Region 2 Round-Up --- Part OneRegion 2 can be a rich vein in which to mine for DVD rarities. Sometitles available across the pond may never see light of day here. It’s true our hardware won’t play them, but there’s (easy) ways around that, and effort of retrofitting your player (or purchasing a so-called region free model) is rewarded ten-fold by features like A Distant Trumpet, and 1962’s The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse , along with many others which continue to surface in countries like France, Germany, and the UK. Legendes Of Cinema and Collection Grands Classiques Du Cinema Americain are French umbrellas for DVD groups dedicated to auteur directors. We might wait years to get some of these released stateside. I’ve enjoyed eight this past week, and have found quality consistent with what’s released here. The PAL conversion resulting in a slight speed-up is something I’ve not noticed, but I can’t hear dog whistles either, so maybe there’s advantage after all in growing old and deaf. My first submersion was Fritz Lang’s Moonfleet, released in 1955 and largely ignored since. Maltin’s guide calls this one tepid, but I didn’t find it so. A welcome antidote to kid-friendly pirate movies, especially those which share a child protagonist, Moonfleet is refreshingly adult and way more sophisticated than earlier Disney and MGM forays into similar waters (Treasure Island being most similar). Lang didn’t have luxury of prep time he’d enjoyed in Germany, but Metro expertise in staging period pageantry is still intact, though for perhaps a last time with Moonfleet (did they do another serious in-house costume picture after this?). It’s absence from the MGM Children’s Matinee inventory during the late sixties/early seventies reflects an integrity and refusal to soften material for juvenile sensibilities (though 1955 kids surely enjoyed, and were probably flattered by, Moonfleet’s mature approach). Atmosphere is well maintained throughout. Graveyard scenes are creepy and onscreen deaths are at times grisly. George Sanders’ presence reassures that we aren’t watching a kiddie show, despite moments when his disinterest was such that I thought GS might actually nod off on camera. I see where Moonfleet lost nearly a million dollars, no disgrace as other worthy Metro pictures of that year performed even worse (The Cobweb and It’s Always Fair Weather, for instance). The Stewart Granger actioners were losing ground just as Robert Taylor’s costumers hit the rocks. Both Moonfleet and The Adventures Of Quentin Durward ($908,000 lost) put paid to future MGM ventures along these lines. Were audiences as content to sit home watching Sir Francis Drake and Richard Greene’s Robin Hood on their televisions?

Region 2 Round-Up --- Part OneRegion 2 can be a rich vein in which to mine for DVD rarities. Sometitles available across the pond may never see light of day here. It’s true our hardware won’t play them, but there’s (easy) ways around that, and effort of retrofitting your player (or purchasing a so-called region free model) is rewarded ten-fold by features like A Distant Trumpet, and 1962’s The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse , along with many others which continue to surface in countries like France, Germany, and the UK. Legendes Of Cinema and Collection Grands Classiques Du Cinema Americain are French umbrellas for DVD groups dedicated to auteur directors. We might wait years to get some of these released stateside. I’ve enjoyed eight this past week, and have found quality consistent with what’s released here. The PAL conversion resulting in a slight speed-up is something I’ve not noticed, but I can’t hear dog whistles either, so maybe there’s advantage after all in growing old and deaf. My first submersion was Fritz Lang’s Moonfleet, released in 1955 and largely ignored since. Maltin’s guide calls this one tepid, but I didn’t find it so. A welcome antidote to kid-friendly pirate movies, especially those which share a child protagonist, Moonfleet is refreshingly adult and way more sophisticated than earlier Disney and MGM forays into similar waters (Treasure Island being most similar). Lang didn’t have luxury of prep time he’d enjoyed in Germany, but Metro expertise in staging period pageantry is still intact, though for perhaps a last time with Moonfleet (did they do another serious in-house costume picture after this?). It’s absence from the MGM Children’s Matinee inventory during the late sixties/early seventies reflects an integrity and refusal to soften material for juvenile sensibilities (though 1955 kids surely enjoyed, and were probably flattered by, Moonfleet’s mature approach). Atmosphere is well maintained throughout. Graveyard scenes are creepy and onscreen deaths are at times grisly. George Sanders’ presence reassures that we aren’t watching a kiddie show, despite moments when his disinterest was such that I thought GS might actually nod off on camera. I see where Moonfleet lost nearly a million dollars, no disgrace as other worthy Metro pictures of that year performed even worse (The Cobweb and It’s Always Fair Weather, for instance). The Stewart Granger actioners were losing ground just as Robert Taylor’s costumers hit the rocks. Both Moonfleet and The Adventures Of Quentin Durward ($908,000 lost) put paid to future MGM ventures along these lines. Were audiences as content to sit home watching Sir Francis Drake and Richard Greene’s Robin Hood on their televisions?

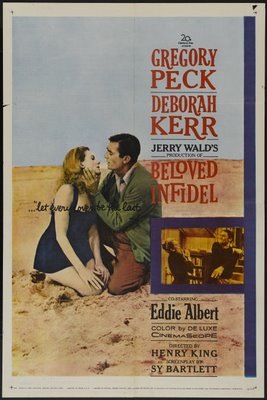

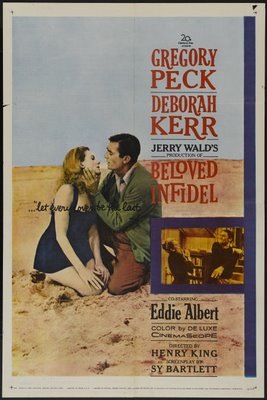

Gregory Peck plays some excruciating drunk scenes in 20th Fox’s Beloved Infidel, a supposedly fact-based story of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald’s affair with Hollywood columnist Sheilah Graham. The movie was produced by post-Peyton Place Jerry Wald, so you’d expect more of a cutting edge, but director Henry King (who applauded the Code and its strict application) lends an old-style formality that no doubt contributed to a $1.5 million bath his studio took on this picture. Hollywood decadence is suggested by extras chasing each other around a sound stage pool, and never was Tijuana depicted so clumsily as here (WB’s Viva Buddy cartoon from 1934 seems near-documentary in comparison). Eddie Albert is again the alcoholic’s best friend and severest critic (must it always be Eddie in such parts?). Greg crawls in and out of his bottle like a serial hero in quest of the treasure map, while Deborah Kerr forgives and waits patiently for a next walloping. Beloved Infidel is what they once called "mature entertainment", but for my money, The Colossus Of New York offers more nourishing food for thought. Best parts were shot around the Fox lot and on sound stages, lending Beloved Infidel what little verisimilitude it has. Though specific studios aren’t identified, at least we don’t resort to signs above gates reading Mammoth, Monarch, or Miracle Pictures, as so many filmland depictions invariably do. They’re shooting In Old Chicago during one sequence, but the haughty and pampered leading lady gets a (fictional) name other than Alice Faye. It’s doubtful any but the most sharp-eyed observers in 1959 would have noticed origin of that scene being filmed, since In Old Chicago had been out of theatrical circulation for years, and was otherwise a fixture (among hundreds of other Fox oldies) on late night television. Latter-day viewers will be alarmed to see Gregory Peck drinking from a smuggled quart bottle of gin on a passenger flight (and no seat belt either!), while Deborah Kerr occupies what appears to be the plane's lone sleeping berth (at least it’s an upper!). The only thing lacking is one of those observation platforms such as Bill Fields enjoyed in Never Give A Sucker An Even Break. Welcome character support Herbert Rudley graduates from The Black Sleep to play Peck’s producer boss. The two were old friends from starting-out days and Greg threw Herb work both here and in 1958’s The Bravados. Movies about drunks are frustrating for predictable seesaw characters invariably ride. The only question is whether he/she will live or die in a final reel, but this being Fitzgerald’s story, even that element of suspense is vitiated by our knowledge he’ll surely collapse before that finish.

