four or so meals a day. Being a natural predator, T.C. (their name for him --- mine was Satan) would drag his belly over the grass in search of yet more food, usually field mice. On one occasion, I watched T.C./Satan presiding over the slow death of a rodent he’d captured in the yard, knowing full well that were I shrunken to that diminutive size, the cat I served each day would happily and unhesitatingly feed upon me. In short, I’d be Scott Carey! That frightful image of a tiny man fleeing his own ravenous pet has endured in the hearts and minds of all those who saw The Incredible Shrinking Man at an impressionable age. I had lunch last week with a longtime friend who’s now a District Court Judge. He experienced it the same day as I, in July of 1964, on a double feature with Jack The Giant Killer. His astonishing recall of that Saturday so many years ago, and the details he related, confirmed this as having been the most horrific movie encounter that six-year-old ever had. For myself, ten at the time, The Incredible Shrinking Man touched nerves hitherto impervious to the likes of Konga, Tarantula, or even The Amazing Colossal Man, for this was clearly science-fiction not to be laughed at. I was quite unprepared for that sobering finish. Shrinking Man may have been the first occasion for a whole generation of kids to ponder larger life issues Grant Williams submits for our consideration as he shrinks to infinity. What I failed to recognize then was just how effectively The Incredible Shrinking Man tapped into adult fears as well, for this was really a movie about terminal illness and slow death, subjects mainstream Hollywood loathed to address, but ones that might be concealed deep within the framework of a modestly budgeted sci-fi movie.

There used to be a cat in the yard that I shared with a neighbor. We’d take turns feeding it, which sometimes yielded four or so meals a day. Being a natural predator, T.C. (their name for him --- mine was Satan) would drag his belly over the grass in search of yet more food, usually field mice. On one occasion, I watched T.C./Satan presiding over the slow death of a rodent he’d captured in the yard, knowing full well that were I shrunken to that diminutive size, the cat I served each day would happily and unhesitatingly feed upon me. In short, I’d be Scott Carey! That frightful image of a tiny man fleeing his own ravenous pet has endured in the hearts and minds of all those who saw The Incredible Shrinking Man at an impressionable age. I had lunch last week with a longtime friend who’s now a District Court Judge. He experienced it the same day as I, in July of 1964, on a double feature with Jack The Giant Killer. His astonishing recall of that Saturday so many years ago, and the details he related, confirmed this as having been the most horrific movie encounter that six-year-old ever had. For myself, ten at the time, The Incredible Shrinking Man touched nerves hitherto impervious to the likes of Konga, Tarantula, or even The Amazing Colossal Man, for this was clearly science-fiction not to be laughed at. I was quite unprepared for that sobering finish. Shrinking Man may have been the first occasion for a whole generation of kids to ponder larger life issues Grant Williams submits for our consideration as he shrinks to infinity. What I failed to recognize then was just how effectively The Incredible Shrinking Man tapped into adult fears as well, for this was really a movie about terminal illness and slow death, subjects mainstream Hollywood loathed to address, but ones that might be concealed deep within the framework of a modestly budgeted sci-fi movie.

All this came home to me when I watched the new DVD last week. I’ve had several friends lately who’ve gotten bad news from doctors. That happens as one gets older. Each time, you wonder when it’s going to be your turn. Scott Carey’s ordeal was no different in its essentials from a negative prognosis any of us might receive. However this movie may have dated since 1957, this is one aspect that hasn’t. Children watching The Incredible Shrinking Man need only worry about cats and spiders. For adults, there are grimmer possibilities, and they can’t be resolved with a knitting needle. Is this why I hesitated to watch it again? I’d challenge anyone who calls this a "fun" movie. That’s a domain for giant ants, Creatures from lagoons, and Metaluna mutants. They offer escapes from life, not confrontations with death. Monsters kill people in sci-fi movies and it doesn’t bother us. Scott Carey loses hope for recovery and it’s shattering. We’re all of us reasonably safe from attack by a rampaging stegosaurus, but what about that biopsy result that’s due back? It’s difficult in middle age to watch The Incredible Shrinking Man and not imagine yourself standing naked and vulnerable in a doctor's office. There are few movies so clinical in their depiction of a man doomed. The underlying theme is even spelled out when specialist Raymond Bailey refers to the anti-cancer causing a diminution of all organs proportionately, while the fear of abandonment during one’s final illness is slammed home in that unbearably sad moment with the wedding ring. Unlike a lot of movies that ultimately pull their punches, this one follows through on its despairing promise, for Scott will indeed be abandoned in the end.

All this came home to me when I watched the new DVD last week. I’ve had several friends lately who’ve gotten bad news from doctors. That happens as one gets older. Each time, you wonder when it’s going to be your turn. Scott Carey’s ordeal was no different in its essentials from a negative prognosis any of us might receive. However this movie may have dated since 1957, this is one aspect that hasn’t. Children watching The Incredible Shrinking Man need only worry about cats and spiders. For adults, there are grimmer possibilities, and they can’t be resolved with a knitting needle. Is this why I hesitated to watch it again? I’d challenge anyone who calls this a "fun" movie. That’s a domain for giant ants, Creatures from lagoons, and Metaluna mutants. They offer escapes from life, not confrontations with death. Monsters kill people in sci-fi movies and it doesn’t bother us. Scott Carey loses hope for recovery and it’s shattering. We’re all of us reasonably safe from attack by a rampaging stegosaurus, but what about that biopsy result that’s due back? It’s difficult in middle age to watch The Incredible Shrinking Man and not imagine yourself standing naked and vulnerable in a doctor's office. There are few movies so clinical in their depiction of a man doomed. The underlying theme is even spelled out when specialist Raymond Bailey refers to the anti-cancer causing a diminution of all organs proportionately, while the fear of abandonment during one’s final illness is slammed home in that unbearably sad moment with the wedding ring. Unlike a lot of movies that ultimately pull their punches, this one follows through on its despairing promise, for Scott will indeed be abandoned in the end.

