Why Are These People Laughing?

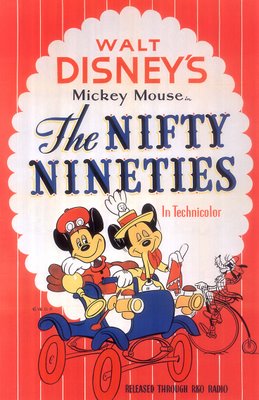

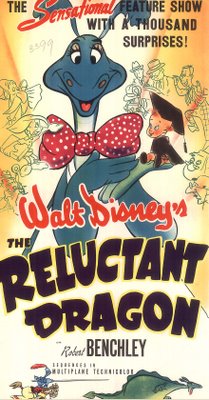

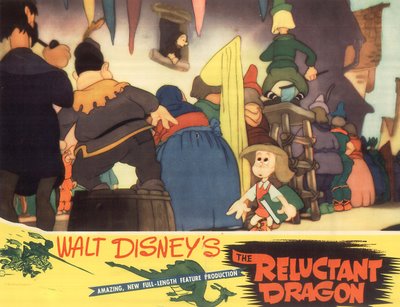

Why Are These People Laughing? Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson are yukking it up with a balcony audience as the latest Donald Duck fades out. The movie is Brief Encounter. By 1945, Donald’s been blowing his stack for ten years, with far less by way of variation over the last five. Joel McCrea and fellow denizens of a chain gang surrender to spasms of mirth over Pluto’s collision with errant sheets of flypaper and a pair of suspenders in 1941’s Sullivan’s Travels. He’d been doing pretty much the same thing since the early thirties. Watching both these features today raises but one question in my mind --- Just what was so funny about these Disney cartoons? If they'd been watching Nasty Quacks (WB) or Red Hot Riding Hood (Avery-MGM), then yes, that laughter might make more sense, but watching Walt’s cartoons today gets not one chuckle from this jaded viewer. Was I born too late? Has our alleged greater sophistication rendered these once hilarious Donald/Mickey/Plutos impotent as laugh-getters, or is it just me? As it happens, my family took receipt of an 8mm print of that Pluto/flypaper segment when we acquired our first Bell&Howell home movie projector back in the late forties (it came gratis with the equipment). This was the first movie I ever threaded up to watch, but I didn’t laugh like Joel McCrea. This week I watched five Disney cartoons released in 1941 --- Canine Caddy (Pluto), The Nifty Nineties and Orphan’s Benefit (Mickey), and A Good Time For A Dime with Truant Officer Donald. I admired them all, but that was it. No other cartoons looked so grand, that’s for sure. When Pluto falls out of a tree, the leaves float down as a thousand individual cels patiently drawn and custom colored. I see pretty ink-and-paint girls (so described in The Reluctant Dragon) in lab coats applying that Disney magic in air-conditioned comfort, but was all this conducive to the sort of humor rival studios were getting into their 1941 cartoons? The collegiate amenities we see during our studio tour in The Reluctant Dragon bespeak comfort, but what about the comedy?

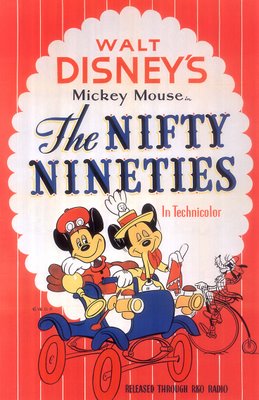

Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson are yukking it up with a balcony audience as the latest Donald Duck fades out. The movie is Brief Encounter. By 1945, Donald’s been blowing his stack for ten years, with far less by way of variation over the last five. Joel McCrea and fellow denizens of a chain gang surrender to spasms of mirth over Pluto’s collision with errant sheets of flypaper and a pair of suspenders in 1941’s Sullivan’s Travels. He’d been doing pretty much the same thing since the early thirties. Watching both these features today raises but one question in my mind --- Just what was so funny about these Disney cartoons? If they'd been watching Nasty Quacks (WB) or Red Hot Riding Hood (Avery-MGM), then yes, that laughter might make more sense, but watching Walt’s cartoons today gets not one chuckle from this jaded viewer. Was I born too late? Has our alleged greater sophistication rendered these once hilarious Donald/Mickey/Plutos impotent as laugh-getters, or is it just me? As it happens, my family took receipt of an 8mm print of that Pluto/flypaper segment when we acquired our first Bell&Howell home movie projector back in the late forties (it came gratis with the equipment). This was the first movie I ever threaded up to watch, but I didn’t laugh like Joel McCrea. This week I watched five Disney cartoons released in 1941 --- Canine Caddy (Pluto), The Nifty Nineties and Orphan’s Benefit (Mickey), and A Good Time For A Dime with Truant Officer Donald. I admired them all, but that was it. No other cartoons looked so grand, that’s for sure. When Pluto falls out of a tree, the leaves float down as a thousand individual cels patiently drawn and custom colored. I see pretty ink-and-paint girls (so described in The Reluctant Dragon) in lab coats applying that Disney magic in air-conditioned comfort, but was all this conducive to the sort of humor rival studios were getting into their 1941 cartoons? The collegiate amenities we see during our studio tour in The Reluctant Dragon bespeak comfort, but what about the comedy?

I found an exhibitor’s comment for Truant Officer Donald in an old Motion Picture Herald. He said it was terrific… reminded him of The Three Little Pigs. Maybe these shorts need a big audience, though when I’ve tried them with college students, they tend to lay flat. Droopy and Wolfy go over big, however. My problem with Disney cartoons is the monotony of them. Donald’s always getting tangled up with machinery, be it a washing machine, lawn mower, what have you. I’ve seen that duck electrocuted more times than I care to recall, but somehow it’s never as funny as when the same thing happens to Daffy over at Warners. Pluto’s forever beset with smaller animals who get the better of him. In Canine Caddy, it was a gopher. I get so tired of damned gophers trumping Pluto. It’s ritual humiliation, and since he’s the audience identification figure, I tend to feel his frustration all the more acutely. Just once I’d like to see Pluto snatch up a gopher at the end of one of these shorts, bite off the head, and enjoy the remains of the carcass before dipping his bloody paw into a finger-bowl and rejoining Mickey. Bon appetit, my man. As for the Mouse, he doesn’t even try to get laughs. The Nifty Nineties is mostly Mickey and Minnie riding around in a sputtering horseless carriage. Any shot in this cartoon would look great framed on your wall, but like Bing said to Bob in All-Star Bond Rally --- Tain’t funny, Hope, tain’t funny. I get the impression, especially after watching The Reluctant Dragon, that Disney artists were somehow timid about going after the big guffaws, as if scoring a real gag might somehow disrupt the well-oiled efficiency of that Burbank Utopia they'd so recently moved into. I don’t think Avery, Tashlin, or Clampett would have lasted long in such a conservative environment. For all of The Reluctant Dragon’s effort in making this look like a wacky and unpredictable place, I still sensed a baleful corporate policing of those pristine halls.

I found an exhibitor’s comment for Truant Officer Donald in an old Motion Picture Herald. He said it was terrific… reminded him of The Three Little Pigs. Maybe these shorts need a big audience, though when I’ve tried them with college students, they tend to lay flat. Droopy and Wolfy go over big, however. My problem with Disney cartoons is the monotony of them. Donald’s always getting tangled up with machinery, be it a washing machine, lawn mower, what have you. I’ve seen that duck electrocuted more times than I care to recall, but somehow it’s never as funny as when the same thing happens to Daffy over at Warners. Pluto’s forever beset with smaller animals who get the better of him. In Canine Caddy, it was a gopher. I get so tired of damned gophers trumping Pluto. It’s ritual humiliation, and since he’s the audience identification figure, I tend to feel his frustration all the more acutely. Just once I’d like to see Pluto snatch up a gopher at the end of one of these shorts, bite off the head, and enjoy the remains of the carcass before dipping his bloody paw into a finger-bowl and rejoining Mickey. Bon appetit, my man. As for the Mouse, he doesn’t even try to get laughs. The Nifty Nineties is mostly Mickey and Minnie riding around in a sputtering horseless carriage. Any shot in this cartoon would look great framed on your wall, but like Bing said to Bob in All-Star Bond Rally --- Tain’t funny, Hope, tain’t funny. I get the impression, especially after watching The Reluctant Dragon, that Disney artists were somehow timid about going after the big guffaws, as if scoring a real gag might somehow disrupt the well-oiled efficiency of that Burbank Utopia they'd so recently moved into. I don’t think Avery, Tashlin, or Clampett would have lasted long in such a conservative environment. For all of The Reluctant Dragon’s effort in making this look like a wacky and unpredictable place, I still sensed a baleful corporate policing of those pristine halls.