Gregory Peck plays some excruciating drunk scenes in 20th Fox’s Beloved Infidel, a supposedly fact-based story of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald’s affair with Hollywood columnist Sheilah Graham. The movie was produced by post-Peyton Place Jerry Wald, so you’d expect more of a cutting edge, but director Henry King (who applauded the Code and its strict application) lends an old-style formality that no doubt contributed to a $1.5 million bath his studio took on this picture. Hollywood decadence is suggested by extras chasing each other around a sound stage pool, and never was Tijuana depicted so clumsily as here (WB’s Viva Buddy cartoon from 1934 seems near-documentary in comparison). Eddie Albert is again the alcoholic’s best friend and severest critic (must it always be Eddie in such parts?). Greg crawls in and out of his bottle like a serial hero in quest of the treasure map, while Deborah Kerr forgives and waits patiently for a next walloping. Beloved Infidel is what they once called "mature entertainment", but for my money, The Colossus Of New York offers more nourishing food for thought. Best parts were shot around the Fox lot and on sound stages, lending Beloved Infidel what little verisimilitude it has. Though specific studios aren’t identified, at least we don’t resort to signs above gates reading Mammoth, Monarch, or Miracle Pictures, as so many filmland depictions invariably do. They’re shooting In Old Chicago during one sequence, but the haughty and pampered leading lady gets a (fictional) name other than Alice Faye. It’s doubtful any but the most sharp-eyed observers in 1959 would have noticed origin of that scene being filmed, since In Old Chicago had been out of theatrical circulation for years, and was otherwise a fixture (among hundreds of other Fox oldies) on late night television. Latter-day viewers will be alarmed to see Gregory Peck drinking from a smuggled quart bottle of gin on a passenger flight (and no seat belt either!), while Deborah Kerr occupies what appears to be the plane's lone sleeping berth (at least it’s an upper!). The only thing lacking is one of those observation platforms such as Bill Fields enjoyed in Never Give A Sucker An Even Break. Welcome character support Herbert Rudley graduates from The Black Sleep to play Peck’s producer boss. The two were old friends from starting-out days and Greg threw Herb work both here and in 1958’s The Bravados. Movies about drunks are frustrating for predictable seesaw characters invariably ride. The only question is whether he/she will live or die in a final reel, but this being Fitzgerald’s story, even that element of suspense is vitiated by our knowledge he’ll surely collapse before that finish.

Curse Of The Fly was, for me, the most unnerving of that waning series. I didn’t even bother going to see it in 1965, but should have. The poster implies more (literal) flies in experimental ointments, but thankfully, there’s none of that. Credibility might well have been strained to breaking points had yet another housefly gotten into the teleportation (is that what it was?) chamber just before switches were turned. Besides, that last Fly head was so oversized as to be unwieldy, Fox no doubt operating on theories that the bigger the appendage, the scarier its effect. In fact, the opposite was true. Curse Of The Fly’s mid-sixties arrival must have surprised fans. You wouldn’t have thought they’d do another one of these after a six-year lapse. This time out, actions have real consequence for the accursed Delambres, as failed experiments over an indeterminate period have left any number of mutated unfortunates imprisoned among convenient cells within the family compound. Fleeting glimpses of these provide harrowing moments in the show, and notions that former wives are stored up along with the rest lends queasy reality that’s a real departure from lazy and conventional shocks delivered by previous Return Of The Fly. Characters emerge from aforementioned chamber with nasty radiation burns (as if portly and drink-addled Brian Donlevy needed yet another handicap!), while mutants, leads, and whatnot are transported willy-nilly from one continent to another without so much as a by-your-leave. I was actually confused as to who went where by the end, though I suspect a few luckless individuals were left in a kind of phantom zone transit similar to the one that entrapped General Zod and his compatriots in the Superman features. Donlevy contributes one of those I’m giving it my best even if it’s unworthy of me performances that were hallmarks of so many leading men reduced to low-budget sci-fi pics in the fifties. A pity he couldn’t live long enough to realize what a devoted following his Quatermass and similar experiments would have among middle-agers who grew up with them. Curse Of the Fly was made for a remarkably frugal $108,000. How could you help but get a profit having spent so little as that? --- and yet there was only $145,000 in domestic rentals and $115,000 foreign. After prints and advertising, the picture ended up dead even, one of the few titles on Fox ledgers that fell neither way.

Curse Of The Fly was, for me, the most unnerving of that waning series. I didn’t even bother going to see it in 1965, but should have. The poster implies more (literal) flies in experimental ointments, but thankfully, there’s none of that. Credibility might well have been strained to breaking points had yet another housefly gotten into the teleportation (is that what it was?) chamber just before switches were turned. Besides, that last Fly head was so oversized as to be unwieldy, Fox no doubt operating on theories that the bigger the appendage, the scarier its effect. In fact, the opposite was true. Curse Of The Fly’s mid-sixties arrival must have surprised fans. You wouldn’t have thought they’d do another one of these after a six-year lapse. This time out, actions have real consequence for the accursed Delambres, as failed experiments over an indeterminate period have left any number of mutated unfortunates imprisoned among convenient cells within the family compound. Fleeting glimpses of these provide harrowing moments in the show, and notions that former wives are stored up along with the rest lends queasy reality that’s a real departure from lazy and conventional shocks delivered by previous Return Of The Fly. Characters emerge from aforementioned chamber with nasty radiation burns (as if portly and drink-addled Brian Donlevy needed yet another handicap!), while mutants, leads, and whatnot are transported willy-nilly from one continent to another without so much as a by-your-leave. I was actually confused as to who went where by the end, though I suspect a few luckless individuals were left in a kind of phantom zone transit similar to the one that entrapped General Zod and his compatriots in the Superman features. Donlevy contributes one of those I’m giving it my best even if it’s unworthy of me performances that were hallmarks of so many leading men reduced to low-budget sci-fi pics in the fifties. A pity he couldn’t live long enough to realize what a devoted following his Quatermass and similar experiments would have among middle-agers who grew up with them. Curse Of the Fly was made for a remarkably frugal $108,000. How could you help but get a profit having spent so little as that? --- and yet there was only $145,000 in domestic rentals and $115,000 foreign. After prints and advertising, the picture ended up dead even, one of the few titles on Fox ledgers that fell neither way.