Now about that spider scene. There have been noises among online discussion groups that some of it may have been trimmed from the DVD. You'll recall the noxious creature hovers over Grant Williams for what seems an eternity before being impaled by his intended victim. The flow of blood that spews from the monster’s wound still inspires universal (and international) cringing among audience members. Posted complaints said there was much more blood in theatrical prints, but could these rose (or crimson) colored memories be an exaggeration of what we really saw? I can only relate the moment as it unspooled before me in 1964: The spider was preparing to seize Grant in its fearsome jaws. Grant thrust the needle into that soft belly. Torrents of blood gushed out. It not only covered Grant’s arm, but his entire body. The man was drenched. He had to swim through this muck as the beast’s foul carcass threatened to settle upon him. It was the most violent and explicit sequence in the entire history of motion pictures. The Liberty’s 35mm print was seized by federal authorities and offending footage removed by editors equipped with sidearms. No one has seen it since. How’s that for an enhanced recollection? Minus the gory river, armed officials, and disappearing reel, here’s what I do remember --- Yes, there was a little more blood in the scene and some of it ran down Grant William’s arm and on to his chest. Did I actually see it, or is this too an embellishment, albeit an unintended one? This is one movie argument that will never be settled.

Now about that spider scene. There have been noises among online discussion groups that some of it may have been trimmed from the DVD. You'll recall the noxious creature hovers over Grant Williams for what seems an eternity before being impaled by his intended victim. The flow of blood that spews from the monster’s wound still inspires universal (and international) cringing among audience members. Posted complaints said there was much more blood in theatrical prints, but could these rose (or crimson) colored memories be an exaggeration of what we really saw? I can only relate the moment as it unspooled before me in 1964: The spider was preparing to seize Grant in its fearsome jaws. Grant thrust the needle into that soft belly. Torrents of blood gushed out. It not only covered Grant’s arm, but his entire body. The man was drenched. He had to swim through this muck as the beast’s foul carcass threatened to settle upon him. It was the most violent and explicit sequence in the entire history of motion pictures. The Liberty’s 35mm print was seized by federal authorities and offending footage removed by editors equipped with sidearms. No one has seen it since. How’s that for an enhanced recollection? Minus the gory river, armed officials, and disappearing reel, here’s what I do remember --- Yes, there was a little more blood in the scene and some of it ran down Grant William’s arm and on to his chest. Did I actually see it, or is this too an embellishment, albeit an unintended one? This is one movie argument that will never be settled.