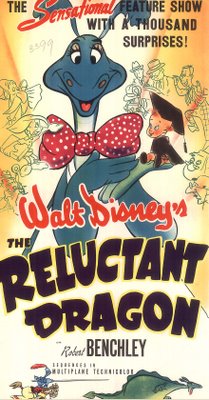

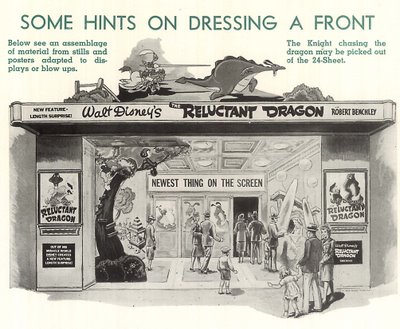

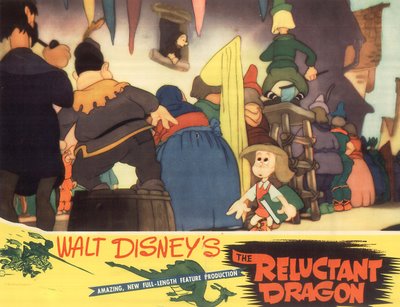

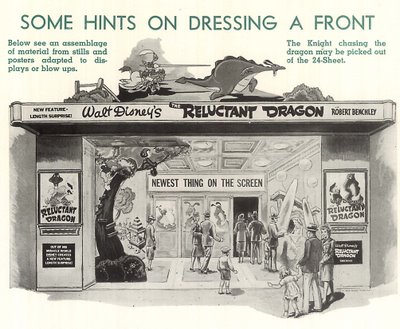

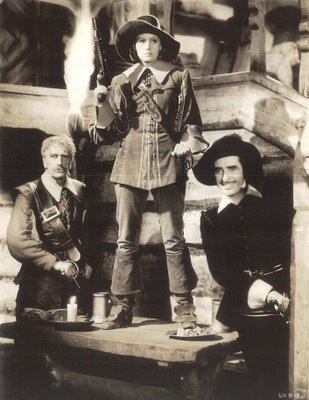

Would I enjoy these cartoons more if Disney hadn’t withheld them when I was growing up? There was no satellite network devoted to them then. The only place to catch these was the Sunday night World Of Color (where main titles were always removed) or reruns of The Mickey Mouse Club (ditto). Theatrical encounters were rare, if that. We might get The Yellowstone Cubs or Ben and Me with Disney features, but seldom a cartoon short. I never really saw Disney cartoons intact until I started collecting 16mm, and then they were pirated prints, or those educational service things where main titles were replaced. At least in the forties they got original RKO credits, even if the cartoons themselves were routine. Humorist Robert Benchley gets to see some of them made in The Reluctant Dragon. This feature is included in the Behind The Scenes At Walt Disney DVD. It’s a must for anyone interested in that studio’s operation and how it looked in 1941. The live action stuff is far more compelling than cojoining animated segments, but Disney had to deliver up some cartoon highlights, for that was his signature product and people still equated his name with drawings that moved. The Reluctant Dragon was regarded as something of a cheater in 1941. It’s really little more than a precursor to a typical Disneyland episode from the fifties, promoting Disney product and glorifying the magic environs of that unique studio setting. No other company would have had sufficient brass to charge admissions for what was essentially a tour of the lot. Benchley’s very presence implies a short subject, as does the animated subjects spotted throughout the 72-minute running time. He’s henpecked and nearly as reluctant as the titular dragon to keep his appointment with legendary Walt. His sour screen wife evokes Judith Anderson. Bob gets a look at comely Frances Gifford and you wonder why he’d ever go back home. Gifford’s playing a Disney staff member (were there such gorgeous women on the payroll at the time?) and she's one of a handful of pro actors drafted to simulate Disney employees. Frank Faylen is another, and live wire Alan Ladd provides spirited narration for the saga of Baby Weems. Ladd’s cast as an artist and story man, and I’d guess his own accomplished radio background got him the job here. Were it not for This Gun For Hire, we might have enjoyed Alan Ladd’s voice behind any number of subsequent True-Life adventures.

Would I enjoy these cartoons more if Disney hadn’t withheld them when I was growing up? There was no satellite network devoted to them then. The only place to catch these was the Sunday night World Of Color (where main titles were always removed) or reruns of The Mickey Mouse Club (ditto). Theatrical encounters were rare, if that. We might get The Yellowstone Cubs or Ben and Me with Disney features, but seldom a cartoon short. I never really saw Disney cartoons intact until I started collecting 16mm, and then they were pirated prints, or those educational service things where main titles were replaced. At least in the forties they got original RKO credits, even if the cartoons themselves were routine. Humorist Robert Benchley gets to see some of them made in The Reluctant Dragon. This feature is included in the Behind The Scenes At Walt Disney DVD. It’s a must for anyone interested in that studio’s operation and how it looked in 1941. The live action stuff is far more compelling than cojoining animated segments, but Disney had to deliver up some cartoon highlights, for that was his signature product and people still equated his name with drawings that moved. The Reluctant Dragon was regarded as something of a cheater in 1941. It’s really little more than a precursor to a typical Disneyland episode from the fifties, promoting Disney product and glorifying the magic environs of that unique studio setting. No other company would have had sufficient brass to charge admissions for what was essentially a tour of the lot. Benchley’s very presence implies a short subject, as does the animated subjects spotted throughout the 72-minute running time. He’s henpecked and nearly as reluctant as the titular dragon to keep his appointment with legendary Walt. His sour screen wife evokes Judith Anderson. Bob gets a look at comely Frances Gifford and you wonder why he’d ever go back home. Gifford’s playing a Disney staff member (were there such gorgeous women on the payroll at the time?) and she's one of a handful of pro actors drafted to simulate Disney employees. Frank Faylen is another, and live wire Alan Ladd provides spirited narration for the saga of Baby Weems. Ladd’s cast as an artist and story man, and I’d guess his own accomplished radio background got him the job here. Were it not for This Gun For Hire, we might have enjoyed Alan Ladd’s voice behind any number of subsequent True-Life adventures.

The best actor here is real-life animator Ward Kimball. He’s at all times relaxed and confident as he walks Benchley through the final stages of a Goofy cartoon and conducts a viewing of the final product on his Moviola. I don’t know how much screen exposure Kimball got in later TV programs (I assume not much, as I don’t recall seeing him), but I’d have to say there was a real missed opportunity here. He’d have made an affable host on some of those Disneyland shows about the history and technique of animation, but I guess there wasn’t sufficient room for both he and the boss. Still, it would seem that Kimball, of all the veteran artists who worked on the lot, had the clearest understanding of Walt’s character and the realities of working at Disney’s (based on interviews I’ve seen). He’d have no doubt been a fascinating guy to sit down and talk with. Quite a sensation knowing that while they were filming this idyllic depiction of life on the studio lot, strike talk was fermenting and disgruntled employees by the hundreds were preparing to walk out on Disney. That's perhaps the most dramatic subtext at work here. Were these people painting their picket signs at home even as they played happy employees for the Technicolor cameras? Walt’s own appearance is brief, but telling. He’s the distracted executive, issuing directives even as Benchley enters his screening sanctorum. Beloved Uncle Walt was still a decade away. This youthful Disney tucks a foot into his seat and regales his guest with a frankly labored cartoon segment to wrap up the show. The Reluctant Dragon we’ve waited for turns out to be an overlong latter-day Silly Symphony in which the title character is inflicted with an Ed Wynn-ish voice, a disagreeable enough prospect when it’s Wynn himself, let alone someone imitating that grating voice. The Reluctant Dragon would subsequently be cut up like so much cordwood and sent out as a variety of short subjects, making it all the more welcome as a finally intact feature on Disney’s DVD.

The best actor here is real-life animator Ward Kimball. He’s at all times relaxed and confident as he walks Benchley through the final stages of a Goofy cartoon and conducts a viewing of the final product on his Moviola. I don’t know how much screen exposure Kimball got in later TV programs (I assume not much, as I don’t recall seeing him), but I’d have to say there was a real missed opportunity here. He’d have made an affable host on some of those Disneyland shows about the history and technique of animation, but I guess there wasn’t sufficient room for both he and the boss. Still, it would seem that Kimball, of all the veteran artists who worked on the lot, had the clearest understanding of Walt’s character and the realities of working at Disney’s (based on interviews I’ve seen). He’d have no doubt been a fascinating guy to sit down and talk with. Quite a sensation knowing that while they were filming this idyllic depiction of life on the studio lot, strike talk was fermenting and disgruntled employees by the hundreds were preparing to walk out on Disney. That's perhaps the most dramatic subtext at work here. Were these people painting their picket signs at home even as they played happy employees for the Technicolor cameras? Walt’s own appearance is brief, but telling. He’s the distracted executive, issuing directives even as Benchley enters his screening sanctorum. Beloved Uncle Walt was still a decade away. This youthful Disney tucks a foot into his seat and regales his guest with a frankly labored cartoon segment to wrap up the show. The Reluctant Dragon we’ve waited for turns out to be an overlong latter-day Silly Symphony in which the title character is inflicted with an Ed Wynn-ish voice, a disagreeable enough prospect when it’s Wynn himself, let alone someone imitating that grating voice. The Reluctant Dragon would subsequently be cut up like so much cordwood and sent out as a variety of short subjects, making it all the more welcome as a finally intact feature on Disney’s DVD.

Merry Greenbriar Christmas For 2006... says Betty Grable (1942) and the Lane Sisters (Rosemary and Priscilla -- 1938). Back on Wednesday, December 27 (Our First Birthday).

Merry Greenbriar Christmas For 2006... says Betty Grable (1942) and the Lane Sisters (Rosemary and Priscilla -- 1938). Back on Wednesday, December 27 (Our First Birthday).

Greenbriar's Five Days Of Christmas --- Part FourChristmas Eve guests having just cleared out, there's finally a moment to post today's entries. Clifton Webb poses here as an unlikely Santa Claus, and that's MGM lovely Maureen O' Sullivan in a mid-thirties Yuletide setting. Hope you're all having a great holiday so far ...

Greenbriar's Five Days Of Christmas --- Part FourChristmas Eve guests having just cleared out, there's finally a moment to post today's entries. Clifton Webb poses here as an unlikely Santa Claus, and that's MGM lovely Maureen O' Sullivan in a mid-thirties Yuletide setting. Hope you're all having a great holiday so far ...

Greenbriar's Five Days Of Christmas --- Part ThreeToday's selections include Donna Reed during her MGM period. This pose dates from 1945, and tied in with her appearance in John Ford's They Were Expendable. The Gloria Jean color portrait graced holiday editions of fan magazines circa the early forties. More to come tomorrow!

Greenbriar's Five Days Of Christmas --- Part ThreeToday's selections include Donna Reed during her MGM period. This pose dates from 1945, and tied in with her appearance in John Ford's They Were Expendable. The Gloria Jean color portrait graced holiday editions of fan magazines circa the early forties. More to come tomorrow!