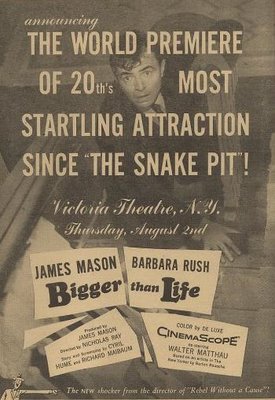

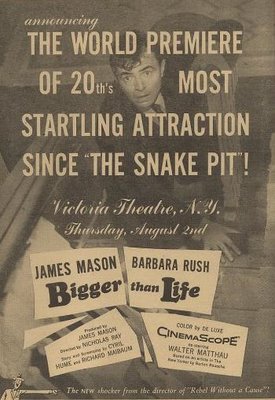

Monsters From The Id seem to have been turned loose in a number of family men during those alleged "repressed" fifties. Walter Pidgeon in Forbidden Planet is an extreme example, but James Mason gets Bigger Than Life by a mere overdose of Cortisone, which I assume they don’t hand out so freely (at least in pill form) anymore, judging by his psychotic reaction here. Initial euphoria leads Mason to imagine there’s an escape from middle-class obligation and petty compromises, and tragedy comes in the realization there’s no way out. Academics have performed tribal dances around this show for decades (or at least since auteurism gained currency), as it seems to confirm all their assumptions about a bleak post-war social landscape. Bigger Than Life is bound to have depressed a lot of 1956 drive-inners unprepared for such an unsparing dissection of their workaday traps. Word-of-mouth was surely ruinous. The fact it would lose $875,000 for Fox might have been something they saw coming from first previews. I wonder if 20th even realized prestige for having made it. Unlike phony-baloney preachments of their late-forties social ventures, Bigger Than Life went right to the bone, and kept slicing. You could dismiss it as melodrama, but only if you’re not paying close attention. Kids ignorant of adult ramifications would have been horrified by one of their number suffering relentless parental abuse. I was so bothered upon seeing it on NBC’s Monday Night At The Movies in 1963 as to avoid further contact for what ... forty-four years? Just this week, I finally steeled myself to watch Bigger Than Life again. Never was the desperation of family responsibility so chillingly enacted. Show this to your teenagers if you want them to stay single. Recent shows like American Beauty and Election undoubtedly drew inspiration from director Nicholas Ray. It’s a miracle Bigger Than Life even got made. Producer-star James Mason must have called in a lot of markers. Why not put Robert Wagner on a horse and have at least some chance of getting your investment back? In fact, that’s exactly what Fox and Nicholas Ray would do the following year with The True Story Of Jesse James.

Monsters From The Id seem to have been turned loose in a number of family men during those alleged "repressed" fifties. Walter Pidgeon in Forbidden Planet is an extreme example, but James Mason gets Bigger Than Life by a mere overdose of Cortisone, which I assume they don’t hand out so freely (at least in pill form) anymore, judging by his psychotic reaction here. Initial euphoria leads Mason to imagine there’s an escape from middle-class obligation and petty compromises, and tragedy comes in the realization there’s no way out. Academics have performed tribal dances around this show for decades (or at least since auteurism gained currency), as it seems to confirm all their assumptions about a bleak post-war social landscape. Bigger Than Life is bound to have depressed a lot of 1956 drive-inners unprepared for such an unsparing dissection of their workaday traps. Word-of-mouth was surely ruinous. The fact it would lose $875,000 for Fox might have been something they saw coming from first previews. I wonder if 20th even realized prestige for having made it. Unlike phony-baloney preachments of their late-forties social ventures, Bigger Than Life went right to the bone, and kept slicing. You could dismiss it as melodrama, but only if you’re not paying close attention. Kids ignorant of adult ramifications would have been horrified by one of their number suffering relentless parental abuse. I was so bothered upon seeing it on NBC’s Monday Night At The Movies in 1963 as to avoid further contact for what ... forty-four years? Just this week, I finally steeled myself to watch Bigger Than Life again. Never was the desperation of family responsibility so chillingly enacted. Show this to your teenagers if you want them to stay single. Recent shows like American Beauty and Election undoubtedly drew inspiration from director Nicholas Ray. It’s a miracle Bigger Than Life even got made. Producer-star James Mason must have called in a lot of markers. Why not put Robert Wagner on a horse and have at least some chance of getting your investment back? In fact, that’s exactly what Fox and Nicholas Ray would do the following year with The True Story Of Jesse James.

Would The Circus Ever Come Back To Town?