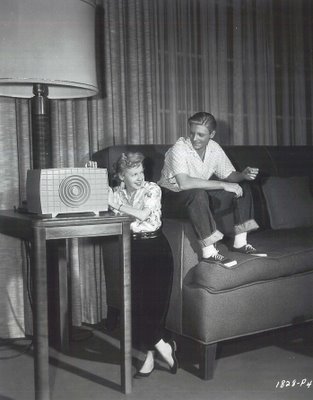

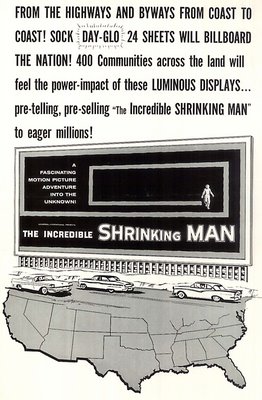

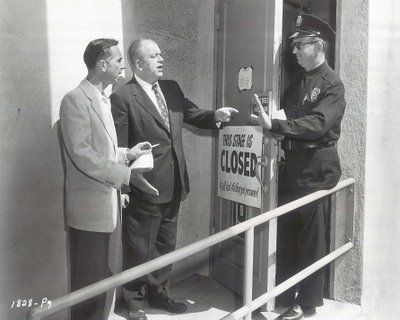

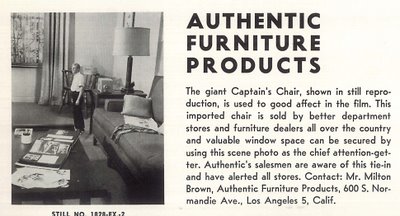

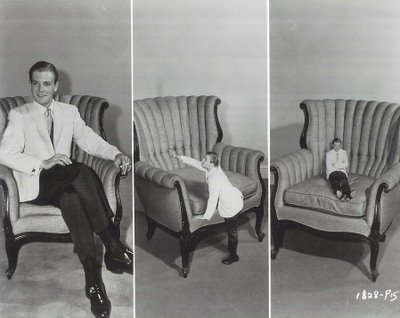

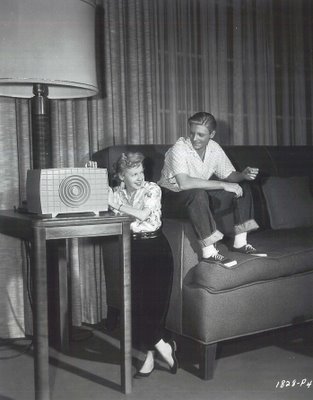

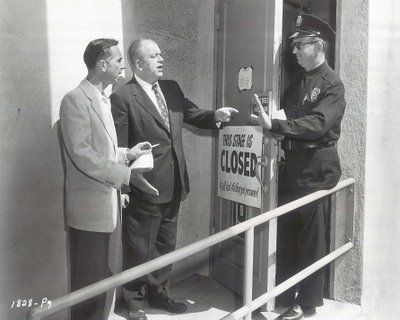

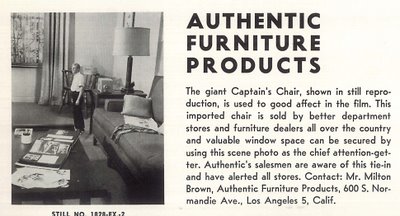

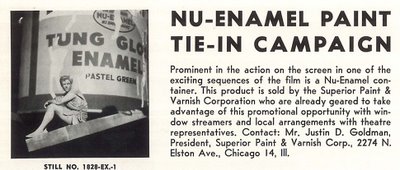

What a great still of director Jack Arnold and producer Albert Zugsmith being denied access to the Shrinking Man set! Why don’t they do shots like this anymore? Must current movies take themselves so seriously? Zuggy was hanging his hat at Universal during the mid to late fifties, and some of the credits he accumulated were pretty impressive. Written On The Wind, The Tarnished Angels (was Zugsmith the real architect behind that fabled Sirkian touch?), Man In The Shadow (Jeff Chandler as a conflicted western sheriff!), Star In the Dust (John Agar as a conflicted western sheriff!), and TOUCH OF EVIL!! Do we owe Orson Welles’ mid-career triumph to Zuggy? After all, he gave O.W. a nice supporting role for one show (Man In The Shadow) and arranged for him to direct another (Touch Of Evil). The least Orson could do is lend his mellifluous voice to A.Z.’s trailer for The Incredible Shrinking Man. Too bad Universal included only a teaser version on the DVD. The full-length theatrical preview is a real treat, and Welles delivers his narration with gusto. How about these product placements? I hadn’t realized Fire Chief Matches, Superior Paint & Varnish Company, and Authentic Furniture Products had men in the field poised to take orders for this stuff, but I guess there were patrons inspired to buy an extra box of lights after seeing Grant Williams use one of them for a residence. I particularly like that Captain’s Chair they’re touting, but can’t help wondering if some potential customer might have called in a request for an oversized version similar to the one that swallows up poor Scott Carey. Do you suppose any of these gigantic props still exist in a Universal storage warehouse? I read most of them were too flimsy to use for promotions at the time, but who knows? There may be a few left. I'd love to have that giant pencil standing against the wall in my den, but I guess it got ruined during Scott's basement flood.

What a great still of director Jack Arnold and producer Albert Zugsmith being denied access to the Shrinking Man set! Why don’t they do shots like this anymore? Must current movies take themselves so seriously? Zuggy was hanging his hat at Universal during the mid to late fifties, and some of the credits he accumulated were pretty impressive. Written On The Wind, The Tarnished Angels (was Zugsmith the real architect behind that fabled Sirkian touch?), Man In The Shadow (Jeff Chandler as a conflicted western sheriff!), Star In the Dust (John Agar as a conflicted western sheriff!), and TOUCH OF EVIL!! Do we owe Orson Welles’ mid-career triumph to Zuggy? After all, he gave O.W. a nice supporting role for one show (Man In The Shadow) and arranged for him to direct another (Touch Of Evil). The least Orson could do is lend his mellifluous voice to A.Z.’s trailer for The Incredible Shrinking Man. Too bad Universal included only a teaser version on the DVD. The full-length theatrical preview is a real treat, and Welles delivers his narration with gusto. How about these product placements? I hadn’t realized Fire Chief Matches, Superior Paint & Varnish Company, and Authentic Furniture Products had men in the field poised to take orders for this stuff, but I guess there were patrons inspired to buy an extra box of lights after seeing Grant Williams use one of them for a residence. I particularly like that Captain’s Chair they’re touting, but can’t help wondering if some potential customer might have called in a request for an oversized version similar to the one that swallows up poor Scott Carey. Do you suppose any of these gigantic props still exist in a Universal storage warehouse? I read most of them were too flimsy to use for promotions at the time, but who knows? There may be a few left. I'd love to have that giant pencil standing against the wall in my den, but I guess it got ruined during Scott's basement flood.