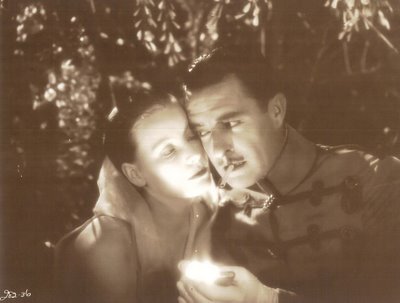

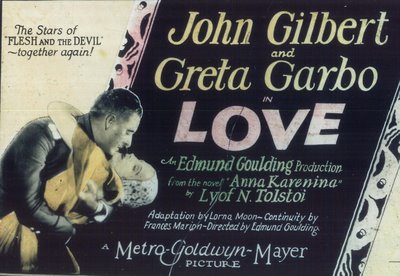

Greta Garbo --- Part TwoIt wouldn’t do for other players to take up Garbo’s distant ways, as there was water but for few at the anti-stardom well (folks never liked their idols standoffish). G.G. drew from that successfully from almost the beginning, but how does that solitary image reconcile with an allegedly torrid laison with John Gilbert? Could there have been more publicity than truth in their off-screen relationship? It’s just possible Garbo relented for once and sought the press she’d receive for linking with Jack, and Metro would certainly have been complicit, but what of poor Gilbert? Was he played for a chump here? How passionate could this woman have been for any man, when all evidence points to a continuing preference for Mimi back home, and the delights to be had upon their forthcoming Swedish reunion? It seems Gilbert was the only one who bought into the notion of a Great Love, just like in the movies, for that’s the alternate reality Jack lived in most of his adult life. A newly empowered Garbo was meantime rattling studio chains with walkout threats (she wasn’t kidding either), and unilateral scheduling which found her Euro-bound before retakes could be completed on her latest MGM show. No longer could Mayer intimidate with dire warnings of suspension and talk of disobedience and insubordination (typical verbal fallbacks in previous Garbo addressed memos). She merely got on the boat and said she’d be back for $5000 a week … no less. Never was such power so vested in a contract player. Metro would make medicine or feel the wrath of exhibitors. Flesh and The Devil had scored $466,000 in profits, The Divine Woman $354,000 --- Garbo was, along with Chaney, the most consistent profit-getter on the lot.

Greta Garbo --- Part TwoIt wouldn’t do for other players to take up Garbo’s distant ways, as there was water but for few at the anti-stardom well (folks never liked their idols standoffish). G.G. drew from that successfully from almost the beginning, but how does that solitary image reconcile with an allegedly torrid laison with John Gilbert? Could there have been more publicity than truth in their off-screen relationship? It’s just possible Garbo relented for once and sought the press she’d receive for linking with Jack, and Metro would certainly have been complicit, but what of poor Gilbert? Was he played for a chump here? How passionate could this woman have been for any man, when all evidence points to a continuing preference for Mimi back home, and the delights to be had upon their forthcoming Swedish reunion? It seems Gilbert was the only one who bought into the notion of a Great Love, just like in the movies, for that’s the alternate reality Jack lived in most of his adult life. A newly empowered Garbo was meantime rattling studio chains with walkout threats (she wasn’t kidding either), and unilateral scheduling which found her Euro-bound before retakes could be completed on her latest MGM show. No longer could Mayer intimidate with dire warnings of suspension and talk of disobedience and insubordination (typical verbal fallbacks in previous Garbo addressed memos). She merely got on the boat and said she’d be back for $5000 a week … no less. Never was such power so vested in a contract player. Metro would make medicine or feel the wrath of exhibitors. Flesh and The Devil had scored $466,000 in profits, The Divine Woman $354,000 --- Garbo was, along with Chaney, the most consistent profit-getter on the lot.

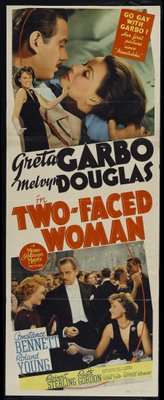

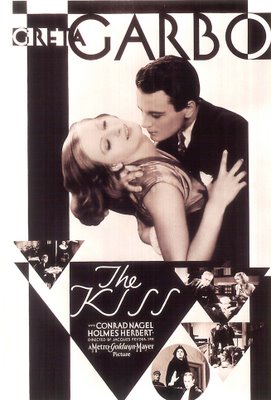

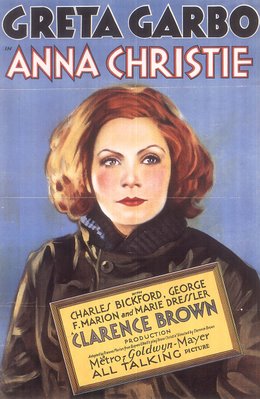

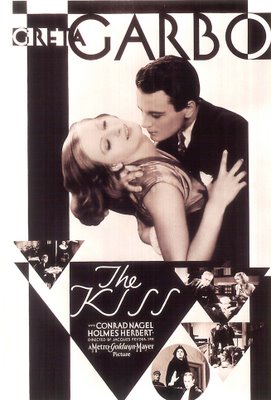

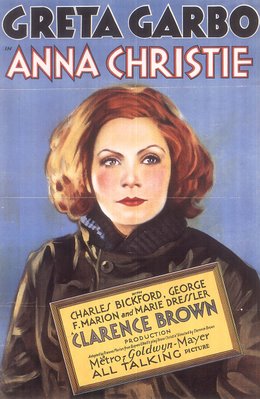

Established silent names made handy cannon fodder for the talkie revolution. Headliners of once solid standing were now so much carrion for the crows. Foreign accents were deadly. Emil Jannings split altogether to avoid embarrassment. Vilma Banky flipped pancakes (!) in her first audion for Goldwyn (This Is Heaven), but Hungarian leading ladies were a hard enough sell in Hungary, let alone here, so Banky retired. Precipitous was a word that might apply to these sooners --- busting out of the gate in early 1929 exposed any number of limitations, and MGM was loathe to feed Garbo into such a career chipper. Her final silent would also be the studio’s last (The Kiss), and that didn’t open until November of 1929. By then, virtually all of Metro’s femme leads had spoken. There was much at stake with Anna Christie. Uncertainty as to its prospects, especially in view of what had happened with so many others, must have been considerable. Reassuring was the fact that MGM’s prowess with sound had gotten Shearer and Crawford over the hump, but even their initial sound numbers couldn’t touch Garbo’s --- Anna Christie took $576,000 in profits to The Trial Of Mary Dugan’s $421,000 and Untamed’s $508,000. The formula for Garbo was rigid, if not ossified. Leading men were non-threatening (though Clark Gable was an alarming one-shot exception). Gavin Gordon, (a young) Robert Montgomery, and (an intimidated) Melvyn Douglas would serve nicely in keeping all eyes upon Greta, for hers was a fragile image after all, and it wouldn’t do to mis-match this actress with too-dynamic leading men (but wouldn’t it be great to see Garbo paired off with Cagney or Warren William in a Warners pre-code?).

Established silent names made handy cannon fodder for the talkie revolution. Headliners of once solid standing were now so much carrion for the crows. Foreign accents were deadly. Emil Jannings split altogether to avoid embarrassment. Vilma Banky flipped pancakes (!) in her first audion for Goldwyn (This Is Heaven), but Hungarian leading ladies were a hard enough sell in Hungary, let alone here, so Banky retired. Precipitous was a word that might apply to these sooners --- busting out of the gate in early 1929 exposed any number of limitations, and MGM was loathe to feed Garbo into such a career chipper. Her final silent would also be the studio’s last (The Kiss), and that didn’t open until November of 1929. By then, virtually all of Metro’s femme leads had spoken. There was much at stake with Anna Christie. Uncertainty as to its prospects, especially in view of what had happened with so many others, must have been considerable. Reassuring was the fact that MGM’s prowess with sound had gotten Shearer and Crawford over the hump, but even their initial sound numbers couldn’t touch Garbo’s --- Anna Christie took $576,000 in profits to The Trial Of Mary Dugan’s $421,000 and Untamed’s $508,000. The formula for Garbo was rigid, if not ossified. Leading men were non-threatening (though Clark Gable was an alarming one-shot exception). Gavin Gordon, (a young) Robert Montgomery, and (an intimidated) Melvyn Douglas would serve nicely in keeping all eyes upon Greta, for hers was a fragile image after all, and it wouldn’t do to mis-match this actress with too-dynamic leading men (but wouldn’t it be great to see Garbo paired off with Cagney or Warren William in a Warners pre-code?).

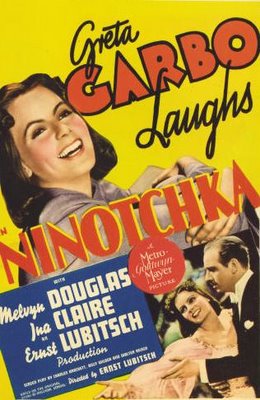

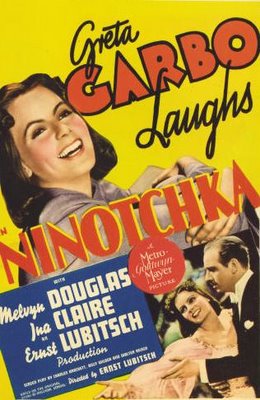

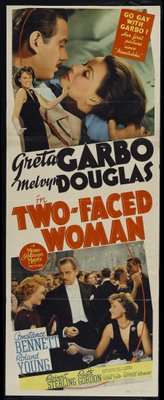

Hollywood and Sweden remained on competing sides of Garbo’s Ping-Pong table. Metro panicked whenever she boarded ship, always fearful she may not come back. Could that explain the two pic a year contract signed in 1933 --- at $250,000 per show? Obviously, these would be specials. Queen Christina was co-penned by one Salka Viertel, whose Svengali influence ensnared a now art-for-art’s sake Garbo. Viewers began noticing a morose overcast in both Garbo and her chosen vehicles. Anna Karenina was good, if unnecessary, especially as she’d done the story before, and with a more effective leading man (Gilbert). Conquest in 1936 would be Garbo’s baptism in red ink. The loss was a stunning 1.3 million, the worst hit Metro took that decade. There were pretenders. Marlene Dietrich was Paramount’s copy-cat, and for a while, it looked as though her exotic vehicles with director Josef Von Sternberg might overtake Garbo, but a fickle public tires quickly even of new things, and after the first few successes, that series was hemorrhaging. MGM was having trouble enough with their genuine article. Unless she could be softened, if not humanized, Garbo herself would run aground. The triumph that was Ninotchka proved she could play comedy, but the real magic was Ernst Lubitsch’s, though he was unable to get her on the phone for a proposed rematch. Bad move on Garbo’s part, for the next (and final) one left her to Metro’s ham-fisted mercies. Two-Faced Woman revealed what a truly bad vehicle can do to even the finest actress. Critics, whom she no doubt read despite assurances to the contrary, were aghast. They’d always considered her one of them, and above such vulgar exhibits. For all their feeling of betrayal, she might as well have co-starred with The Ritz Brothers. What was left of Garbo’s contract was settled with a willing Metro, but did she intend to quit for good?