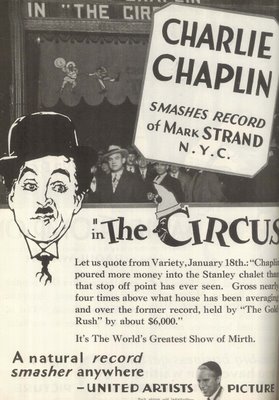

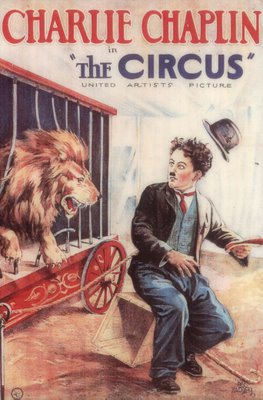

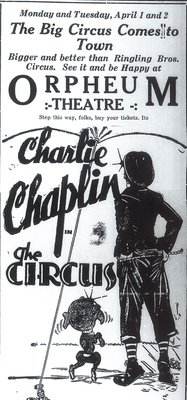

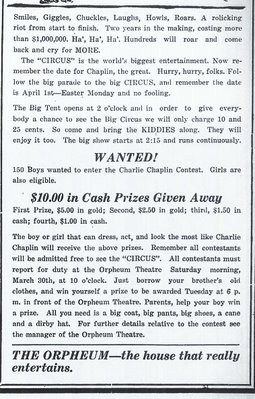

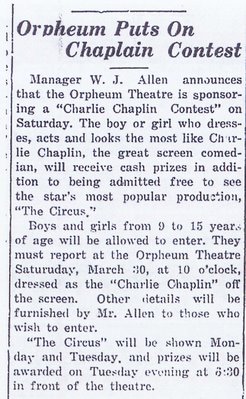

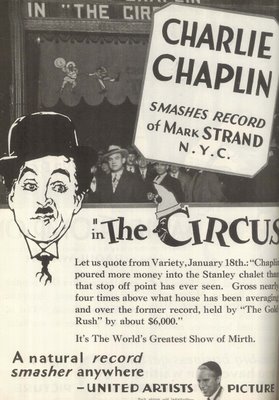

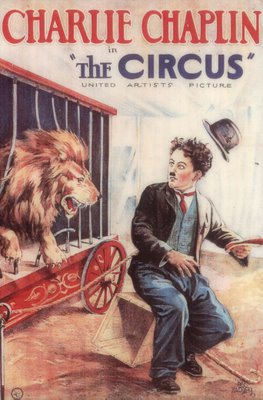

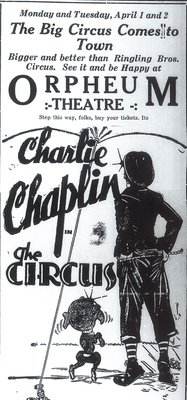

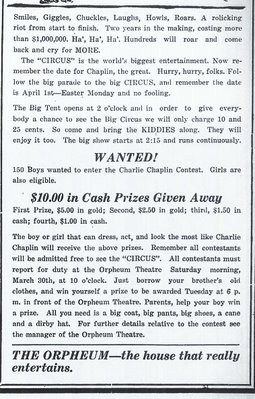

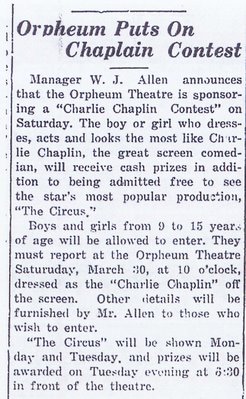

Would The Circus Ever Come Back To Town? I’d have to assume there weren’t a lot of gold coins in circulation around my hometime back in April 1929, so the fact they were given away as prizes in a Charlie Chaplin Look-A-Like contest at the Orpheum Theatre is all the more astonishing in hindsight. Hard times for our community arrived long before the depression. I’ll bet people ate grass. Life was not unlike what we saw in To Kill A Mockingbird, except few houses were as nice as the one Atticus Finch occupied. The Circus had opened in January 1928 at the Mark Strand in New York. We got it fifteen months later. The Orpheum’s newspaper ad was the largest one submitted in all of that year (so much so I’ve broken it into two parts for illustration here), surpassing even their announcement of sound on disc in December 1929. Manager W.J. Allen would eventually take over the Orpheum (in 1941) and give it his name, operating the same clear through to a fire that would gut the premises in 1962. Boy and girl contestants from nine to fifteen were invited to don Tramp outfits and report to the theatre on Saturday morning, March 30. I’m betting a lot of them merely wore their school clothes for all the likely difference between those and Charlie’s raggedy screen attire. Parents would no doubt have lent assist toward scoring five dollars in gold (first prize), with another $5.00 for runners-up. Craven grown-up imposters might well don Chaplinesque garb themselves to get in on money like this, despite the stated age limit. I did ask one of our venerable locals (now in his nineties) if by chance he recalled the contest, but no luck.

I’d have to assume there weren’t a lot of gold coins in circulation around my hometime back in April 1929, so the fact they were given away as prizes in a Charlie Chaplin Look-A-Like contest at the Orpheum Theatre is all the more astonishing in hindsight. Hard times for our community arrived long before the depression. I’ll bet people ate grass. Life was not unlike what we saw in To Kill A Mockingbird, except few houses were as nice as the one Atticus Finch occupied. The Circus had opened in January 1928 at the Mark Strand in New York. We got it fifteen months later. The Orpheum’s newspaper ad was the largest one submitted in all of that year (so much so I’ve broken it into two parts for illustration here), surpassing even their announcement of sound on disc in December 1929. Manager W.J. Allen would eventually take over the Orpheum (in 1941) and give it his name, operating the same clear through to a fire that would gut the premises in 1962. Boy and girl contestants from nine to fifteen were invited to don Tramp outfits and report to the theatre on Saturday morning, March 30. I’m betting a lot of them merely wore their school clothes for all the likely difference between those and Charlie’s raggedy screen attire. Parents would no doubt have lent assist toward scoring five dollars in gold (first prize), with another $5.00 for runners-up. Craven grown-up imposters might well don Chaplinesque garb themselves to get in on money like this, despite the stated age limit. I did ask one of our venerable locals (now in his nineties) if by chance he recalled the contest, but no luck.