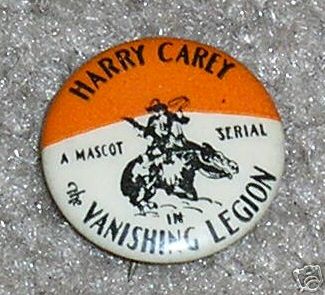

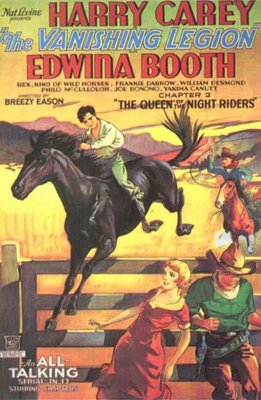

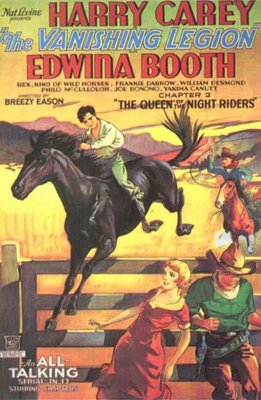

Three Cheers For The Vanishing Legion!There are varying endurance levels when it comes to watching movie serials, usually depending on who produced them. First, there is Republic, the slickest outfit of the lot, and certainly the most efficient in its day. Their serials call to mind precise movements of a fine watch. Stuntwork, music, special effects --- all out of the top drawer. If anything, Republic chapterplays are too polished. Then there is Universal and Columbia. These were not companies dedicated to serials, but they maintained units for manufacturing them, and most were slick affairs. Beneath this level, we have the independent and poverty row output, and this is where we separate Iron Men from those mere dilettantes who but casually watch serials. The stoutest chapterplay completist might boast of having seen all the surviving Mascot serials, a feat requiring epic patience and an appetite for primitivism in movies at least the equal of screening twelve Edison silent shorts end-to-end. I like Mascot serials. I enjoy the sound of horse’s hooves as they race past prehistoric recording equipment. Scuffling noises during fight scenes have a raw and realistic flavor. Sound effects and dialogue are seldom, if ever, dubbed in. You often hear things clearly not meant to be heard. Lines are muffed or altogether forgotten. Actors stand and wait for cues not forthcoming. Sometimes stunts go wrong, or else guys don’t mind crashing open roadsters and having the things flip over on top of them. You always get the feeling there were people killed on these shows and nobody said anything because these were, after all, fringe productions. Nat Levine was the mastermind behind Mascot serials. He shot The Vanishing Legion in 18 days for three thousand dollars a chapter (with the exception of a lavish opening installment at five thousand). If you can get through all twelve, there’s a G.M.B. (Greenbriar Merit Badge) waiting for you in our lobby …

Three Cheers For The Vanishing Legion!There are varying endurance levels when it comes to watching movie serials, usually depending on who produced them. First, there is Republic, the slickest outfit of the lot, and certainly the most efficient in its day. Their serials call to mind precise movements of a fine watch. Stuntwork, music, special effects --- all out of the top drawer. If anything, Republic chapterplays are too polished. Then there is Universal and Columbia. These were not companies dedicated to serials, but they maintained units for manufacturing them, and most were slick affairs. Beneath this level, we have the independent and poverty row output, and this is where we separate Iron Men from those mere dilettantes who but casually watch serials. The stoutest chapterplay completist might boast of having seen all the surviving Mascot serials, a feat requiring epic patience and an appetite for primitivism in movies at least the equal of screening twelve Edison silent shorts end-to-end. I like Mascot serials. I enjoy the sound of horse’s hooves as they race past prehistoric recording equipment. Scuffling noises during fight scenes have a raw and realistic flavor. Sound effects and dialogue are seldom, if ever, dubbed in. You often hear things clearly not meant to be heard. Lines are muffed or altogether forgotten. Actors stand and wait for cues not forthcoming. Sometimes stunts go wrong, or else guys don’t mind crashing open roadsters and having the things flip over on top of them. You always get the feeling there were people killed on these shows and nobody said anything because these were, after all, fringe productions. Nat Levine was the mastermind behind Mascot serials. He shot The Vanishing Legion in 18 days for three thousand dollars a chapter (with the exception of a lavish opening installment at five thousand). If you can get through all twelve, there’s a G.M.B. (Greenbriar Merit Badge) waiting for you in our lobby …

Mascots are the only serials that look as though they were shot in my Grandmother’s backyard. Austere is the operative word here. Harry Carey chases miscreants down streets and through buildings that appear as though they’re still waiting to be wired for electricity. There are no paved roads in this serial, even in the face of its "modern" setting. The town where much of the action takes place is devoid of extras. It’s like everyone either died or cleared out. All the backgrounds have a look of utter desolation. Whatever object or advantage is being fought over could have little monetary or spiritual value against such a bleak void. As with so many serials, you lose track of who’s pursuing who, let alone why. The chase becomes the end in itself, and men exist merely to fall out of windows or be shot at. The alternate Mascot universe never acknowledges ordinary concerns in life. To maintain the pace of a Harry Carey in this show (53 when he made it), you must submit to bullet wounds (Only a scratch, Jimmy), topple off rockbound cliffs (I’ll be all right, Jimmy), and plunge from atop oil derricks (That was a close one, Jimmy!). You can do this sort of thing in the cartoon world of Republic because their chapterplays offered a comforting remove from any sort of recognizable reality, while Mascot serials are all the more unsettling in suggesting, by way of their crudity and obvious lack of studied preparation, that much of this is actually happening to harassed and underpaid cast members. Good God, is that poor Harry being thrown backward down a flight of stairs? Will someone among the threadbare crew drive him to a hospital in the event he really gets hurt? The tension these cliffhangers create is sometimes too real for comfort. You imagine a secret burial on location for some luckless stuntman with a family back in Oshkosh that hasn’t seen him in eighteen years. Who would ever be the wiser?