Hollywood and Sweden remained on competing sides of Garbo’s Ping-Pong table. Metro panicked whenever she boarded ship, always fearful she may not come back. Could that explain the two pic a year contract signed in 1933 --- at $250,000 per show? Obviously, these would be specials. Queen Christina was co-penned by one Salka Viertel, whose Svengali influence ensnared a now art-for-art’s sake Garbo. Viewers began noticing a morose overcast in both Garbo and her chosen vehicles. Anna Karenina was good, if unnecessary, especially as she’d done the story before, and with a more effective leading man (Gilbert). Conquest in 1936 would be Garbo’s baptism in red ink. The loss was a stunning 1.3 million, the worst hit Metro took that decade. There were pretenders. Marlene Dietrich was Paramount’s copy-cat, and for a while, it looked as though her exotic vehicles with director Josef Von Sternberg might overtake Garbo, but a fickle public tires quickly even of new things, and after the first few successes, that series was hemorrhaging. MGM was having trouble enough with their genuine article. Unless she could be softened, if not humanized, Garbo herself would run aground. The triumph that was Ninotchka proved she could play comedy, but the real magic was Ernst Lubitsch’s, though he was unable to get her on the phone for a proposed rematch. Bad move on Garbo’s part, for the next (and final) one left her to Metro’s ham-fisted mercies. Two-Faced Woman revealed what a truly bad vehicle can do to even the finest actress. Critics, whom she no doubt read despite assurances to the contrary, were aghast. They’d always considered her one of them, and above such vulgar exhibits. For all their feeling of betrayal, she might as well have co-starred with The Ritz Brothers. What was left of Garbo’s contract was settled with a willing Metro, but did she intend to quit for good?

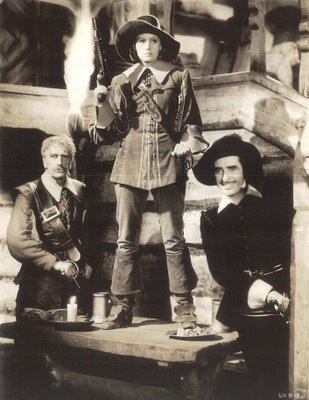

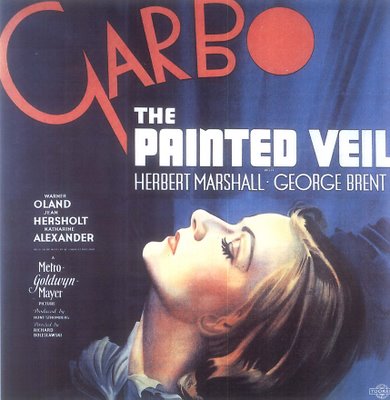

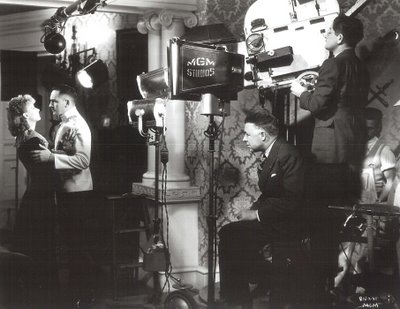

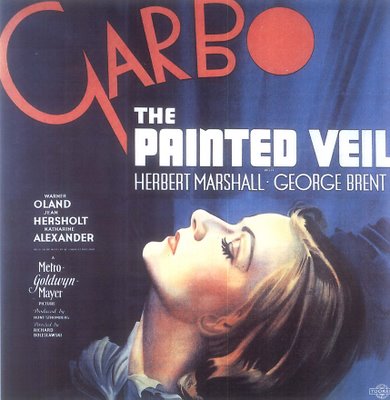

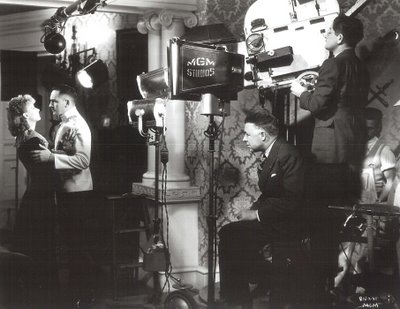

Clarence Brown had been her most frequent director. He said Garbo intended to come back, but things happened and the chance got away. I suspect offers were tentative at best. Prestige she could bring to any table, but could Garbo assure ticket sales? That was surely an issue by the mid-forties. Her old films were considered museum pieces. The best of the talkies evoked literature class in high school. Old-timers spoke of her in reverent tones, and independent producers recognized Garbo as the ultimate "get" for projects in development. Walter Wanger persuaded her to test for one, but as is often the case, money was a bugaboo, and even the supposed magic of Garbo’s name was insufficient to raise it. She became a fast-moving target for rude photographers, hoisting the flag of scarves, floppy hats, menus, whatever was handy to shield that inscrutable face. Friends who blabbed were no longer friends. LIFE magazine celebrated her in the mid-fifties, and MGM exchanges took receipt of new prints in case showmen cared to re-run Garbo features. Art houses steeped in foreign product of uncertain stateside appeal could always depend on this one Hollywood star who’d long ago declared opposition to factory excesses. Greta was still the pin-up girl for disaffected intellectuals and the critics who flattered them. You’d watch her and imagine a font of wisdom, still water running to limitless depths . Quite the contrary, according to those with access. She seems not to have been anything other than ordinary, and niece/nephew relations in fact found her amiable and fun-loving during visits, so maybe all that wanting to be alone business was really just wanting to be left alone where strangers were concerned. Since those strangers included all of us, it was hard not to be a little resentful, but honestly, who’d enjoy being accosted in the street by people one’s never laid eyes on? In the end, a reasonable person would have to grant this woman as much privacy as anyone would be entitled to. Considering she’d been out of the entertainment business for so many years, Garbo had at least that coming to her.Photo CaptionsWith Erich Von Stroheim in As You Desire MeOne-Sheet --- As You Desire MeWith Clark Gable in Susan LenoxOn The Set of Grand Hotel with John BarrymoreThe Astor Theatre's SRO crowd for Queen ChristinaWith C. Aubrey Smith and John Gilbert in Queen ChristinaSix-Sheet art for The Painted VeilClarence Brown directs Garbo and Fredric March in Anna KareninaWith Charles Boyer in ConquestNinotchka Window CardLampooned by Tex Avery and Co. in Warner's Hollywood Steps OutInsert for Two-Faced Woman

Clarence Brown had been her most frequent director. He said Garbo intended to come back, but things happened and the chance got away. I suspect offers were tentative at best. Prestige she could bring to any table, but could Garbo assure ticket sales? That was surely an issue by the mid-forties. Her old films were considered museum pieces. The best of the talkies evoked literature class in high school. Old-timers spoke of her in reverent tones, and independent producers recognized Garbo as the ultimate "get" for projects in development. Walter Wanger persuaded her to test for one, but as is often the case, money was a bugaboo, and even the supposed magic of Garbo’s name was insufficient to raise it. She became a fast-moving target for rude photographers, hoisting the flag of scarves, floppy hats, menus, whatever was handy to shield that inscrutable face. Friends who blabbed were no longer friends. LIFE magazine celebrated her in the mid-fifties, and MGM exchanges took receipt of new prints in case showmen cared to re-run Garbo features. Art houses steeped in foreign product of uncertain stateside appeal could always depend on this one Hollywood star who’d long ago declared opposition to factory excesses. Greta was still the pin-up girl for disaffected intellectuals and the critics who flattered them. You’d watch her and imagine a font of wisdom, still water running to limitless depths . Quite the contrary, according to those with access. She seems not to have been anything other than ordinary, and niece/nephew relations in fact found her amiable and fun-loving during visits, so maybe all that wanting to be alone business was really just wanting to be left alone where strangers were concerned. Since those strangers included all of us, it was hard not to be a little resentful, but honestly, who’d enjoy being accosted in the street by people one’s never laid eyes on? In the end, a reasonable person would have to grant this woman as much privacy as anyone would be entitled to. Considering she’d been out of the entertainment business for so many years, Garbo had at least that coming to her.Photo CaptionsWith Erich Von Stroheim in As You Desire MeOne-Sheet --- As You Desire MeWith Clark Gable in Susan LenoxOn The Set of Grand Hotel with John BarrymoreThe Astor Theatre's SRO crowd for Queen ChristinaWith C. Aubrey Smith and John Gilbert in Queen ChristinaSix-Sheet art for The Painted VeilClarence Brown directs Garbo and Fredric March in Anna KareninaWith Charles Boyer in ConquestNinotchka Window CardLampooned by Tex Avery and Co. in Warner's Hollywood Steps OutInsert for Two-Faced Woman

Greenbriar's Five Days Of Christmas --- Part TwoA note with today's holiday images. Tomorrow morning (Saturday), I'll be posting Glamour Starter --- Greta Garbo --- Part Two, as well as Part Three of the Christmas series, so check back. There's also a terrific new book out on Walt Disney, and it's by far the most exhaustive bio I've ever come across. Neal Gabler is the author, and you get it HERE. Fantastic read.

Greenbriar's Five Days Of Christmas --- Part TwoA note with today's holiday images. Tomorrow morning (Saturday), I'll be posting Glamour Starter --- Greta Garbo --- Part Two, as well as Part Three of the Christmas series, so check back. There's also a terrific new book out on Walt Disney, and it's by far the most exhaustive bio I've ever come across. Neal Gabler is the author, and you get it HERE. Fantastic read.

Greenbriar's Five Days Of ChristmasIn celebration of our first Christmas online, Greenbriar presents a gallery of holiday-themed star portraits which I hope will be unfamiliar to most readers. These are images that have surfaced over the past year and will hopefully be replenished for another run in 2007. I'll be posting each day through Christmas on Monday, so check by. Maybe one of your favorites will show up.

Greenbriar's Five Days Of ChristmasIn celebration of our first Christmas online, Greenbriar presents a gallery of holiday-themed star portraits which I hope will be unfamiliar to most readers. These are images that have surfaced over the past year and will hopefully be replenished for another run in 2007. I'll be posting each day through Christmas on Monday, so check by. Maybe one of your favorites will show up.