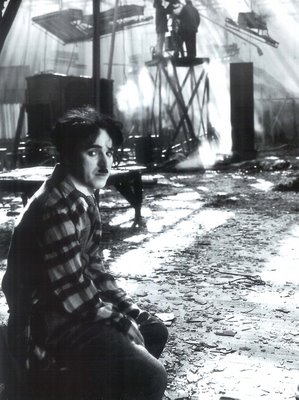

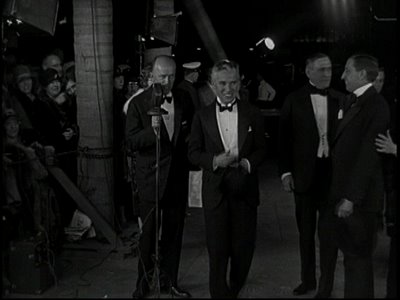

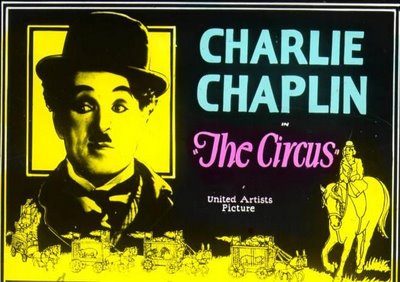

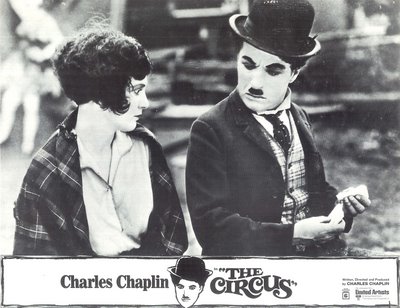

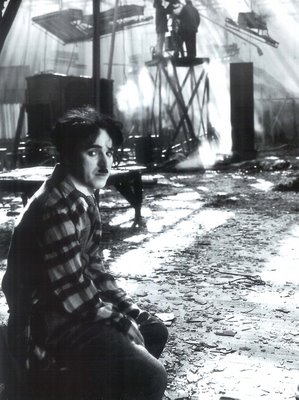

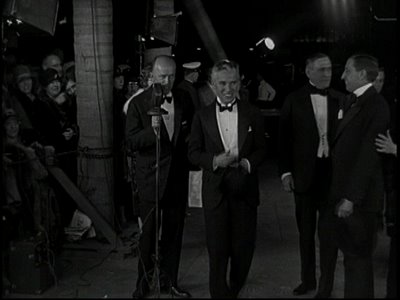

That Orpheum ad refers to The Circus costing over $1,000,000, and indeed, that isn’t puffery, for the final tab rose to $1.1 million, thanks to cost overruns brought on by a series of disasters that plagued production from start to finish. Chaplin's big-top tent blew away in a gale, then all the sets burned down in a cataclysm that nearly laid waste to the studio itself. This shot of Charlie amidst the rubble was a photo-op he could have done without, but I like the way he’s incorporated even that disaster into another visual chapter of individual myth-making. The nervous breakdown that followed put him on the ropes for another eight months of delayed production, and Lita Grey’s bird-dog legal team had designs on the unfinished negative (as with The Kid and Mildred Harris, Chaplin was obliged to hide it). The Jazz Singer had meantime opened in the Autumn of 1927, and holdovers for that one (as shown below) actually delayed The Circus openings in some houses. Latter-day legend abounds as to a critical and commercial chill, but Charlie’s new show was boffo, if not quite in The Gold Rush’s league (here he is at the Hollywood premiere). $1.9 million in domestic rentals led to a worldwide $3.008 total (against $2.2 domestic and $4.3 worldwide for The Gold Rush). For all that success, there were still a few exhibitor sourpusses, though it’s hard to imagine B.R. Parsons of the State Theatre in Springfield, Minnesota was watching the same movie as the rest of us when he wrote, If this is Chaplin’s best, I would hate to take a look at his worst. This is absolutely a lemon, the poorest thing I have seen in many a month. If you buy it for thirty-five dollars and sell it to the public for thirty-five cents, it might please. But don’t play it as a big special because it isn’t there. With support like this in exhibition, is it any wonder Charlie’s hair turned white by the end of shooting?

That Orpheum ad refers to The Circus costing over $1,000,000, and indeed, that isn’t puffery, for the final tab rose to $1.1 million, thanks to cost overruns brought on by a series of disasters that plagued production from start to finish. Chaplin's big-top tent blew away in a gale, then all the sets burned down in a cataclysm that nearly laid waste to the studio itself. This shot of Charlie amidst the rubble was a photo-op he could have done without, but I like the way he’s incorporated even that disaster into another visual chapter of individual myth-making. The nervous breakdown that followed put him on the ropes for another eight months of delayed production, and Lita Grey’s bird-dog legal team had designs on the unfinished negative (as with The Kid and Mildred Harris, Chaplin was obliged to hide it). The Jazz Singer had meantime opened in the Autumn of 1927, and holdovers for that one (as shown below) actually delayed The Circus openings in some houses. Latter-day legend abounds as to a critical and commercial chill, but Charlie’s new show was boffo, if not quite in The Gold Rush’s league (here he is at the Hollywood premiere). $1.9 million in domestic rentals led to a worldwide $3.008 total (against $2.2 domestic and $4.3 worldwide for The Gold Rush). For all that success, there were still a few exhibitor sourpusses, though it’s hard to imagine B.R. Parsons of the State Theatre in Springfield, Minnesota was watching the same movie as the rest of us when he wrote, If this is Chaplin’s best, I would hate to take a look at his worst. This is absolutely a lemon, the poorest thing I have seen in many a month. If you buy it for thirty-five dollars and sell it to the public for thirty-five cents, it might please. But don’t play it as a big special because it isn’t there. With support like this in exhibition, is it any wonder Charlie’s hair turned white by the end of shooting?

Circus sightings were rare in years to come. Chaplin had seen fit to bury it, owing no doubt to bad associations he’d maintained. Since C.C. owned the negative, United Artists could not exhibit the film without his consent. There were re-issues of The Gold Rush in 1942 and City Lights in 1950. Both did well. In the wake of Charlie’s re-entry troubles after the completion of Limelight, his films went into US moratorium. Collectors and Chaplin students walked black market by-ways in an effort to fill gaps on comedies they hadn't seen. William K. Everson maintained The Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society throughout the fifties, which was a private screening club made up of NYC film buffs. Bill prided himself on presenting titles otherwise inaccessible. The Circus was forbidden fruit of a particularly exotic flavor. Everson played it to the group, first in 1953, again in 1957, an excerpt in 1959, and finally complete again in 1964. His program notes from each of these shows are fascinating. The initial print was described as very much scratched and chopped up --- defects consist primarily of the clipping short of certain scenes, and the total elimination of certain shots --- it was, in fact, missing nearly a reel of footage. The one he presented in 1957 was taken from the same bootlegged negative, but was at least in better physical condition. In those days, it was a thrill seeing anything on The Circus. Revival theatres couldn’t get bookings, as Chaplin had no interest in making it available. Everson’s group, with their indifferent (and constantly changing) venues, straight-backed chairs, and chattering 16mm projectors was the only way you could view The Circus in New York for all those decades before Chaplin's authorized reissue finally came in 1969.

Circus sightings were rare in years to come. Chaplin had seen fit to bury it, owing no doubt to bad associations he’d maintained. Since C.C. owned the negative, United Artists could not exhibit the film without his consent. There were re-issues of The Gold Rush in 1942 and City Lights in 1950. Both did well. In the wake of Charlie’s re-entry troubles after the completion of Limelight, his films went into US moratorium. Collectors and Chaplin students walked black market by-ways in an effort to fill gaps on comedies they hadn't seen. William K. Everson maintained The Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society throughout the fifties, which was a private screening club made up of NYC film buffs. Bill prided himself on presenting titles otherwise inaccessible. The Circus was forbidden fruit of a particularly exotic flavor. Everson played it to the group, first in 1953, again in 1957, an excerpt in 1959, and finally complete again in 1964. His program notes from each of these shows are fascinating. The initial print was described as very much scratched and chopped up --- defects consist primarily of the clipping short of certain scenes, and the total elimination of certain shots --- it was, in fact, missing nearly a reel of footage. The one he presented in 1957 was taken from the same bootlegged negative, but was at least in better physical condition. In those days, it was a thrill seeing anything on The Circus. Revival theatres couldn’t get bookings, as Chaplin had no interest in making it available. Everson’s group, with their indifferent (and constantly changing) venues, straight-backed chairs, and chattering 16mm projectors was the only way you could view The Circus in New York for all those decades before Chaplin's authorized reissue finally came in 1969.

United Artists opened The Circus at the 72nd Street Playhouse on December 15, 1969. It was the first time a major distributor had gambled on a silent movie in years. Other Chaplins had played US dates in the late fifties. The Gold Rush and Modern Times were briefly available under the auspices of Lopert Pictures, a UA sub, but these had limited playdates. The Gold Rush got by on 338 engagements and brought back $89,000 in domestic rentals during 1959, hardly an indication that the public was ready to embrace Chaplin again. The Circus re-issue wound up going in the tank with just $97,000 in domestic rentals (though foreign reached $921,000). Prints and advertising would have eaten up most of that, as UA did prepare new posters and trailers for the revival. The finish line was flat rentals at kiddie matinees. After 808 playdates, The Circus was unceremoniously dumped (compare that number with other UA releases of the period --- Battle Of Britain had 9,885 dates and The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes, another flop, 3,307). A pity so few (stateside) people saw a movie for which Chaplin supplied an all new musical score, and pristine 35mm prints to showcase it. United Artists' loss was the private collector’s gain, however, for within months, 8 and 16mm pirated negatives were surfacing in underground labs across the country, and The Circus was available for (albeit unauthorized) purchase. Mine was in 8mm, and the cost was $40. The dealer from whom I acquired this hot potato lived in a trailer just beyond the fence of a well-known insane asylum down in the eastern part of the state. He even provided a reel-to-reel tape of Chaplin’s new score to go with the feature. That was in 1971. By 1974, I’d graduated to a 16mm bootleg from a seller whose address was somewhere in the California desert (perhaps near that sweltering location where Stroheim shot Greed? --- you'd like to think so). This time I paid $140. Playing it for a fifty cent admission at my college that year, I half expected Chaplin himself to swoop off Swiss alps with his team of lawyers. Those prints are long gone now, and The Circus is readily available, like so many once inaccessible titles, on DVD. I sometimes wonder if our pleasure in films like this might have been enhanced by the sheer difficulty of seeing them. Watching The Circus again this week was enjoyable enough for me, but I can’t say the experience approached the excitement of unspooling that renegade 8mm print back in 1971, and trying to synchronize the sometimes recalcitrant tape that accompanied it!

