No actress has emerged since to challenge Bette Davis’ status as First Lady Of The Screen. Market realities no longer allow for such opportunity. If we’re to recognize women who achieved legend status in movies, it will now and forever be necessary to turn clocks back to a studio era when career longevity was put first and careful handling assured popularity over (hopefully) more than just a handful of vehicles. Davis did have rivals at her peak. Their legacies have faded beside hers, but Greer Garson at Metro and Betty Grable at Fox were bigger earners during that wartime peak for female stars. Davis began slow as a money name above the title. Jezebel actually lost $78,000, while forthcomers The Sisters (profit $120,000) and Dark Victory ($580,000 in black ink) pale beside enormous monies the Greer Garson series earned once she caught on at MGM. A Now, Voyager clicked by Warner standards with $4.1 million in worldwide rentals, but Garson in Random Harvest got $8.1 from its worldwide total, and Mrs. Miniver took an astounding $8.8 million worldwide. No Davis film approached such figures. Her biggest for Warners would be A Stolen Life, and the $4.7 million that took worldwide probably has more to do with its all-time boom release year (1946) than any intrinsic value the picture had. Betty Grable musicals at Fox were enormous wartime attractions. Their value then as now seem linked to their necessary function boosting morale and rousing service camp audiences. Few think of Grable or her films offering as much when great musicals are considered, but no one’s did better while the conflict was on. Most wartime Grables realized at least four million worldwide, and two vaulted past five (Coney Island and The Dolly Sisters). Such numerical realities count for nothing toward diminishing Davis’ standing. The fact we’ve had numerous DVD box sets devoted to her and only one (said to have undersold) between Grable and Garson settled clearly the winner. That all three went into sharp decline once peace was declared is attributable partly to moviegoing veto power servicemen exercised once they returned home, plus conditions unrelated to the actresses’ appeal or sudden lack of it. People had other things to think about besides going to films, and many personalities who’d attracted during the war (especially women) saw careers headed for diminuendo.

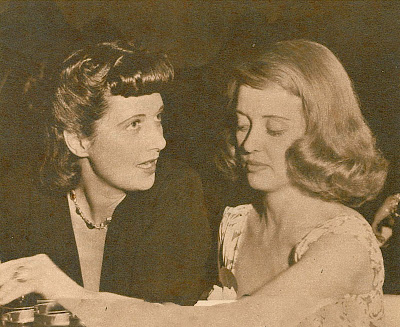

Greer Garson may have been a commercial dominatrix on the home front, but Davis was the truer alpha female (here’s a rare charity event candid of them together). As to musical supremacy, I wonder if BD’s accompaniment didn’t have Grable beat as well. The latter sang and danced, but her music had not the narcotic effect Max Steiner conjured for the Davis pictures. His scores provided flow to link most BD melodramas and comforting familiarity that made them not unlike radio programs one might listen to from week to week. Themes from Now, Voyager spun off into pop vocals and RCA as late as 1974 would successfully market an LP top-lining Steiner’s compositions. Much of the dynamism we associate with Davis might as easily be credited to Steiner. How many of BD’s big scenes play in our memories apart from musical support we remember as vividly? Take away Max and some of Davis’magic goes with him, though it might be as easy saying the same thing with regards all the features he scored. The war that sustained Davis and her brand name in women’s melodrama conferred power upon her no female artist at Warners came close to achieving before or since. She’d fight with weak directors, but resist strong ones as well. Finally it became a matter of assigning helmsmen based less on ability than endurance of her tirades. William Wyler said no more after quarrelling through much of The Little Foxes. From this point, outstanding films would come mostly of chance and Warner polish so expert as to disguise cliché and absurdity otherwise noticeable. Davis recognized the latter and attributed much of the compromise to stringent Code enforcement. For drama trafficking in relationship issues, her output had as much to do with sex as an Abbott and Costello farce at Universal. Dialogue assured innocent outcomes for clinches fading to black, Davis and romantic vis-à-vis confirming later they’ve done nothing to be ashamed of. It was a timid formula bound to catch up with BD once the war ended and audiences demanded content more suggestive of real life. Had the PCA surrendered (or at least relaxed vigilance), she might have hung on to the summit a little longer. As it was, the harder edge of noir sensibility and a reborn Joan Crawford to exploit it would dethrone Davis and finish her stay at the top.