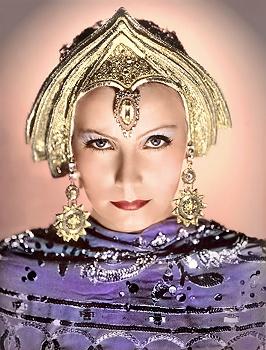

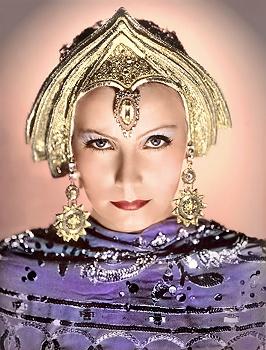

Monday Glamour Starter --- Greta Garbo --- Part OneMen have a hard time getting what the Garbo excitement is/was about. She is not for the uninitiated, and even seasoned buffs have a tendency to leave her off their viewing menu. The centennial celebration(s) of 2005 were welcome to those who cared, but I wondered then how so many book and DVD tributes would fare after those hundred years had passed. For a lot of people, Garbo’s cold as ice, and that’s all there is to her. Much as I like watching the films, I never once envied those screen partners that bedded her. Maybe it’s me, but it never seemed Garbo had an ounce of sex in her, and that’s a legitimate issue when addressing a presumed goddess of love, even if it’s mostly of the unattainable variety. Her unique sensibility was what mattered in the long run, for willing love goddesses were, after all, more easily manufactured. Much of Garbo's persona derived from a European outlook, I suppose, but she conveyed a knowing quality to parts American actresses would have bought into and played straight. She floated somewhere above hackneyed material she recognized for what it was. Sometimes her expression betrayed the boredom and frustration of it all, and you wondered when she’d break through the fourth wall, walk past all of us, and head back home to Sweden. Garbo seemed to traffic in emotions unknown to performing rivals, and yet audiences spotted truth in her work and identified with her responses. That was then, before she ditched celebrity and became a dedicated recluse. There’s still resentment over that frigid resolve and I Want To Be Alone hauteur --- Fine, we never thought you were that great to begin with! To love Garbo is to assume the role of so many hapless men (and women) in her movies, for she’ll never give anything back. The prospect of such unrequited love, particularly when it’s directed toward a public figure (an entertainer yet!) who by any definition of the term should be more generous, is an irritating and off-putting thing. If she’d just once been nice to an interviewer, confessed perhaps upon her eightieth birthday that the whole image had been contrived (and there’s reason to believe it was, largely by Garbo herself), maybe a lot more of us could embrace her today. I like to imagine a forgotten kinescope hidden somewhere at NBC of Dave Garroway and simian sidekick J. Fred Muggs interviewing the elusive Miss Garbo on a 1955 Today segment flanked by Ovalteen commercials and a singing appearance by Johnny Ray. Wouldn’t it be neat if such a thing turned up on YouTube?

Monday Glamour Starter --- Greta Garbo --- Part OneMen have a hard time getting what the Garbo excitement is/was about. She is not for the uninitiated, and even seasoned buffs have a tendency to leave her off their viewing menu. The centennial celebration(s) of 2005 were welcome to those who cared, but I wondered then how so many book and DVD tributes would fare after those hundred years had passed. For a lot of people, Garbo’s cold as ice, and that’s all there is to her. Much as I like watching the films, I never once envied those screen partners that bedded her. Maybe it’s me, but it never seemed Garbo had an ounce of sex in her, and that’s a legitimate issue when addressing a presumed goddess of love, even if it’s mostly of the unattainable variety. Her unique sensibility was what mattered in the long run, for willing love goddesses were, after all, more easily manufactured. Much of Garbo's persona derived from a European outlook, I suppose, but she conveyed a knowing quality to parts American actresses would have bought into and played straight. She floated somewhere above hackneyed material she recognized for what it was. Sometimes her expression betrayed the boredom and frustration of it all, and you wondered when she’d break through the fourth wall, walk past all of us, and head back home to Sweden. Garbo seemed to traffic in emotions unknown to performing rivals, and yet audiences spotted truth in her work and identified with her responses. That was then, before she ditched celebrity and became a dedicated recluse. There’s still resentment over that frigid resolve and I Want To Be Alone hauteur --- Fine, we never thought you were that great to begin with! To love Garbo is to assume the role of so many hapless men (and women) in her movies, for she’ll never give anything back. The prospect of such unrequited love, particularly when it’s directed toward a public figure (an entertainer yet!) who by any definition of the term should be more generous, is an irritating and off-putting thing. If she’d just once been nice to an interviewer, confessed perhaps upon her eightieth birthday that the whole image had been contrived (and there’s reason to believe it was, largely by Garbo herself), maybe a lot more of us could embrace her today. I like to imagine a forgotten kinescope hidden somewhere at NBC of Dave Garroway and simian sidekick J. Fred Muggs interviewing the elusive Miss Garbo on a 1955 Today segment flanked by Ovalteen commercials and a singing appearance by Johnny Ray. Wouldn’t it be neat if such a thing turned up on YouTube?

Should the foregoing seem irreverent, let me hasten to add I think Garbo’s terrific. Seven of her pictures have passed my way these last days and I've not yet tired of her, so don’t let’s confuse me with revisionist voices seeking to dismantle the myth. On the other hand, I’m not of the worshipful school of older critics who built and maintained a shrine that remained intact for all of Garbo’s lifetime, and has only lately been challenged by a new generation of critics coming to her by way of DVD reviews both online and in hep publications like Entertainment Weekly and Premiere. Sometimes I’m shocked at the dismissive ways of modern media when they tear down sacred totems, and someone like Garbo makes a ripe target for non-believers who failed to get the memo about her greatness. Our Web world has unleashed radical voices to take on the critical orthodoxy where Garbo and a lot of others are concerned. There’s quite a gulf between books I’ve read by Andrew Sarris or Alexander Walker and online reevaluations by cheeky youngsters determined to swing the bat on established idols like so many Piñatas. Never have old stars been so fragile as they are today. What’s special about him/her? Were Garbo alive, she might be alarmed by such shifting tides. She’d at least be aware of it, in any case, as I understand there was a clipping service on retainer throughout her life, and during stardom days secretaries were routinely dispatched to go out and buy fan magazines (but only ones that featured her). Wasn’t that Garbo herself that stole into Museum Of Modern Art revivals during the fifties and sixties? They say it was, and apparently she did. Hey, I’ve gone in and polished/revised old Greenbriar articles from months ago. Why shouldn’t Garbo have an occasional glance backward, even though she professed not to care?

Should the foregoing seem irreverent, let me hasten to add I think Garbo’s terrific. Seven of her pictures have passed my way these last days and I've not yet tired of her, so don’t let’s confuse me with revisionist voices seeking to dismantle the myth. On the other hand, I’m not of the worshipful school of older critics who built and maintained a shrine that remained intact for all of Garbo’s lifetime, and has only lately been challenged by a new generation of critics coming to her by way of DVD reviews both online and in hep publications like Entertainment Weekly and Premiere. Sometimes I’m shocked at the dismissive ways of modern media when they tear down sacred totems, and someone like Garbo makes a ripe target for non-believers who failed to get the memo about her greatness. Our Web world has unleashed radical voices to take on the critical orthodoxy where Garbo and a lot of others are concerned. There’s quite a gulf between books I’ve read by Andrew Sarris or Alexander Walker and online reevaluations by cheeky youngsters determined to swing the bat on established idols like so many Piñatas. Never have old stars been so fragile as they are today. What’s special about him/her? Were Garbo alive, she might be alarmed by such shifting tides. She’d at least be aware of it, in any case, as I understand there was a clipping service on retainer throughout her life, and during stardom days secretaries were routinely dispatched to go out and buy fan magazines (but only ones that featured her). Wasn’t that Garbo herself that stole into Museum Of Modern Art revivals during the fifties and sixties? They say it was, and apparently she did. Hey, I’ve gone in and polished/revised old Greenbriar articles from months ago. Why shouldn’t Garbo have an occasional glance backward, even though she professed not to care?

Withdrawn Swedish temperament did not lend itself well to playing with others, particularly on movie sets. You can blow off the press in that business, but it’s unwise being rude to people sharing your monotony on a sound stage. Was it deprived upbringing and unpolished manners that caused Garbo to treat Marion Davies so badly during the latter’s attempt at a friendly on-set visit? Basil Rathbone and Freddie Bartolomew both requested signed portraits at the end of Anna Karenina and were summarily rebuffed. Rathbone remained miffed twenty-five years later penning his memoirs. Movie folk were unaccustomed to snubs like these. It’s one thing to chase off autograph hounds outside the gates, but Garbo made colleagues feel like intruders upon her privacy, and this was not an attitude to foster good will. Had she not been so wildly successful with audiences, I’ve no doubt they’d have relished giving her the pink slip. We’ve all had encounters with the socially challenged, but imagine the frustration of dealing with one who always got to be right. The bigger she grew, the higher she erected those walls. It got to a point where other actors weren’t even permitted to watch her emote, such was Garbo’s determination to keep things private between herself and the camera. All this eccentricity was bred by success, for at the beginning, she’d been reasonably affable and ambitious as the rest, but much of that team spirit was left behind in Sweden, where hard times made her thankful for work in advertising reels and modest features. She’d gotten into drama academy despite humble beginnings, only to become hopelessly smitten with classmate Mimi Pollak (shown with her here). Recently revealed letters track Garbo’s devotion through a lifetime of unrequited (there’s that word again!) passion, but by the looks of pixie Mimi, who could blame her? These lakeside swimsuit antics were shared with two other ingenues, both with seemingly better prospects than a plumpish Garbo, her Wal-Mart shopper heft soon giving way to a studio-mandated all-spinach diet, presumably Sweden’s own draconian Atkin’s substitute. Luck was with her when director Mauritz Stiller offered The Saga Of Gosta Berling, far and away the biggest undertaking yet attempted by a Nordic filmmaker, and one noted by a visiting Louis B. Mayer, whose interest in Stiller was now sidetracked by a fascination with Garbo. Both artists would decamp to America, providing the finishing touch to a Swedish industry already deprived of its other distinguished director, Victor Sjostrom (by way of his own Metro contract). Stiller the mentor and master would come to know that in Hollywood, survival was for the fittest, as would his pupil, though Garbo, whose good luck was, and would remain, unswerving, flourished even as his floundered.

