Warners and The James Dean Cult --- Part One

Two-thirds of James Dean’s starring work in films was yet to be released when he died on September 30, 1955. The only evidence of his stardom was East Of Eden, and the success of that led to one-sheets prepared for Rebel Without A Cause in which Dean was tagged Overnight Sensation with a future assured playing leads. Never before had a star departed so prematurely. Rudolph Valentino rose, peaked, and began his decline before death intervened and conferred immortality. Son Of The Sheik followed and became rallying point for fans bereaved. Youth snuffed out was (is and always will be) the stuff of morbid fascination for the young surviving. They’ll not be denied a last glimpse. MGM would have shelved the unfinished Saratoga but for letters begging a screen farewell for Jean Harlow. Her older films revived wouldn’t do. Viewers wanted to ponder her closer to the end. The problem was collecting admission for such autopsies without looking ghoulish. That high wire is traversed yet when expensive projects lose a principal just before completion (or release). Warners might well have dug out their Dean files when Heath Ledger died suddenly last January, for what was this but corporate history repeating itself? Would The Dark Knight be all-time Number Two ($491,702,478 so far) had he lived? There were ginger steps over how to sell it. Director Terry Gilliam called WB white sharks shamelessly capitalizing on Ledger’s passing. There’s no easy out when a thing like this happens in merchandising. For all the acclaim given his performance in The Dark Knight, it seems unlikely that Heath Ledger will become a (death) cult figure on the order of James Dean. Times and circumstances are different. The mad rush for Dean echoed frenzied reaction to Valentino’s exit, even as that event flashed hotter (near riots as he lay in state) and burned out quicker. Dean’s built over months after September 30, was nourished with fresh product (Giant being released a year after he died, followed by The James Dean Story in 1957), and lasted longer. He was his own best advance man for the romance of sudden death. It’s fast and clean and you go out in a blaze of glory, said Dean when reporters raised the possibility of early demise on a racetrack. And what of these disquieting poses he’d struck when it seemed photographers recorded his every waking moment? Peering through a noose or nested in a casket, Dean looks intent on getting to the other side ahead of his audience, as if a ticket to cult immortality had already been purchased and he was just waiting for fate to cash it in. Plenty of omens creeped out viewers in hindsight. Dean appeared with Gig Young (as shown here) on behalf of traffic safety in a spot intended for Warner Brothers Presents, the ABC series that played for a single season in 1955-56. It was part of a segment promoting Rebel Without A Cause and was filmed on September 17, 1955, but never televised. Two other promotions featuring Rebel players were broadcast on Warner Brothers Presents (Natalie Wood on October 11 and Jim Backus on November 1), but the Dean footage was shelved and not seen until it was included in The James Dean Story, released nearly two years later.

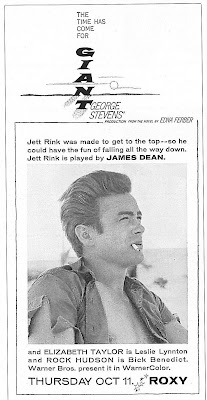

James Dean attended a preview of Rebel Without A Cause within hours of doing the safety spot. Warners’campaign was progressing and references to Dean were very much in terms of present and future tense. A new star was born and there would be many triumphs to come. By October, however, those one-sheets were being sniped over with regards Dean becoming the star of the year, little realizing that he'd become precisely that within a few short months, despite events of September 30. Initial reaction was skittish. The Motion Picture Herald’s Selling Approach column tried putting showmen at ease. We believe that because James Dean was killed in an automobile accident a few weeks ago is no reason why his success as a star should not go on. Don’t encourage your audience or any others to have any such qualms. It is one of the utterly mistaken notions of our industry --- so let’s keep his talent alive on our screens! This was November 5, and Rebel was filling houses everywhere it played. Establishment critics meanwhile weren’t giving Dean a pass just because he’d died. Bosley Crowther at The New York Times cited monotonous Brando imitating among Rebel players, JD not excepted. The perceived apathetic attitude of the American public toward motion pictures inspired a group of Allied Theatre owners to launch their so-called Audience Awards, ballots for which would be filled out in lobbies and tallied by showmen. The "Audies" were essentially grassroot Oscars, a democratic alternative to votes cast by Academy insiders. Elections held during Fall doldrums would culminate in a television spectacular (that never happened) comparable in its impact to the Academy Awards television show, followed by bookings for winning films during notoriously slow pre-Christmas weeks. Among those selected was Tab Hunter as Most Promising Personality for Battle Cry and James Dean as Best Actor for East Of Eden, the latter of which took WB unawares. When I attempted to book "East Of Eden" for a repeat run, I was advised that it had been withdrawn from distribution, complained one exhibitor. A rush order went out to place more James Dean at theatre’s disposal. On December 17, Warners announced a reissue double-bill for East Of Eden with Battle Cry (ad here), their first recognition of a posthumous surge. Incoming letters rose to 8000 a month, many asking for Dean bric-a-brac. Teens nationwide sought the red zippered jacket Jim wore in Rebel Without A Cause. When studio replies suggested it could be had for $22.95 from Mattson’s Hollywood clothier, their having supplied the original, kids made a run on the place. Dean ranked Number One on Photoplay’s popularity poll by Spring 1956, and high school students in thirty-two cities picked the late star as their fave. The run-up to Giant was becoming feverish. Director George Stevens took his usual forever editing that long, long feature, trying cultist’s patience. Warnings were issued that he’d best not cut a frame of Dean’s performance. It’s absolutely weird, said the veteran helmsman. Rebel Without A Cause meanwhile not only maintained but was doing splendid repeat business. Eventual profits of $3.9 million against a modest negative cost of $1.4 put it right behind WB’s biggest hits of 1955, Mister Roberts and Battle Cry. With Giant in the much anticipated offing, was it any wonder so many Dean followers refused to believe he was really dead?