United Artists opened The Circus at the 72nd Street Playhouse on December 15, 1969. It was the first time a major distributor had gambled on a silent movie in years. Other Chaplins had played US dates in the late fifties. The Gold Rush and Modern Times were briefly available under the auspices of Lopert Pictures, a UA sub, but these had limited playdates. The Gold Rush got by on 338 engagements and brought back $89,000 in domestic rentals during 1959, hardly an indication that the public was ready to embrace Chaplin again. The Circus re-issue wound up going in the tank with just $97,000 in domestic rentals (though foreign reached $921,000). Prints and advertising would have eaten up most of that, as UA did prepare new posters and trailers for the revival. The finish line was flat rentals at kiddie matinees. After 808 playdates, The Circus was unceremoniously dumped (compare that number with other UA releases of the period --- Battle Of Britain had 9,885 dates and The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes, another flop, 3,307). A pity so few (stateside) people saw a movie for which Chaplin supplied an all new musical score, and pristine 35mm prints to showcase it. United Artists' loss was the private collector’s gain, however, for within months, 8 and 16mm pirated negatives were surfacing in underground labs across the country, and The Circus was available for (albeit unauthorized) purchase. Mine was in 8mm, and the cost was $40. The dealer from whom I acquired this hot potato lived in a trailer just beyond the fence of a well-known insane asylum down in the eastern part of the state. He even provided a reel-to-reel tape of Chaplin’s new score to go with the feature. That was in 1971. By 1974, I’d graduated to a 16mm bootleg from a seller whose address was somewhere in the California desert (perhaps near that sweltering location where Stroheim shot Greed? --- you'd like to think so). This time I paid $140. Playing it for a fifty cent admission at my college that year, I half expected Chaplin himself to swoop off Swiss alps with his team of lawyers. Those prints are long gone now, and The Circus is readily available, like so many once inaccessible titles, on DVD. I sometimes wonder if our pleasure in films like this might have been enhanced by the sheer difficulty of seeing them. Watching The Circus again this week was enjoyable enough for me, but I can’t say the experience approached the excitement of unspooling that renegade 8mm print back in 1971, and trying to synchronize the sometimes recalcitrant tape that accompanied it!

Special Thanks to Dr. Karl Thiede for invaluable data and assistance with this article.

AIP Loses Its Innocence

AIP Loses Its Innocence Few of us would propose Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine as one of the seminal films of the sixties, but from the standpoint of American-International Pictures and exhibition in general, it does represent a turning point. Within months after Goldfoot’s release (November 1965), AIP would abandon virtually all of its old formulas and embrace what we now remember as The Sixties. Consider the cultural divide between The Ghost In The Invisible Bikini (released April 1966) and The Wild Angels (July of the same year). A weakened Production Code was being dismantled in favor of an eventual ratings system. Nicholson and Arkoff saw all of this coming and overhauled their schedule to meet it. The rubble left behind included beach movies, strongman epics, Corman/Poe thrillers --- all those beloved staples we'd associated with AIP would be replaced with bikers, protesters, retro-gangsters spun off Bonnie and Clyde --- even the posters got ugly. I remember being shocked, but more depressed, at seeing The Wild Angels. There’d be no crossing the divide back to those AIP pictures I’d enjoyed but a year before. If it was possible for a boy of twelve to lament a lost youth and innocence, then I most surely did upon seeing this one. Goldfoot played against the setting sun of the fun sixties, when The Four Seasons, Beach Boys, and early Beatles provided background music for life that was more an extension of the fifties than an indication of darker things to come. No doubt there were hints of changes on the horizon, but I didn’t see them during that winter of 1966 when Goldfoot played the Liberty. Neither, I suspect, did showmen whose grass-roots ballyhoo as shown here would itself disappear from the exhibition scene.

Few of us would propose Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine as one of the seminal films of the sixties, but from the standpoint of American-International Pictures and exhibition in general, it does represent a turning point. Within months after Goldfoot’s release (November 1965), AIP would abandon virtually all of its old formulas and embrace what we now remember as The Sixties. Consider the cultural divide between The Ghost In The Invisible Bikini (released April 1966) and The Wild Angels (July of the same year). A weakened Production Code was being dismantled in favor of an eventual ratings system. Nicholson and Arkoff saw all of this coming and overhauled their schedule to meet it. The rubble left behind included beach movies, strongman epics, Corman/Poe thrillers --- all those beloved staples we'd associated with AIP would be replaced with bikers, protesters, retro-gangsters spun off Bonnie and Clyde --- even the posters got ugly. I remember being shocked, but more depressed, at seeing The Wild Angels. There’d be no crossing the divide back to those AIP pictures I’d enjoyed but a year before. If it was possible for a boy of twelve to lament a lost youth and innocence, then I most surely did upon seeing this one. Goldfoot played against the setting sun of the fun sixties, when The Four Seasons, Beach Boys, and early Beatles provided background music for life that was more an extension of the fifties than an indication of darker things to come. No doubt there were hints of changes on the horizon, but I didn’t see them during that winter of 1966 when Goldfoot played the Liberty. Neither, I suspect, did showmen whose grass-roots ballyhoo as shown here would itself disappear from the exhibition scene.