Withdrawn Swedish temperament did not lend itself well to playing with others, particularly on movie sets. You can blow off the press in that business, but it’s unwise being rude to people sharing your monotony on a sound stage. Was it deprived upbringing and unpolished manners that caused Garbo to treat Marion Davies so badly during the latter’s attempt at a friendly on-set visit? Basil Rathbone and Freddie Bartolomew both requested signed portraits at the end of Anna Karenina and were summarily rebuffed. Rathbone remained miffed twenty-five years later penning his memoirs. Movie folk were unaccustomed to snubs like these. It’s one thing to chase off autograph hounds outside the gates, but Garbo made colleagues feel like intruders upon her privacy, and this was not an attitude to foster good will. Had she not been so wildly successful with audiences, I’ve no doubt they’d have relished giving her the pink slip. We’ve all had encounters with the socially challenged, but imagine the frustration of dealing with one who always got to be right. The bigger she grew, the higher she erected those walls. It got to a point where other actors weren’t even permitted to watch her emote, such was Garbo’s determination to keep things private between herself and the camera. All this eccentricity was bred by success, for at the beginning, she’d been reasonably affable and ambitious as the rest, but much of that team spirit was left behind in Sweden, where hard times made her thankful for work in advertising reels and modest features. She’d gotten into drama academy despite humble beginnings, only to become hopelessly smitten with classmate Mimi Pollak (shown with her here). Recently revealed letters track Garbo’s devotion through a lifetime of unrequited (there’s that word again!) passion, but by the looks of pixie Mimi, who could blame her? These lakeside swimsuit antics were shared with two other ingenues, both with seemingly better prospects than a plumpish Garbo, her Wal-Mart shopper heft soon giving way to a studio-mandated all-spinach diet, presumably Sweden’s own draconian Atkin’s substitute. Luck was with her when director Mauritz Stiller offered The Saga Of Gosta Berling, far and away the biggest undertaking yet attempted by a Nordic filmmaker, and one noted by a visiting Louis B. Mayer, whose interest in Stiller was now sidetracked by a fascination with Garbo. Both artists would decamp to America, providing the finishing touch to a Swedish industry already deprived of its other distinguished director, Victor Sjostrom (by way of his own Metro contract). Stiller the mentor and master would come to know that in Hollywood, survival was for the fittest, as would his pupil, though Garbo, whose good luck was, and would remain, unswerving, flourished even as his floundered.

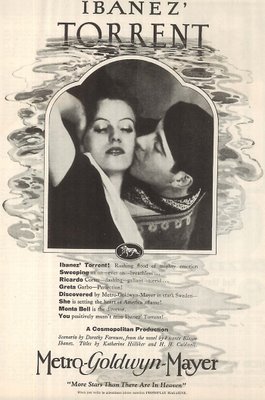

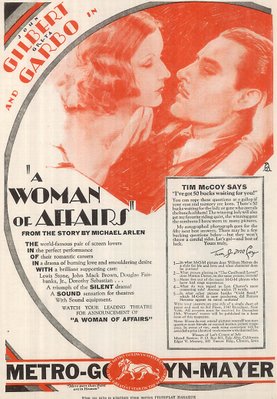

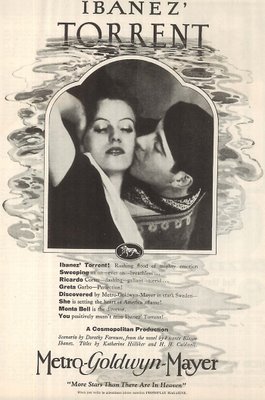

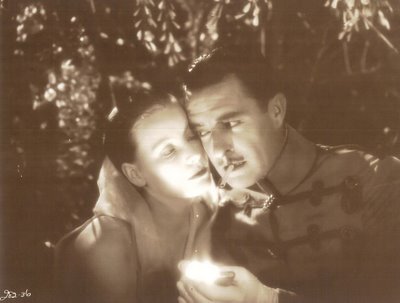

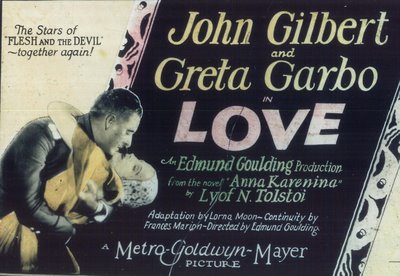

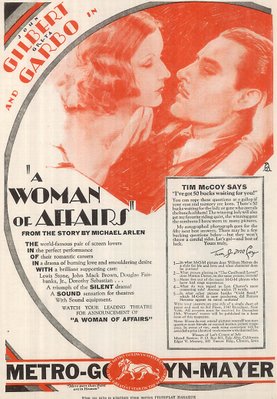

If MGM had a model for developing Garbo, it would likely have been Paramount’s Pola Negri, a German import whose line in Euro-sophistication awakened passions dormant in stateside audiences and gave us all a taste for Continental variations in lovemaking. It was only natural that Garbo be herded in the same direction. Otherwise, why bring her over? We’ve largely forgotten Negri, thanks to films mostly lost, but it’s unlikely she got vehicles so lush as The Torrent and The Temptress, Garbo’s first and second, both based on Blasco Ibanez novels, both showcases for the new star. Any $400 a week player would have died for a start so auspicious, but Garbo complained and made waves from Day One, hating what she referred to as vamp roles and vowing to pack for home unless things improved. Sympathetic Lon Chaney advised her to keep them guessing. Be mysterious and secretive. The conscious decision to do just that defined the remainder of her career, as well as offscreen life. The purposeful withdrawal saved her the embarrassment of dealing with a corporate and social structure she couldn’t begin to understand; silence too deflected awareness of language skills she lacked. What choice but to become The Swedish Sphinx when you’re obliged to drag an interpreter (and hers was doubling as a Mayer snitch!) everywhere you go? From such sour fruit came ambrosia, for Garbo’s pained ambivalence struck a chord with her public and gave them something brand new --- a reluctant movie star. MGM went public with contract disputes, as this played hat and glove with the image they’d fostered. Flesh and The Devil profited from that investment in publicity, for the on and offscreen coupling of Garbo with (much bigger) co-star John Gilbert turned the ignition on a boxoffice clean-up that made these two the screen’s most believable love team. Rival pairings of a Colman/Banky, Gaynor/Farrell sort were persuasive enough as make-believe love matches went, but none generated the heat of a Gilbert/Garbo embrace, its carnality given further emphasis by the leading lady’s fervent way with a kiss (open-mouthed and/or on top of Gilbert). As to standards of further Garbo silents, they remained high, and ever increasing grosses rewarded Metro’s efforts. Love, The Mysterious Lady, and A Woman Of Affairs still play nicely today, and The Single Standard, Wild Orchids, and The Kiss each benefited from recorded music-and-effects during those waning days before talkies. As to these, Garbo must have worn the rabbit’s foot Vilma Banky and Emil Jannings lost, for she was about the only notable foreign-born survivor of the sound purge to come. More about that in Part Two to follow.

If MGM had a model for developing Garbo, it would likely have been Paramount’s Pola Negri, a German import whose line in Euro-sophistication awakened passions dormant in stateside audiences and gave us all a taste for Continental variations in lovemaking. It was only natural that Garbo be herded in the same direction. Otherwise, why bring her over? We’ve largely forgotten Negri, thanks to films mostly lost, but it’s unlikely she got vehicles so lush as The Torrent and The Temptress, Garbo’s first and second, both based on Blasco Ibanez novels, both showcases for the new star. Any $400 a week player would have died for a start so auspicious, but Garbo complained and made waves from Day One, hating what she referred to as vamp roles and vowing to pack for home unless things improved. Sympathetic Lon Chaney advised her to keep them guessing. Be mysterious and secretive. The conscious decision to do just that defined the remainder of her career, as well as offscreen life. The purposeful withdrawal saved her the embarrassment of dealing with a corporate and social structure she couldn’t begin to understand; silence too deflected awareness of language skills she lacked. What choice but to become The Swedish Sphinx when you’re obliged to drag an interpreter (and hers was doubling as a Mayer snitch!) everywhere you go? From such sour fruit came ambrosia, for Garbo’s pained ambivalence struck a chord with her public and gave them something brand new --- a reluctant movie star. MGM went public with contract disputes, as this played hat and glove with the image they’d fostered. Flesh and The Devil profited from that investment in publicity, for the on and offscreen coupling of Garbo with (much bigger) co-star John Gilbert turned the ignition on a boxoffice clean-up that made these two the screen’s most believable love team. Rival pairings of a Colman/Banky, Gaynor/Farrell sort were persuasive enough as make-believe love matches went, but none generated the heat of a Gilbert/Garbo embrace, its carnality given further emphasis by the leading lady’s fervent way with a kiss (open-mouthed and/or on top of Gilbert). As to standards of further Garbo silents, they remained high, and ever increasing grosses rewarded Metro’s efforts. Love, The Mysterious Lady, and A Woman Of Affairs still play nicely today, and The Single Standard, Wild Orchids, and The Kiss each benefited from recorded music-and-effects during those waning days before talkies. As to these, Garbo must have worn the rabbit’s foot Vilma Banky and Emil Jannings lost, for she was about the only notable foreign-born survivor of the sound purge to come. More about that in Part Two to follow.