A weird new phenomenon is loose in the land, said TIME magazine on September 3, 1956 (the none-too-flattering article was called Dean Of The One-Shotters). It seemed Dean-mania was getting out of hand. Mainstream bastions took note and were unanimous in their disapproval. The bandwagon that looks disconcertingly like a hearse mirrored concern with an overlay of withering sarcasm. These were journalists, after all, who’d been in the game for years and weren’t about to be taken in by such morbid folly. This is really something new in Hollywood --- Boy meets Ghoul. Were they as miffed over rival magazines selling out aforementioned one shot tributes to Dean (such as vulture pickings shown here)? Ezra Goodman reported for LIFE. Delirium For Dead Star headlined his condemnation of Dean-inspired excesses. By September 24 when the article was published, there were plenty. Humphrey Bogart spoke for an establishment Hollywood ready to apply brakes. If he had lived, he’d never have been able to live up to his publicity, said the actor. Sick of it all George Stevens minced fewer words as Giant’s premiere drew close and he realized many were looking to his epic for a Jimmy fix and little else: A few more films and the public wouldn’t have been so bereft. He shortly would have dimmed his luster. All this as loosely hinged fans insisted their idol walked among us yet. Was Jimmy hiding out in Mexico to conceal disfiguring injuries sustained in the accident? Those sufficiently gullible could hope. Grown-ups expressed concern now that TIME and LIFE sounded their majority’s alarm. Shouldn’t Warners be engaged in healthier enterprise? A still breathing if overworked Tab Hunter suggested they might, as two 1956 releases proposed that ersatz heir to Dean’s following, and boxoffice. Tab, however, lacked JD’s intensity and tragic grandeur. His dreamboat was no substitute for Dean’s storm tossed dramatics, despite the "promising" Battle Cry, and besides, Tab showed all intentions of staying alive to enjoy underpaying benefits of Warners stardom. The Burning Hills and The Girl He Left Behind borrowed Dean’s co-star and hopeful good luck charm Natalie Wood to play opposite Hunter, her Rebel Without A Cause appearance foregrounded in publicity for both. A sadder would-be successor to Dean was nakedly ambitious Nick Adams, his wholehearted immersion in the JD cult raising not a few eyebrows within industry circles. There were two fan magazine tributes under his byline, for which Nick relished mail going up by two hundred letters a week after the first one was published. They’d been close, you see. Jim left Nick poems he’d written, plus scarves, shirts, and belts, none of which the latter was disposed to share with fans. I sleep with a loaded .32 automatic and a .45 automatic in my house. I keep all the stuff hidden in a big strong steel box locked in the attic. Adams hauled the bounty downstairs to pose Dean-like with his treasures, as shown here. I have police protection --- the cops check my house eight to ten times a day.

Giant would open in October 1956, but theatres and drive-ins toward the back of the line made do with limited engagements Warners permitted of Rebel Without A Cause with East Of Eden. James Dean photos came with admissions to many of these, and showmen noted grosses equivalent to first-run business. October also saw the release of soundtracks via MGM Records with Art Mooney and His Orchestra playing music from Dean films. If we know the teenagers, they will go for it, by the millions, said The Motion Picture Herald. Warners meanwhile soft-peddled JD in Giant publicity. Their pressbook referred to him, as before, in the present tense. You’d never know the actor had died after reading press releases the studio prepared. Giant looked to audiences far beyond membership of the Dean cult, whatever that group’s anxiety to see it. Contracted billing required Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson in favored position, but theatre men knew where their bread was buttered, thus marquees, including the Chicago one shown here, brazenly sold Dean as Main Attraction. Newspaper ads were as culpable. Dean’s image alone represented Giant in the Pantheon’s bid as shown here, plus his name was elevated to position above Taylor and Hudson. This sort of exhibitor free-styling was commonplace as everyone sought to cash in on the Dean wave at its height. Boxoffice magazine divined reality in its October 13 review and spelled things out for whoever booked Giant. It is the presence and popularity of James Dean that will prove the most potent factor in attracting ticket buyers, particularly from the teenage groups. Discomfort over a phenomenon bordering on psychosis was offset by prospects of cash in the till. It is his name that will bring the bobby-soxers in droves and will stimulate them into seeing the picture time and time again. Sure enough it was teens pulling four-hours of Giant on repeated shifts. Bolder Dean devotees liberated poster materials out front, valuable publicity in itself for some situations. Minneapolis’ Radio City Theatre found its Giant display minus a James Dean head one morning, prompting rewards to be paid upon its return and placement of a sheriff’s detective to guard a replacement bally. The warning sign now posted (above) was both enticement to purloining fans and those who’d not yet paid admission to see what all the fuss was about. Dean’s relatives were dragged off Indiana farms to thump on Giant’s behalf. His aunt, uncle, and a cousin showed up at an Indianapolis drive-in opening in late November and were duly recognized for service to the trade. It seemed a departed James Dean had no peer, let alone competition, for first placement among teen idols. That would change, and soon, as many theatres coming off Giant playdates changed marquees to herald their next attraction --- Elvis Presley and Love Me Tender.