Halloween Harvest For 2010 --- Part Two

I wish gimmick horrors like Macabre and The Hypnotic Eye were better regarded so distributors could do special editions. Here's where lobby goings-on were lots more interesting than placid screen (in)action. Those who were there fifty years ago will swear by these, while unfortunates who missed 1958 and 1960 parties, respectively, can only wonder what so much fuss was about, let alone word-of-mouth that made hits of both. Warner Archives is just out with Macabre and The Hypnotic Eye, plus several other Allied Artists released chillers. They represent a live-wired era when movies were sold town-to-town and everyone got fun beyond what merely arrived in 35mm cans. By 1958, another horror pic was just that, and even good ones suffered for the glut. Competition ran hot among fright peddlers, especially now that major companies entered a fray previously left to bottom-feeding American-International and others prospecting small coin. Genre bills were never about big money, but make them cheap enough and profits were there for taking, especially with tickets selling mostly to kids. William Castle saw comeback potential in horror after someone took him to see Diabolique in 1957. Bill speaks to that in his memoir, Step Right Up! I'm Gonna Scare The Pants Off America, published in 1976, and lo and behold, just reprinted. He tells of shooting Macabre for $90,000, shopping the neg around for distribution (no takers) and finally getting Allied Artists to roll dice. According to Bill, the thing ended up grossing five million. I'd doubt that (AA estimated something north of two million), although it was a major '58 shock hit (beating Horror Of Dracula, for one). How Castle promoted Macabre was the best thing about it, of course, so those of us left with just an indifferent movie minus recall of its then-sensation can't help feeling ripped (although Warner's DVD quality is plenty compensating).

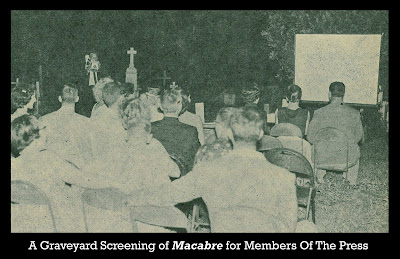

Castle admitted to 50's trade that Macabre wasn't the most wonderful of films, but would more than float boats from showmanship and maybe entertainment angles. Upon arrival at Boston and Chicago openings, Bill rolled up sleeves and personally called one hundred strangers out of the phone book with invites to guest attend Macabre. He stood at boxoffices and handed out thousand dollar life insurance policies for those who died of fright watching the film. A stewardess was picked from each of Bill's incoming flights to receive gratis coverage, plus ducats for a layover screening. Macabre's indemnification was real enough. Lloyds Of London estimated between five and eight patrons might keel over while inside, a risk they were willing to cover provided Castle tender a five G's premium. Fifteen hundred playdates were secured by AA as of April '58, with Macabre holding steady through a crowded summer, despite heavier-hitters come to challenge it. Here was where Bill got the Castle legend rolling. You've got to get out and sell 'em ... the louder the better, he said of this first producing effort. Some ballyhoo was as macabre as his film's title. A second theatre in Corpus Christi, Texas had to be rented, and riot police engaged, to handle teenage mobs aroused by a Friday the 13th midnight run, and their press screening at a so-called "abandoned cemetery" was augmented with buffet tables offering fried ants, rattlesnakes, and grasshoppers, plus tulips and lilies in syrup. Pity a theatre's staff assigned duty of cleaning up that mess.

Macabre earns its title for a story discomfiting even by modern measure. The idea of a child buried alive is no more appealing today than in 1958, but there it is as primary thrust of a frankly unwholesome tale unraveling s-l-o-wly over 72 minutes. For reasons unknown to me, Macabre had been largely out of circulation for years before Warner Archive restored same to us, so this was first time seeing it. A hallmark of William Castle thrillers must surely be utter disdain for sense or logic in a story's telling. Just give us the bumps and closer scrutiny be hanged. At least there's little predicting what happens next. Castle must have sat in his director chair sketching out ads for a selling end to Macabre that engaged him far more than coherent action before cameras. Still, there was no denying Macabre's appeal to morbid tastes, ticket sales inspiring Allied Artists to forge ahead with The Hypnotic Eye, this time sans Castle, but again with gimmickry not unlike what he'd used to sell 1959's in-between House On Haunted Hill, also for AA release. The Hypnotic Eye was unleashed in early 1960 amidst a waning market for stunt horrors, particularly ones lacking color. Balloons were this time handed to incoming youth, inflatable at an arranged point in the film where on-screen Jacques Bergerac demonstrates power of suggestion for his audience. Fifty years later, a lot of patrons still remember the balloon and anticipation of blowing it up for the Hypno-Magic gag. They've also not forgotten horrific scenes of women mutilating themselves while under sinister spell of the titular eye. Even watching from a half-century's distance, those pack a queasy wallop yet.

Boys would be boys, and ones that bragged home of having seen women rinse faces in sulfuric acid might well have been barred from future horror movies by parents understandably appalled, but youth in those days (including myself) were usually wise enough to keep traps shut as to what they'd seen in theatres. Friend Brick Davis made the Liberty scene for The Hypnotic Eye (his father took him) and remembers well the balloon experience. Allied Artists kind of snuck their gimmick through a back door by making it essential to crowd enjoyment of The Hypnotic Eye ... Pass on the balloons, Mr. Exhibitor, and Hypno-Magic falls flat. Showmen were cool with gimmick attractions so long as they didn't cost beyond film rental. Trouble with The Hypnotic Eye and the William Castles was fact of giveaways, wired seats, and skeletons on wires adding expense up front that might not be got back should shows flop. Allied Artists offered balloons at $20 per thousand (with assurance they were being sold at cost), which seems not too unreasonable a risk, but consider fact that rural houses paid that (or barely more) to book the feature itself ... and how many of small-towners could anticipate a thousand patrons for The Hypnotic Eye? I'm envisioning waste cans filled with balloons or youngsters receiving them for many a 1960 attraction that followed The Hypnotic Eye (could a present day search of the Liberty reveal a box of them still in storage?).