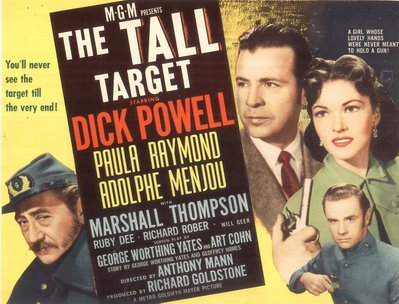

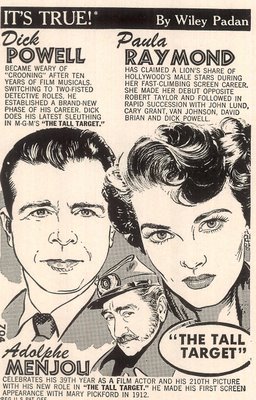

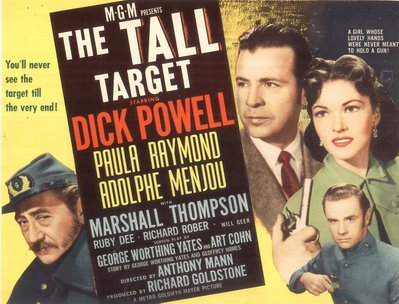

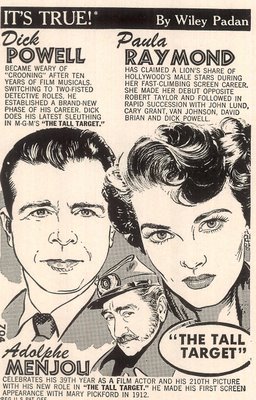

Buried Treasures --- The Tall Target and The Young PhiladelphiansA friend of mine who’s a Hollywood literary agent gave me a peek at a screenplay he’s getting ready to offer. The Lion’s Den deals with certain hidden aspects of the Lincoln assassination and the conspiracy behind it. I’d no idea that the Booth/Lincoln families intersected prior to that night at Ford’s Theatre, and came away from my reading with the hope that someday this script would find its way to the screen. The Lion’s Den also reminded me of another Lincoln-inspired thriller, The Tall Target, in that both utilized historic incidents as a launch for suspense and fast-paced action. In fact, The Tall Target, with its dramatization of a prior attempt on the President’s life, may be the only authentic pre-Civil War noir ever made. Certainly, it’s a unique and gripping depiction of a real-life chapter in Lincoln’s life I’d been unaware of. Anthony Mann directed this between Devil’s Doorway and Bend Of The River. He was quoted as saying that The Tall Target was his attempt to emulate Hitchcock, but these taut 78 minutes were more akin to Mann’s own T-Men, Raw Deal, and Railroaded, three budget noirs upon which his solid reputation was then based. They’d provide the critical and commercial traction to get him into Metro where crime thrillers and gritty westerns were perhaps more plentiful than a lot of us recall today. For a company primarily associated with musicals and glossy star vehicles, MGM veered toward meaner streets after the war. Major names were now doing on-screen police and detective work. Van Johnson, Robert Taylor, and Robert Montgomery were unexpected noir dwellers, but studio overhead demanded a steady flow of product, and the happy result was pictures like Border Incident, Side Street, Devil’s Doorway, and The Tall Target, all directed by Anthony Mann. The fact that three of the four lost money was no reflection on their quality. Border Incident, for instance, was a film without stars (and a final loss of $178,000), while Devil’s Doorway got by on Robert Taylor’s name and a modest $188,000 profit. Critics have mistakenly referred to Mann’s MGM output as "B" pictures. Economical yes, but these weren’t "B’s." Noirs at Metro subsisted on negative costs averaging around $750,000. The Tall Target had a higher tab of $966,000 and lost $594,000. Anthony Mann would need to move up to, and stay with, lucrative westerns with main line star James Stewart in order to become a money director.

Buried Treasures --- The Tall Target and The Young PhiladelphiansA friend of mine who’s a Hollywood literary agent gave me a peek at a screenplay he’s getting ready to offer. The Lion’s Den deals with certain hidden aspects of the Lincoln assassination and the conspiracy behind it. I’d no idea that the Booth/Lincoln families intersected prior to that night at Ford’s Theatre, and came away from my reading with the hope that someday this script would find its way to the screen. The Lion’s Den also reminded me of another Lincoln-inspired thriller, The Tall Target, in that both utilized historic incidents as a launch for suspense and fast-paced action. In fact, The Tall Target, with its dramatization of a prior attempt on the President’s life, may be the only authentic pre-Civil War noir ever made. Certainly, it’s a unique and gripping depiction of a real-life chapter in Lincoln’s life I’d been unaware of. Anthony Mann directed this between Devil’s Doorway and Bend Of The River. He was quoted as saying that The Tall Target was his attempt to emulate Hitchcock, but these taut 78 minutes were more akin to Mann’s own T-Men, Raw Deal, and Railroaded, three budget noirs upon which his solid reputation was then based. They’d provide the critical and commercial traction to get him into Metro where crime thrillers and gritty westerns were perhaps more plentiful than a lot of us recall today. For a company primarily associated with musicals and glossy star vehicles, MGM veered toward meaner streets after the war. Major names were now doing on-screen police and detective work. Van Johnson, Robert Taylor, and Robert Montgomery were unexpected noir dwellers, but studio overhead demanded a steady flow of product, and the happy result was pictures like Border Incident, Side Street, Devil’s Doorway, and The Tall Target, all directed by Anthony Mann. The fact that three of the four lost money was no reflection on their quality. Border Incident, for instance, was a film without stars (and a final loss of $178,000), while Devil’s Doorway got by on Robert Taylor’s name and a modest $188,000 profit. Critics have mistakenly referred to Mann’s MGM output as "B" pictures. Economical yes, but these weren’t "B’s." Noirs at Metro subsisted on negative costs averaging around $750,000. The Tall Target had a higher tab of $966,000 and lost $594,000. Anthony Mann would need to move up to, and stay with, lucrative westerns with main line star James Stewart in order to become a money director.

Much of The Tall Target is viewed through the steam of its arresting locomotive. This was an ideal story for a studio with the best set and costume inventory in the business. A Metro historian more observant than myself could no doubt point out any number of plush chairs, gas lamps, and pocket derringers previously used in a hundred MGM releases dating back to silents. No one calls our attention to all that casual verisimilitude. It’s just there. Those seasoned artisans, many of them having been on the lot for decades, could summon up virtually any moment in history. What treasure troves those warehouses were, and what a tragedy they’d be so callously sold off within a few decades. Star making was a faltering enterprise by 1951. Metro had to know youngsters like Marshall Thompson and Paula Raymond would never make the feature grade, but it’s fascinating to note all the others that show up in largely uncredited roles. Barbara Billingsley? Even she had a run at Metro stardom (seven years of bit parts there between 1945 and 1952) before television conferred immortality. Star Dick Powell would at times seem to be paving the way for forthcoming Charles McGraw in RKO’s The Narrow Margin, its own arrival a matter of months away. There’s even an obnoxious kid riding both trains and supplying near-identical bumps in the narrative. Powell was by now on the cusp of TV entrepreneurship, and The Tall Target would be his final essay in the second career tough-guy persona he’d devised so brilliantly for himself. It’s interesting how a movie like this exists in a sort of obscure twilight, as if waiting for a DVD release to give it new life. You can see it on TCM if you’re willing to catch the train at its designated departure time, or perhaps set your Tivo.

Much of The Tall Target is viewed through the steam of its arresting locomotive. This was an ideal story for a studio with the best set and costume inventory in the business. A Metro historian more observant than myself could no doubt point out any number of plush chairs, gas lamps, and pocket derringers previously used in a hundred MGM releases dating back to silents. No one calls our attention to all that casual verisimilitude. It’s just there. Those seasoned artisans, many of them having been on the lot for decades, could summon up virtually any moment in history. What treasure troves those warehouses were, and what a tragedy they’d be so callously sold off within a few decades. Star making was a faltering enterprise by 1951. Metro had to know youngsters like Marshall Thompson and Paula Raymond would never make the feature grade, but it’s fascinating to note all the others that show up in largely uncredited roles. Barbara Billingsley? Even she had a run at Metro stardom (seven years of bit parts there between 1945 and 1952) before television conferred immortality. Star Dick Powell would at times seem to be paving the way for forthcoming Charles McGraw in RKO’s The Narrow Margin, its own arrival a matter of months away. There’s even an obnoxious kid riding both trains and supplying near-identical bumps in the narrative. Powell was by now on the cusp of TV entrepreneurship, and The Tall Target would be his final essay in the second career tough-guy persona he’d devised so brilliantly for himself. It’s interesting how a movie like this exists in a sort of obscure twilight, as if waiting for a DVD release to give it new life. You can see it on TCM if you’re willing to catch the train at its designated departure time, or perhaps set your Tivo.