Nat Levine used faded names and anxious beginners. Harry Carey had been around since Biograph days, but his kind of westerner had gone out with Bill Hart, and despite a recent success with MGM’s Trader Horn, he couldn’t be choosy. Edwina Booth was another Trader Horn veteran, though her inept dialogue delivery here caused even producer Levine to blanch with embarrassment. Twelve-year-old Frankie Darro served as audience identification figure and got one thousand dollars for doing this serial, while Rex, King Of The Wild Horses was coming off a series of silent westerns for Hal Roach. Stunt pioneer Yakima Canutt supervised the riskier action, with much footage purloined from features going back ten years. The Vanishing Legion was enlivened by a mystery villain known as The Voice, so-called because we never glimpse his face, at least not before the unmasking in Chapter Twelve. Pre-stardom Boris Karloff supplies the unseen, but oft-heard, presence throughout, and it’s a credit sometimes omitted from the actor’s filmography. The Voice commands the titular legion. We’re never briefed as to how he imposes his will upon such a large body of men, since they seem to be the only henchmen available to him. Perhaps his sinister intonations are sufficient to assure loyalty. I’m ashamed to say I failed to guess the identity of Mister Big prior to his unmasking (it isn't Boris but another actor who's revealed at the end) --- that may be the result of sheer indifference on my part, as the numbing effect of the glacial narrative over twelve seemingly identical chapters left my head swimming with befuddlement. Based upon the foregoing, you’d not think I’d seek out further Mascot encounters, but something in me longs for The Devil Horse, Mystery Mountain, The Lightning Warrior (Rin-Tin-Tin’s final film!), and all the rest. The only problem, and it’s a major one, is the lack of quality DVD’s available. Insofar as that goes, The Vanishing Legion is a remarkable exception. There is a concern known as The Serial Squadron that offers restorations of many chapterplay favorites. Their transfer of The Vanishing Legion is all digital, and by far the best quality DVD of any Mascot serial I’ve seen. Here's hoping they’ll continue mining these treasures (and you can check out The Serial Squadron’s website HERE).

How To Fill Your Lot On a Friday Night in 1952Just a sampling of the kind of shows that used to pack them in during the early fifties. This one, from November 1952, was typical of combinations that catered to audiences out in the hinterlands. Columbia and Republic used to service a lot of these. Westerns were steady reliables for exhibitors and dependable merchandise for producers. $184,000 in domestic rentals may not seem like a lot for Gene Autry’s Indian Territory, but it was money you could count on, and as long as budgets stayed within prescribed limits, profits were virtually guaranteed. Truly a well-oiled machine, and it ran successfully until television flooded homes with the same stuff for free. Pictures like these died hard in the south, though. In the wake of The Beverly Hillbillies’ success on the home screen, our local Starlite Drive-In booked several nights of Judy Canova oldies in the hopes such relics would sate our presumed appetites for all things country --- and those Columbia Autrys were still kicking around our area right through the mid-sixties. A lot of these westerns have been released on DVD, by the way, and all of them sparkle, having been made from negatives retained by Autry's estate. The ones I've watched have been outstanding.

How To Fill Your Lot On a Friday Night in 1952Just a sampling of the kind of shows that used to pack them in during the early fifties. This one, from November 1952, was typical of combinations that catered to audiences out in the hinterlands. Columbia and Republic used to service a lot of these. Westerns were steady reliables for exhibitors and dependable merchandise for producers. $184,000 in domestic rentals may not seem like a lot for Gene Autry’s Indian Territory, but it was money you could count on, and as long as budgets stayed within prescribed limits, profits were virtually guaranteed. Truly a well-oiled machine, and it ran successfully until television flooded homes with the same stuff for free. Pictures like these died hard in the south, though. In the wake of The Beverly Hillbillies’ success on the home screen, our local Starlite Drive-In booked several nights of Judy Canova oldies in the hopes such relics would sate our presumed appetites for all things country --- and those Columbia Autrys were still kicking around our area right through the mid-sixties. A lot of these westerns have been released on DVD, by the way, and all of them sparkle, having been made from negatives retained by Autry's estate. The ones I've watched have been outstanding.

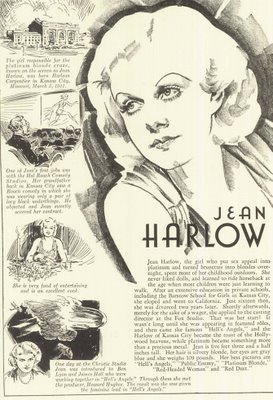

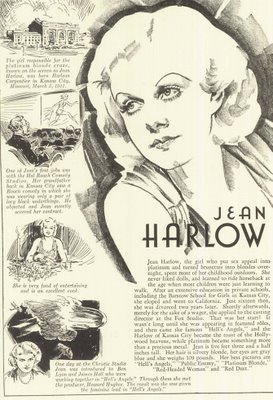

Jean Harlow --- Part TwoCode enforcement signaled the end for Jean Harlow’s established image as surely as it had for Mae West. The character may have been played out in any case, but clearly something had to be done to accommodate the Code and maintain Harlow as a viable ongoing attraction. Hold Your Man was produced and released before the crackdown of mid-1934, but already MGM was softening content, perhaps in response to outcry over Red Dust. This second Gable/Harlow co-starring vehicle was like two wildly disparate movies under a single wobbly umbrella. The first thirty-five or so minutes was bare knuckle pre-code hijinks we could all appreciate (and still do), but that final half doled out excessive punishment to both the actors and their audience, as if to chastise us for having enjoyed what went before. It was a harbinger of worse things to come, not only for Jean Harlow but for a generation of actresses who’d defined themselves in terms of pre-code freedom of expression. Things would never be the same for any of them after this. The Girl From Missouri was the final selection from a menu of titles --- Born To Be Kissed clearly wouldn’t do under the new order, 100% Pure was someone's idea of sarcasm, while Eadie Was A Lady sounded like a Stay Home warning to Harlow’s fan following. August 1934 was the release date, and The Girl From Missouri proudly displayed its PCA seal before the opening credits, assurance for local censors otherwise inclined to apply their own scissors. We’re briefed within minutes as to the rules, and by Harlow herself. I have ideals … I’m a lady … etcetera … a whole new declaration of principles from an actress whose characters had gotten along nicely without them. Harlow was swimming against a new tide, and 1934 audiences had to wonder if they weren’t being sold mislabeled product.