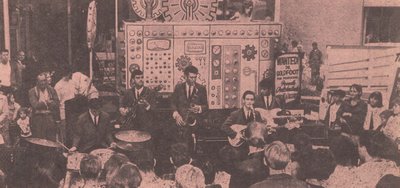

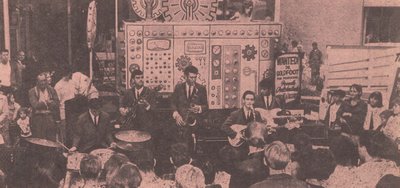

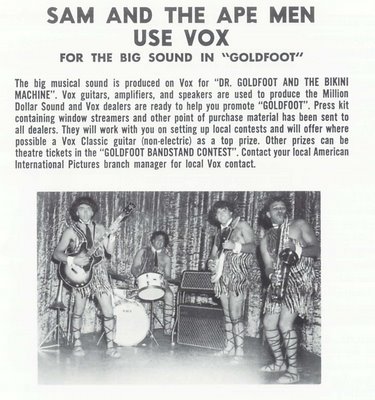

Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine had the sort of Wow opening in Milwaukee they don’t get anymore. Back then, every arm of media opened wide to enthusiastic campaigns like this one. The Palace Theatre had a teenage couple parading downtown streets clad in the film’s signature gold tuxedo with matching shoes. Dr. Goldfoot "money bags" were presented to various news editors when the youths dropped in on Milwaukee dailies. Chocolate coins (wrapped in gold foil, natch) and gold balloons soon adorned copy desks as reporters tied in with the Palace for advance Goldfoot promotion. The kids also hit local TV stations, where vid personalities featured them along with clips from the movie. Since this was a December opening for Milwaukee, Goldfoot figured into the annual Christmas parade by way of a yellow convertible (closest thing they had to gold, I suppose) festooned with signs promoting the show. Radio giveaways included watches, cameras, guitars, shoes, and nylons, all of these contests touting Goldfoot. There were four "teenage rock and roll bands" performing nightly in the Palace lobby (though hopefully not at the same time) and kids were encouraged to dance around the concession area. "The famous bikini machine float" (shown as backdrop for the band here) toured drive-ins, and Vox musical instruments allied with AIP to push both the film and their product. Dr. Goldfoot got national exposure when he was paged during three football games broadcast over CBS. The black-and-white kine captures shown here are from an ABC Shindig special which ran November 18, 1965. The Wild, Weird World Of Dr. Goldfoot featured a sort of pocket version of the movie (with musical interludes) in which Tommy Kirk and Aron Kincaid stood in for the feature’s Frankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman. There were surprisingly no scenes from the feature itself, though Vincent Price and Susan Hart did appear to reprise their roles. If you want an idea of how primitive network television could look as late as 1965, by all means check this out. It’s included as an extra on Vincent Price --- The Sinister Image, a DVD collection of interviews and V.P. ephemera.

Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine had the sort of Wow opening in Milwaukee they don’t get anymore. Back then, every arm of media opened wide to enthusiastic campaigns like this one. The Palace Theatre had a teenage couple parading downtown streets clad in the film’s signature gold tuxedo with matching shoes. Dr. Goldfoot "money bags" were presented to various news editors when the youths dropped in on Milwaukee dailies. Chocolate coins (wrapped in gold foil, natch) and gold balloons soon adorned copy desks as reporters tied in with the Palace for advance Goldfoot promotion. The kids also hit local TV stations, where vid personalities featured them along with clips from the movie. Since this was a December opening for Milwaukee, Goldfoot figured into the annual Christmas parade by way of a yellow convertible (closest thing they had to gold, I suppose) festooned with signs promoting the show. Radio giveaways included watches, cameras, guitars, shoes, and nylons, all of these contests touting Goldfoot. There were four "teenage rock and roll bands" performing nightly in the Palace lobby (though hopefully not at the same time) and kids were encouraged to dance around the concession area. "The famous bikini machine float" (shown as backdrop for the band here) toured drive-ins, and Vox musical instruments allied with AIP to push both the film and their product. Dr. Goldfoot got national exposure when he was paged during three football games broadcast over CBS. The black-and-white kine captures shown here are from an ABC Shindig special which ran November 18, 1965. The Wild, Weird World Of Dr. Goldfoot featured a sort of pocket version of the movie (with musical interludes) in which Tommy Kirk and Aron Kincaid stood in for the feature’s Frankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman. There were surprisingly no scenes from the feature itself, though Vincent Price and Susan Hart did appear to reprise their roles. If you want an idea of how primitive network television could look as late as 1965, by all means check this out. It’s included as an extra on Vincent Price --- The Sinister Image, a DVD collection of interviews and V.P. ephemera.

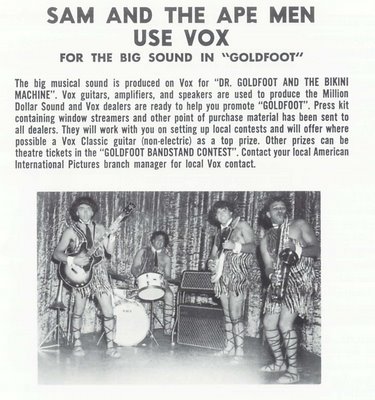

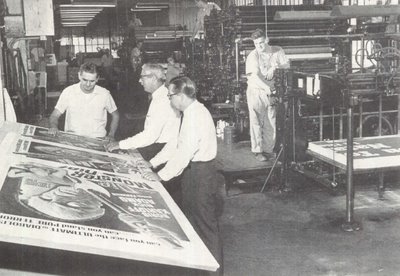

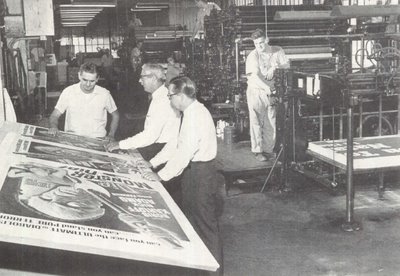

Sam and The Ape-Men is a band I Google-searched. Other than a single Goldfoot reference, nothing came up. They’re featured during a nightclub sequence in the movie, and yes, they wear animal skins. I’m not aware of AIP having released a soundtrack album for Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine, so there’s no certainty as to whether any of Sam’s work survives on vinyl or CD. The title song, however, was recorded by the Supremes. It’s listed as previously unreleased and available in a CD box set released in 2000. The feature itself is a sort of unholy wedding between spy spoofery and the horror genre, with Beach Party personnel stopping in for cameos. Much of Goldfoot’s behind-the-camera talent dated back to Griffith’s day. Director Norman Taurog was a veteran of both Larry Semon silents and Jerry Lewis rib-ticklers. There are actually sight gags with a Murphy bed here, possibly the last time such a prop would be used in a contempo-set comedy. Scriptwriter Elwood Ullman, having penned for Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and the Stooges, furnishes routines that interlock nicely with any number of two-reelers playing television at the time Dr. Goldfoot was released, while verbal references call up (distant) memories of the old Fitzpatrick-Traveltalk series that MGM had discontinued years before. The big San Francisco-based chase finish is an extravagance one wouldn’t expect from AIP, but coming just two years after It’s a Mad … World and in the midst of far more energetic pursuits being staged (routinely) at Disney, it comes off a distant second. Frankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman, both neatly attired in suit and tie, are as distinctly retro as the Blues Brothers would so self-consciously be in the late seventies. Ray gun sound effects are borrowed from MGM’s Forbidden Planet track, and Hickman’s strapped down on the still-standing Pit and Pendulum table, augmented by long-shot footage of John Kerr in a similar predicament from the 1961 thriller (I remember sitting in the theatre wishing I was watching that rather than Dr. Goldfoot). The rentals for Goldfoot ran pretty even with what the beach series had been getting. 1.1 million was the domestic take, a little less than How To Stuff A Wild Bikini (1.3), but ahead of the disappointing number that finished off that series (The Ghost In The Invisible Bikini with $745,000). American-International’s poster art was often as not the most memorable aspect of these shows. The photo here shows the quality control crew at National Screen’s Continental Litho plant in Cleveland, Ohio (poster collectors will surely recognize that name) checking out just printed sheets for Die, Monster, Die, an AIP release that opened a month before Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine.