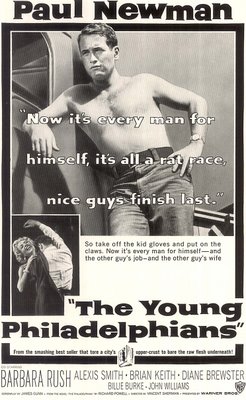

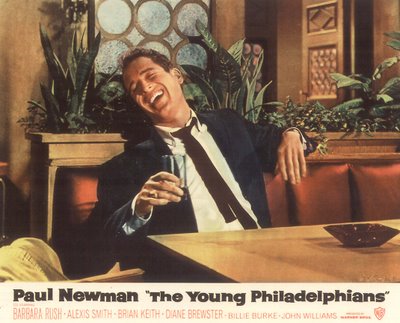

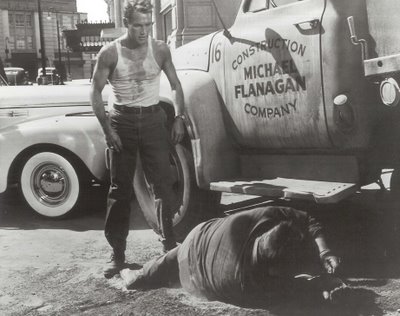

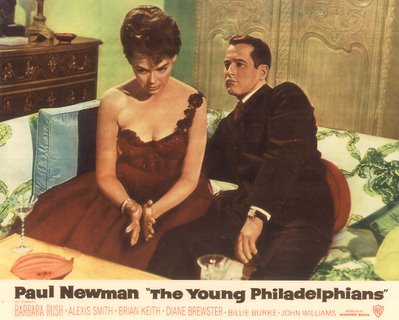

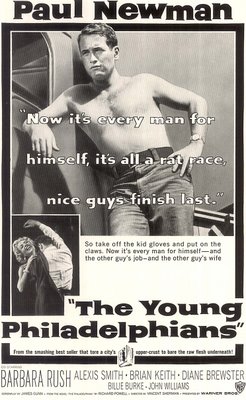

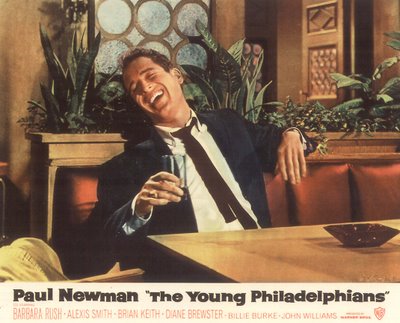

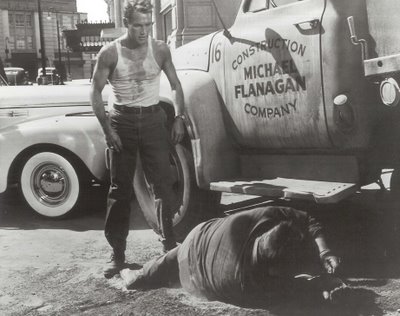

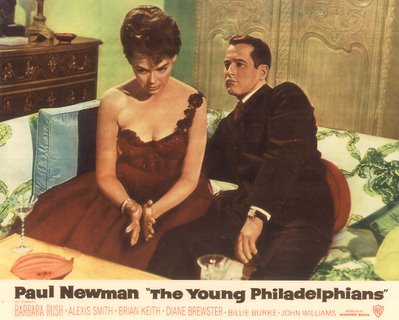

It’s quite a jump from all those resources at MGM’s disposal to the stripped-down economy of The Young Philadelphians, an otherwise tremendously enjoyable Warners melodrama just out on DVD. That title suggests a very specific background, but from the looks of things here, Warners might just as well have set it in Providence, Rhode Island, or Spartanburg, South Carolina. I hadn't the sense of even a second unit having gone to Philadelphia, let alone any of the principal cast venturing there. Warners spent $1.6 million on the negative. The picture doesn’t look cheap, but neither has it the care and production values that would have gone into something along the lines of Paramount’s Vertigo from the previous year, where the San Francisco setting was exploited to its full. Neither could it compete with your typical 20th Fox Cinemascope release, where backgrounds and art direction were vital elements of the whole. For all of that, I still prefer The Young Philadelphians over other selections in the Paul Newman DVD Collection. No other feature captures the Warner ethos quite so well, with its happy collision of up-and-coming stars (Paul Newman), eager beginners (Robert Vaughn, Adam West), and seasoned vets (Otto Kruger, Billie Burke, John Williams … that list is endless). Every time one of those balsa wood doors open, a welcome face emerges, and what inspired casting! Adam West as a Paul Bern-ish husband fleeing the marital bed, "Fred" Eisley just this side of Hawaiian Eye and vid greatness, Paul Picerni years before he’d become one of the most gracious of celebrities at autograph and collector shows. The Young Philadelphians is compulsive viewing. I’d challenge anyone not to like it, from inventive credits that reminded me of the later Ocean’s 11 to a climactic courtroom showdown pitting Newman against Richard Deacon. There’s something inherently pleasing about stories where nice guys are turned ruthless by experience and bitter circumstance. In this case, the worm turns early on and Paul Newman settles into what would become his dominant sixties persona. After prestigious turns in The Long, Hot Summer and Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, this had to have been regarded a comedown by the star. I suspect Paul thinks little more of The Young Philadelphians than he would of The Silver Chalice, yet he’s far more relaxed and natural here than amidst the lugubrious (and non-stop) confrontations of the Tennessee Williams adaptation. Playing opposite Paul Picerni would seem far less intimidating than scenery-chewing ordeals with Summer's Orson Welles, and Newman’s frankly more appealing with some of his intensity ramped down. Standing on tiptoes doesn’t necessarily enhance a star’s performance. The Young Philadelphians gives its supporting cast opportunity to rise to the occasion of meaty parts and show what they could do outside customary TV environs. Robert Vaughn was even nominated for an Academy Award here, having vaulted from Teenage Caveman rigors of only a year before. Barbara Rush and Brian Keith deserved higher profiles in features, though I wonder if the long-run money in prolific television work wasn’t actually better. Vincent Sherman brought tempo and variety to all such overheated mellers he directed --- I was reminded of his Ice Palace, The Hard Way, and The Damned Don’t Cry --- pictures like these can be mighty satisfying when executed by such a sure hand. There are many classics of a higher pedigree than The Young Philadelphians, but few you could spring on a general audience with as much assurance of positive feedback. By all means, try this one with your next movie gathering. Chances are they’ll thank you for it.

It’s quite a jump from all those resources at MGM’s disposal to the stripped-down economy of The Young Philadelphians, an otherwise tremendously enjoyable Warners melodrama just out on DVD. That title suggests a very specific background, but from the looks of things here, Warners might just as well have set it in Providence, Rhode Island, or Spartanburg, South Carolina. I hadn't the sense of even a second unit having gone to Philadelphia, let alone any of the principal cast venturing there. Warners spent $1.6 million on the negative. The picture doesn’t look cheap, but neither has it the care and production values that would have gone into something along the lines of Paramount’s Vertigo from the previous year, where the San Francisco setting was exploited to its full. Neither could it compete with your typical 20th Fox Cinemascope release, where backgrounds and art direction were vital elements of the whole. For all of that, I still prefer The Young Philadelphians over other selections in the Paul Newman DVD Collection. No other feature captures the Warner ethos quite so well, with its happy collision of up-and-coming stars (Paul Newman), eager beginners (Robert Vaughn, Adam West), and seasoned vets (Otto Kruger, Billie Burke, John Williams … that list is endless). Every time one of those balsa wood doors open, a welcome face emerges, and what inspired casting! Adam West as a Paul Bern-ish husband fleeing the marital bed, "Fred" Eisley just this side of Hawaiian Eye and vid greatness, Paul Picerni years before he’d become one of the most gracious of celebrities at autograph and collector shows. The Young Philadelphians is compulsive viewing. I’d challenge anyone not to like it, from inventive credits that reminded me of the later Ocean’s 11 to a climactic courtroom showdown pitting Newman against Richard Deacon. There’s something inherently pleasing about stories where nice guys are turned ruthless by experience and bitter circumstance. In this case, the worm turns early on and Paul Newman settles into what would become his dominant sixties persona. After prestigious turns in The Long, Hot Summer and Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, this had to have been regarded a comedown by the star. I suspect Paul thinks little more of The Young Philadelphians than he would of The Silver Chalice, yet he’s far more relaxed and natural here than amidst the lugubrious (and non-stop) confrontations of the Tennessee Williams adaptation. Playing opposite Paul Picerni would seem far less intimidating than scenery-chewing ordeals with Summer's Orson Welles, and Newman’s frankly more appealing with some of his intensity ramped down. Standing on tiptoes doesn’t necessarily enhance a star’s performance. The Young Philadelphians gives its supporting cast opportunity to rise to the occasion of meaty parts and show what they could do outside customary TV environs. Robert Vaughn was even nominated for an Academy Award here, having vaulted from Teenage Caveman rigors of only a year before. Barbara Rush and Brian Keith deserved higher profiles in features, though I wonder if the long-run money in prolific television work wasn’t actually better. Vincent Sherman brought tempo and variety to all such overheated mellers he directed --- I was reminded of his Ice Palace, The Hard Way, and The Damned Don’t Cry --- pictures like these can be mighty satisfying when executed by such a sure hand. There are many classics of a higher pedigree than The Young Philadelphians, but few you could spring on a general audience with as much assurance of positive feedback. By all means, try this one with your next movie gathering. Chances are they’ll thank you for it.

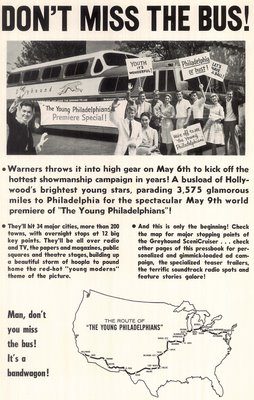

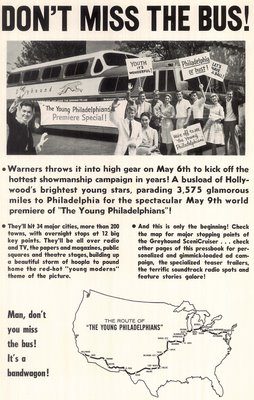

The Tall Target addressed a traumatic historical incident otherwise forgotten. So did The Young Philadelphians, only this one took place on a grueling cross-country publicity junket dubbed The Warner Transcontinental Star Parade by studio publicists. The idea was to load ten young contract players aboard a Greyhound "Scenicruiser" and transport them 3,475 miles from Burbank to Philadelphia, with stops in 27 cities and 200 towns. The bus would depart on May 6 and arrive at the premiere on May 19. At each stop, the players are instructed to pitch in wherever possible in granting interviews, posing for pictures, making theatre appearances, and, in general, creating good public relations for Hollywood as well as "The Young Philadelphians." The ten participants included Connie Stevens, Diane Jergens, Roger Smith, Alan Hale, Jr., Will Hutchins, Peter Brown, Jacqueline Beer, Troy Donahue, Ty Hardin, and Arlene Howell. Pounding home the red-hot young moderns theme of the picture from all those public squares and theatre stages had to be punishing work after sitting for hours aboard what I suspect was a sweltering bus (did Greyhound offer air-conditioning in 1959?) and traversing highways far less developed than those we enjoy today. Recalling my own family’s cross-country road trip to California in 1962, there were moments when it seemed we were pioneers in a covered wagon, such were travelling conditions in states like Arkansas and Oklahoma. For the modest wages these WB contractees were pulling down, this must have been akin to pulling oars in a ship’s galley. I’d love to hear from one of the survivors as to what they experienced.

The Tall Target addressed a traumatic historical incident otherwise forgotten. So did The Young Philadelphians, only this one took place on a grueling cross-country publicity junket dubbed The Warner Transcontinental Star Parade by studio publicists. The idea was to load ten young contract players aboard a Greyhound "Scenicruiser" and transport them 3,475 miles from Burbank to Philadelphia, with stops in 27 cities and 200 towns. The bus would depart on May 6 and arrive at the premiere on May 19. At each stop, the players are instructed to pitch in wherever possible in granting interviews, posing for pictures, making theatre appearances, and, in general, creating good public relations for Hollywood as well as "The Young Philadelphians." The ten participants included Connie Stevens, Diane Jergens, Roger Smith, Alan Hale, Jr., Will Hutchins, Peter Brown, Jacqueline Beer, Troy Donahue, Ty Hardin, and Arlene Howell. Pounding home the red-hot young moderns theme of the picture from all those public squares and theatre stages had to be punishing work after sitting for hours aboard what I suspect was a sweltering bus (did Greyhound offer air-conditioning in 1959?) and traversing highways far less developed than those we enjoy today. Recalling my own family’s cross-country road trip to California in 1962, there were moments when it seemed we were pioneers in a covered wagon, such were travelling conditions in states like Arkansas and Oklahoma. For the modest wages these WB contractees were pulling down, this must have been akin to pulling oars in a ship’s galley. I’d love to hear from one of the survivors as to what they experienced.