Jean Harlow --- Part TwoCode enforcement signaled the end for Jean Harlow’s established image as surely as it had for Mae West. The character may have been played out in any case, but clearly something had to be done to accommodate the Code and maintain Harlow as a viable ongoing attraction. Hold Your Man was produced and released before the crackdown of mid-1934, but already MGM was softening content, perhaps in response to outcry over Red Dust. This second Gable/Harlow co-starring vehicle was like two wildly disparate movies under a single wobbly umbrella. The first thirty-five or so minutes was bare knuckle pre-code hijinks we could all appreciate (and still do), but that final half doled out excessive punishment to both the actors and their audience, as if to chastise us for having enjoyed what went before. It was a harbinger of worse things to come, not only for Jean Harlow but for a generation of actresses who’d defined themselves in terms of pre-code freedom of expression. Things would never be the same for any of them after this. The Girl From Missouri was the final selection from a menu of titles --- Born To Be Kissed clearly wouldn’t do under the new order, 100% Pure was someone's idea of sarcasm, while Eadie Was A Lady sounded like a Stay Home warning to Harlow’s fan following. August 1934 was the release date, and The Girl From Missouri proudly displayed its PCA seal before the opening credits, assurance for local censors otherwise inclined to apply their own scissors. We’re briefed within minutes as to the rules, and by Harlow herself. I have ideals … I’m a lady … etcetera … a whole new declaration of principles from an actress whose characters had gotten along nicely without them. Harlow was swimming against a new tide, and 1934 audiences had to wonder if they weren’t being sold mislabeled product.

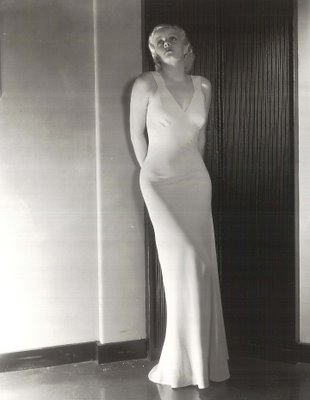

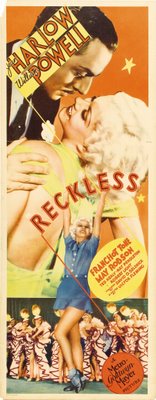

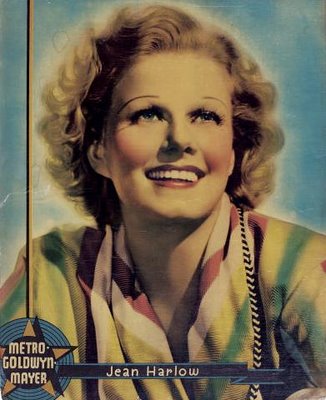

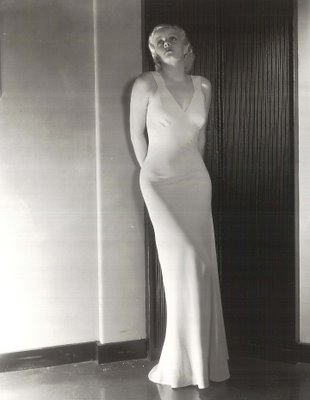

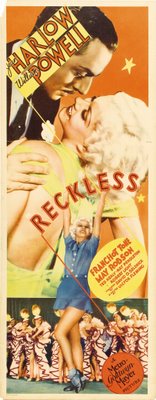

It was a testament to her public’s confidence that Harlow maintained popularity despite the neutering, though a $125,000 loss on Reckless and $63,000 down with Riff-Raff suggested patience might be wearing thin. Metro’s answer was to polish off some rough edges. First, the hair had to change, which was good because it was nearly gone anyway, having been coarsened and ruined over years of mistreatment. The new brownette look went hand in hand with gentler Jean, no longer the barbed wire that wrapped herself around leading men, but an unassuming helpmate, best exemplified by a subdued turn in Wife vs. Secretary. This was 1936, and the adulterous games she’d played onscreen during pre-code years was now a deadly serious business with grave consequences for those who transgressed. Jean’s secretary was a nice girl living at home with Mom and Dad, her gelded suitor a just beginning James Stewart. Whatever sizzle audiences recalled with co-star Clark Gable was lost in the mists of time, as PCA prohibitions against re-issues of forbidden titles kept embargoes firmly in place. Harlow’s compensation was now increased ($3,000 a week), but the suffocating mother was a continuing problem, and the star never girded up sufficient will to fight back. Alcohol became the hidden crutch, though it seldom interfered with work, but what about nagging health problems that plagued her? Impacted wisdom teeth led to a procedure that almost proved fatal, and photographers who’d once tabbed hers the flawless face and figure now applied retouching to both. Romance with urbane William Powell held the promise of eternal commitment, only Bill didn't want to commit, and that resulted in public embarrassment for Jean. This was the world’s most desirable woman, after all.