Sam and The Ape-Men is a band I Google-searched. Other than a single Goldfoot reference, nothing came up. They’re featured during a nightclub sequence in the movie, and yes, they wear animal skins. I’m not aware of AIP having released a soundtrack album for Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine, so there’s no certainty as to whether any of Sam’s work survives on vinyl or CD. The title song, however, was recorded by the Supremes. It’s listed as previously unreleased and available in a CD box set released in 2000. The feature itself is a sort of unholy wedding between spy spoofery and the horror genre, with Beach Party personnel stopping in for cameos. Much of Goldfoot’s behind-the-camera talent dated back to Griffith’s day. Director Norman Taurog was a veteran of both Larry Semon silents and Jerry Lewis rib-ticklers. There are actually sight gags with a Murphy bed here, possibly the last time such a prop would be used in a contempo-set comedy. Scriptwriter Elwood Ullman, having penned for Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and the Stooges, furnishes routines that interlock nicely with any number of two-reelers playing television at the time Dr. Goldfoot was released, while verbal references call up (distant) memories of the old Fitzpatrick-Traveltalk series that MGM had discontinued years before. The big San Francisco-based chase finish is an extravagance one wouldn’t expect from AIP, but coming just two years after It’s a Mad … World and in the midst of far more energetic pursuits being staged (routinely) at Disney, it comes off a distant second. Frankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman, both neatly attired in suit and tie, are as distinctly retro as the Blues Brothers would so self-consciously be in the late seventies. Ray gun sound effects are borrowed from MGM’s Forbidden Planet track, and Hickman’s strapped down on the still-standing Pit and Pendulum table, augmented by long-shot footage of John Kerr in a similar predicament from the 1961 thriller (I remember sitting in the theatre wishing I was watching that rather than Dr. Goldfoot). The rentals for Goldfoot ran pretty even with what the beach series had been getting. 1.1 million was the domestic take, a little less than How To Stuff A Wild Bikini (1.3), but ahead of the disappointing number that finished off that series (The Ghost In The Invisible Bikini with $745,000). American-International’s poster art was often as not the most memorable aspect of these shows. The photo here shows the quality control crew at National Screen’s Continental Litho plant in Cleveland, Ohio (poster collectors will surely recognize that name) checking out just printed sheets for Die, Monster, Die, an AIP release that opened a month before Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine.

American-International was given to grandiose announcements of future projects. Since the early sixties, they’d promised "roadshow" specials. Now it was May 1966 and AIP was entering into a grand scale phase, which would begin with three films in the three million-dollar class. Top name talents and top directors would lead off with Rocket To the Moon, a Jules Verne adaptation starring Bing Crosby as P.T. Barnum. It was only weeks before European location shooting began that Crosby dropped out and Burl Ives was substituted. The resulting picture, released finally as Those Fantastic Flying Fools, and at a cost of far less than three million, was a disaster for AIP ($282,000 in domestic rentals). There were large-scale musicals on tap --- one of them a major Broadway classic, according to press releases. A high-camp hillbilly comedy was budgeted at $1.25 million (itself more than AIP had thus far spent on any production), and there was even a remake of The Golem planned! All of this was scuttled when The Wild Angels broke out in July. This was a smash hit of the sort they’d never had before. $4.290 million in domestic rentals was more than twice the money AIP had realized on their biggest previous success, Beach Party. By the end of September, the company would announce an immediate slate of "protest" pictures dealing dramatically with realistic commentary on our society and times. James Nicholson (shown here with future wife and Goldfoot star Susan Hart) said these pictures would not be aimed at the youth market, but would instead fit into the category of general audience pictures similar to "The Wild Angels." Nicholson refused to disclose specific details in the interest of protecting the subject matter (!). In the meantime, they’d still be handling Thunder Alley, a follow-up to the very successful Fireball 500, and Dr. Goldfoot and The Girl Bombs, an import sequel that flopped. Within the year, beach parties were out and bikers were in. Little kids (including myself) that made up a large portion of the audience for shows like Dr. Goldfoot were now confronted with Born Losers and The Trip. AIP was happy enough to leave the youngsters behind, as the protest pics brought in far more teenage (and adult) dollars, enabling the company to finally mount some of those blockbusters they’d been planning, though the crash-and-burn of De Sade probably made them wish they hadn’t.

American-International was given to grandiose announcements of future projects. Since the early sixties, they’d promised "roadshow" specials. Now it was May 1966 and AIP was entering into a grand scale phase, which would begin with three films in the three million-dollar class. Top name talents and top directors would lead off with Rocket To the Moon, a Jules Verne adaptation starring Bing Crosby as P.T. Barnum. It was only weeks before European location shooting began that Crosby dropped out and Burl Ives was substituted. The resulting picture, released finally as Those Fantastic Flying Fools, and at a cost of far less than three million, was a disaster for AIP ($282,000 in domestic rentals). There were large-scale musicals on tap --- one of them a major Broadway classic, according to press releases. A high-camp hillbilly comedy was budgeted at $1.25 million (itself more than AIP had thus far spent on any production), and there was even a remake of The Golem planned! All of this was scuttled when The Wild Angels broke out in July. This was a smash hit of the sort they’d never had before. $4.290 million in domestic rentals was more than twice the money AIP had realized on their biggest previous success, Beach Party. By the end of September, the company would announce an immediate slate of "protest" pictures dealing dramatically with realistic commentary on our society and times. James Nicholson (shown here with future wife and Goldfoot star Susan Hart) said these pictures would not be aimed at the youth market, but would instead fit into the category of general audience pictures similar to "The Wild Angels." Nicholson refused to disclose specific details in the interest of protecting the subject matter (!). In the meantime, they’d still be handling Thunder Alley, a follow-up to the very successful Fireball 500, and Dr. Goldfoot and The Girl Bombs, an import sequel that flopped. Within the year, beach parties were out and bikers were in. Little kids (including myself) that made up a large portion of the audience for shows like Dr. Goldfoot were now confronted with Born Losers and The Trip. AIP was happy enough to leave the youngsters behind, as the protest pics brought in far more teenage (and adult) dollars, enabling the company to finally mount some of those blockbusters they’d been planning, though the crash-and-burn of De Sade probably made them wish they hadn’t.

Region 2 Round-Up --- Part One

Region 2 Round-Up --- Part One