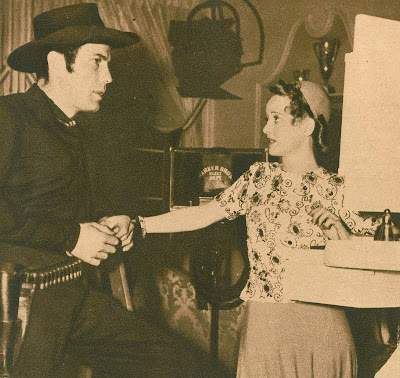

So many declines begin with costs going up and receipts coming down. Bette Davis was an expensive asset for Warners to maintain, even in the best of times. She was getting seven thousand a week and doing one picture a year by 1946. Each went do or die against overhead her salary generated plus generous budgets allotted the films. And now audiences were beginning to file out. Turnstiles ironically went the other direction for newly signed Joan Crawford, whose Mildred Pierce pointed the woman’s melodrama in more violent directions. Davis had killed before on screen, and would again in Deception, but that 1946 release shuddered beneath a $2.8 million negative cost, twice the amount it took to make Mildred Pierce (at $1.4 million). Deception would be the first BD vehicle to lose money ($190,000) since The Private Lives Of Elizabeth and Essex, and with so much expense dragging in her wake, a Davis picture would have to earn tall rentals to bring a profit, an outcome less likely for an aging star in an uncertain market. BD’s age was an issue now. She’d recall said spectre having come to call around the time of Winter Meeting (and yes, she does suddenly look older here), and that would be another Code-hobbled one with losses amounting to a horrific $1.1 million, Warner’s biggest flop since The Horn Blows at Midnight. The Crawfords were meantime doing better. Humoresque, Flamingo Road, and The Damned Don’t Cry all made profits, and it’s no coincidence that most of her vehicles saw JC brandishing iron and/or immersed in criminal and/or underworld activity. There was still a sex potential in Crawford’s screen exploits, and that plus mayhem supplied a formula for this actress more congenial to rougher postwar appetites. When Davis tried addressing Topic A in Beyond The Forest, results were ludicrous even by her own reckoning, but what self-destructive impulse caused her to make even more demands upon employers at said juncture? Had Warners been willing to open ledgers for talent, they might have shown her rivers of red ink on the final four she did for them. Was Davis aware she was negotiating from such a weak position? If so, she shouldn’t have been surprised when Jack Warner called her bluff (or was it?) and agreed to a termination of their contract during Beyond The Forest. Timing could hardly have been worse for any actress going jobless, let alone one past forty whose alcohol and nicotine habits left imprints of hard-living difficult now to conceal.

You’d have thought All About Eve would be the triumph that would keep on giving, but prospects in its wake were sufficiently grim as to negate whatever benefits that 1950 Best Picture winner conferred. Was it the fact of an ensemble cast and hot director that distracted potential employers? We think of Davis as the big noise in that picture today, but it was, after all, George Sanders and Joseph L. Mankiewicz that won awards, while BD had to share Best Actress nominations with Anne Baxter from that show (and she’d not win). Warner flair was missed in Payment On Demand, an RKO release among few (if any) to turn a profit until Whatever Happened To Baby Jane? in 1962. The interim saw much of her on television. Davis would later admit this was sometimes the only work she could get. The First Lady Of The Screen was now like any character actress for whom theatrical leads came seldom. When she got them, returns were tepid. Another Man’s Poison was BD again mixing lethal dosage for the men-folk, but this independent released through UA was cramped, dark and realized only $601,000 in domestic rentals. Her final lead prior to the Baby Jane inspired grotesques, Storm Center, was good for a measly $196,000 domestic. She was still a prestigious guest on television, and the vid avalanche of her old films beginning in 1956 made viewers that much more aware of who she was and what she’d accomplished. Flamboyant gestures laid end-to-end on late, late shows gave birth to a new generation of Davis impressionists. She could write her memoirs now and people would be interested. Good sport BD played along with jokesters like Jack Parr and gave talk show instruction on how best to mimic Bette Davis. Her sense of humor was as much impetus for the comeback as her remarkable performance in Baby Jane. My own generation thought of Davis in terms of horror movies. She (and they) sure delivered in the sixties. Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte was cranking up as we arrived at the Liberty one afternoon from school, just in time to see Davis (apparently) cleaving off Bruce Dern’s hand and head. That’s the sort of thing that earned BD her bonifides from me. I’d recently been shook up just watching the trailer for Dead Ringer, as Davis here sicced her dog on hapless and bleeding Peter Lawford. Was there any stopping this woman? Stations our way weren’t running pre-48 Warners, so I figured Davis for having been pretty much on a killing spree since the thirties. Things got so bad that a neighbor kid’s mother forbade us to go see The Nanny simply because she was in it, a decision reversed only after I assured her that BD’s title character was a benign one inspired by Mary Poppins. Such were the harmless fibs we told to gain entrance to pics with mature content.