The image modification seemed to have worked. Profits for the next several were up. Suzy ($498,000), Libeled Lady (1.1 million), and Personal Property ($872,000) promised glad tidings to come. Jean was still young enough to sustain at least another decade of success, unlike older thoroughbreds in Metro stables. As Shearer, Crawford, and Garbo were maturing out, Harlow ascended to first chair among female talent. A forthcoming loan to Fox for their spectacular In Old Chicago promised to team her with man of the hour Tyrone Power. That she would die at this moment was unimaginable, but that’s what happened on June 7, 1937. Her kidneys had been degenerating since that scarlet fever episode in 1926. The crisis point was upon her and nothing could undo years of cumulative damage. A lot of friends and co-workers blamed the crazy mother and her Christian Science-inspired determination to avoid doctors, but Mayo Clinic couldn’t have saved this girl. The shock was all the more palpable because Harlow was genuinely liked among peers, and no one imagined such a dire outcome for her. Death was lingering and painful. The official cause was uremic poisoning --- total organ shutdown and a ghoulish tableau for visitors they’d never get over. She was just 26.

Would Jean Harlow have sustained her popularity into the forties? You ask these questions when pondering the Valentinos, Lombards, Deans, Monroes --- all those who exited early and took promise with them. I suspect Harlow would have aged uncomfortably. She might have been fated to play June Allyson or Gloria DeHaven’s mother, maybe in one of those wartime boosters where she objects to Van Johnson as a suitor or helps put on a camp show with Gene Kelly. Would they have made her do a Lassie? Reunions with Clark Gable would have been unlikely with Lana Turner about, unless it was a character cameo like Mary Astor had with him in Any Number Can Play. Imagine Harlow doing television --- teaming up with Robert Taylor on an episode of The Detectives for old time’s sake. Sometimes a long life isn’t necessarily the best life when it comes to preserving myths. Harlow’s was shattered, then rebuilt, on several occasions after her death. Iconic status was immediately conferred with Metro’s posthumous release of the unfinished Saratoga, which offered the spectacle of both Jean’s final footage and a name-that-double exercise in studio sleight-of-hand. The girl standing in behind glasses, binoculars, and floppy hat was Mary Dees, who died only last year after (nearly) seventy years refusal to discuss Saratoga. Was she haunted by Harlow’s restless spirit? Opportunistic re-issues supplied their own post-mortem. Hell’s Angels was back, but much of her footage was trimmed, while Columbia sustained interest with a Platinum Blonde revival in the late forties. The big noise arrived in the sixties, when writer Irving Schulman offered up a largely fictionalized bio that lit the fuse of many Harlow co-workers who’d loudly declare his perfidy. Even long retired William Powell issued a statement. Two movies were adapted from Shulman’s speculations, but the three million in domestic rentals Paramount realized from its Harlow had to have been a disappointment for them. A few of Jean’s originals made theatrical rounds as well, but Red Dust and Dinner At Eight were mostly there for a handful of repertory bookings and old-timer matinees. The real Harlow comeback would have to wait for TCM and home video, and here was where long buried treasures like Beast Of The City and Libeled Lady reasserted their presence among fans. As for DVD prospects, Red-Headed Woman is slated for next month, and word is a Harlow box will follow.

Photo CaptionsJean Harlow in Platinum BlondeJean's Picture Personalities ProfileMGM Publicity PortraitWith Wallace Beery in Dinner At EightPoster Art for The Girl From MissouriReckless InsertJumbo Lobby Card from Libeled LadyMGM Publicity PortraitWith William Powell in RecklessWith husband Harold Rosson, unrepentant gigolo step-father Marino Bello, and her mother.Publicity for Harlow's new Brownette hair-styleFilming Saratoga with Lionel Barrymore, Walter Pidgeon, and director Jack Conway --- this may have been her last day on that set before she died.

Captains Courageous and Freddie's Liberty No-Show

Captains Courageous and Freddie's Liberty No-Show Jason Apuzzo over at LIBERTAS recommended Captains Courageous a week or so ago and I decided to take another look at it. You go for years ignoring pictures like this and they’re always a surprise upon revisiting. C.C. asserted itself often enough in documentaries where that clip of Spencer Tracy singing with an accent played seemingly on a loop. For a lot of people, it summed up the meaning of a classic movie moment. Captains Courageous has long been recognized as Tracy’s picture, but for me, the billing tells the truer story. This is Freddie Bartholomew’s show, and he’s fantastic throughout. I’d forgotten how effective kid actors could be in those days. What a shame Freddie had to grow up, and how unfortunate that MGM dropped him so callously after typecasting the child into a rut during his prime earning years. Audiences react differently to bratty kids in movies. It’s enough for most of us to wait for the character to receive his comeuppance and become a better boy. Sometimes if the youngster is particularly revolting like Jackie Searle or David Holt, we long for him to be punished straightaway, if not killed off altogether. Bartholomew walks that fine line of viewer tolerance, but never crosses it. I was happy to see him fall off the ocean liner, but I didn’t want to see him drown. Is this what separates great child actors from merely competent ones? For such a fine performer, Freddie got a bum deal in American movies. His British propriety looked sissified to many, and some of the roles seemed old-fashioned even then (Little Lord Fauntleroy). I’ll bet there were gangs of boys waiting around stage doors to beat him up after personal appearances. His was the persistent voice of reason that kept scrappier youth like Mickey Rooney and Jackie Cooper out of harm’s way. Too often his character came across as a prig and a party pooper, but more about Freddie later …

Jason Apuzzo over at LIBERTAS recommended Captains Courageous a week or so ago and I decided to take another look at it. You go for years ignoring pictures like this and they’re always a surprise upon revisiting. C.C. asserted itself often enough in documentaries where that clip of Spencer Tracy singing with an accent played seemingly on a loop. For a lot of people, it summed up the meaning of a classic movie moment. Captains Courageous has long been recognized as Tracy’s picture, but for me, the billing tells the truer story. This is Freddie Bartholomew’s show, and he’s fantastic throughout. I’d forgotten how effective kid actors could be in those days. What a shame Freddie had to grow up, and how unfortunate that MGM dropped him so callously after typecasting the child into a rut during his prime earning years. Audiences react differently to bratty kids in movies. It’s enough for most of us to wait for the character to receive his comeuppance and become a better boy. Sometimes if the youngster is particularly revolting like Jackie Searle or David Holt, we long for him to be punished straightaway, if not killed off altogether. Bartholomew walks that fine line of viewer tolerance, but never crosses it. I was happy to see him fall off the ocean liner, but I didn’t want to see him drown. Is this what separates great child actors from merely competent ones? For such a fine performer, Freddie got a bum deal in American movies. His British propriety looked sissified to many, and some of the roles seemed old-fashioned even then (Little Lord Fauntleroy). I’ll bet there were gangs of boys waiting around stage doors to beat him up after personal appearances. His was the persistent voice of reason that kept scrappier youth like Mickey Rooney and Jackie Cooper out of harm’s way. Too often his character came across as a prig and a party pooper, but more about Freddie later …

Accents are a curse upon otherwise fine actors. I cringe whenever John Barrymore or Laurence Olivier enter a room and make with the foreign inflections, because you know you’re stuck with it for the run of the feature, and most of the time, that’s agony. Even regional dialects culled from within our own shores can play like broken air-conditioners in a suffocating room. Of the countless southerners I’ve encountered over a life lived in Dixie environs, none have addressed me as Orson Welles does other cast members in The Long, Hot Summer. My query, then, to MGM producers --- Why must Spencer Tracy be Portuguese at all? They’re not shipping out of Portugal in Captains Courageous, and I dare say, fishermen from that country would almost certainly be loathe to go about speaking like Chico Marx. Joan Crawford immediately drew that comparison when she first saw Tracy in costume, and it’s impossible to watch Captains Courageous without making the unfortunate connection. I keep thinking of how powerful Spence could have been if they’d just let him use his natural voice (and that’s director Victor Fleming with the actor on the set of C.C.). As it is, I actually prefer Freddie’s scenes with Lionel Barrymore; indeed this would be one of that actor’s final roles standing up, as within a year he’d be confined to either crutches or a wheelchair. Tracy does become more palatable as the story progresses --- the real Oscar-worthiness of his performance lay in Spence’s ability to overcome the disadvantages inherent in the role (and that ringlet-curled hair!). It may have been the engraver’s idea of a joke when they inscribed the name Dick Tracy on the initial Best Actor award he was given for Captains Courageous, but the more unwelcome gesture came when MGM chief Louis B. Mayer stepped to the podium that night to pay his own acid tribute --- Tracy is a fine actor, but he is most important because he understands why it is necessary to take orders from the front office. Was this a public admonition for the sometimes drink-addled Tracy, whose disappearances from the set had caused production delays and overruns? Captains Courageous actually had a negative cost of 1.6 million, which was considerable money for 1937 (but surprisingly, the same year's A Day At The Races cost even more). Domestic rentals were 1.6 million, with foreign at 1.4. Final profit for the picture was $355,000.

Accents are a curse upon otherwise fine actors. I cringe whenever John Barrymore or Laurence Olivier enter a room and make with the foreign inflections, because you know you’re stuck with it for the run of the feature, and most of the time, that’s agony. Even regional dialects culled from within our own shores can play like broken air-conditioners in a suffocating room. Of the countless southerners I’ve encountered over a life lived in Dixie environs, none have addressed me as Orson Welles does other cast members in The Long, Hot Summer. My query, then, to MGM producers --- Why must Spencer Tracy be Portuguese at all? They’re not shipping out of Portugal in Captains Courageous, and I dare say, fishermen from that country would almost certainly be loathe to go about speaking like Chico Marx. Joan Crawford immediately drew that comparison when she first saw Tracy in costume, and it’s impossible to watch Captains Courageous without making the unfortunate connection. I keep thinking of how powerful Spence could have been if they’d just let him use his natural voice (and that’s director Victor Fleming with the actor on the set of C.C.). As it is, I actually prefer Freddie’s scenes with Lionel Barrymore; indeed this would be one of that actor’s final roles standing up, as within a year he’d be confined to either crutches or a wheelchair. Tracy does become more palatable as the story progresses --- the real Oscar-worthiness of his performance lay in Spence’s ability to overcome the disadvantages inherent in the role (and that ringlet-curled hair!). It may have been the engraver’s idea of a joke when they inscribed the name Dick Tracy on the initial Best Actor award he was given for Captains Courageous, but the more unwelcome gesture came when MGM chief Louis B. Mayer stepped to the podium that night to pay his own acid tribute --- Tracy is a fine actor, but he is most important because he understands why it is necessary to take orders from the front office. Was this a public admonition for the sometimes drink-addled Tracy, whose disappearances from the set had caused production delays and overruns? Captains Courageous actually had a negative cost of 1.6 million, which was considerable money for 1937 (but surprisingly, the same year's A Day At The Races cost even more). Domestic rentals were 1.6 million, with foreign at 1.4. Final profit for the picture was $355,000.